Many of us were around and involved in the firearms world to various degrees back in 1985, when Bill Ruger was developing his first centerfire autopistol, appropriately named the P85. Not actually widely available until 1987, it was a major step forward in Ruger history as the company continued on with its aggressive expansion into the handgun market beyond the single actions and rimfires that had made the brand such a familiar a name since 1949.

The P85 was a rugged double-action/single-action (DA/SA) semi-auto that offered very practical features, including a lightweight alloy frame, a high-capacity magazine and a choice of either a thumb safety or decocker, all at a very affordable price. Intended for military, police and recreational shooters, the pistol never gained U.S. military contracts or widespread police acceptance, but it did show up here and there in law enforcement leather, and the public at large gave it a good rating.

Design Evolution

The P89 was an upgraded, slightly lighter P85 with internal improvements, and the options were expanded to include a thumb safety, decocker or DAO system with no safety. Like the P85, the P89 used the same large and durable parts, with the same heavy investment in cast technology to keep costs down. The P89 was a relatively large and bulky pistol just like its predecessor, not to mention a fairly thick one.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Ruger’s first .45 ACP entry, the P90, was a scaled-up version of the familiar design adapted to a single-stack magazine. Still using the same production materials, technology and processes, it was still a thick pistol. Contributing to that thickness was the large protruding slide stop as well as the slide-mounted safety. Nobody considered the P85, P89 or P90 to be either slim or trim.

The introduction of the mid-sized P93 was an important evolutionary step in producing a markedly more compact 9mm pistol. With a shorter barrel and slide as well as an improved grip area thanks to its double-stack mag, the P93 exhibited more streamlined styling. The P94 that followed was fractionally longer but still much less blocky than the earlier designs, and the P94/P944 incorporated a new cam block that replaced the older Browning 1911-style swinging link. This cam has since been carried over throughout the Ruger centerfire pistol lineup.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The P95 was Ruger’s first “polymer pistol,” using the company’s nylon-reinforced version of a polymer frame. It was built along the same general lines of the P94 and was followed by the .45 ACP equivalent in the P97. Trimmer overall than the P85-derived models, and quite dependable, the two carried over the stick-out slide stop and safety levers.

The P345 in .45 ACP, the last of the P-series models in 2004, was another advancement intended to compete with features that were then popular in the market. It sported a very comfortable grip, less bulk, a flatter slide stop and safety, an internal key lock, a magazine disconnect and a loaded-chamber indicator on top of the slide. Much more modern in its approach, and more practical for concealed carry than earlier designs, it never quite took over the market share that Ruger had hoped for.

The SR series was introduced in 2007, beginning with the standard 9mm pistol, and has since superseded all previous centerfire pistol models in production. Much thinner, quite ergonomic and extremely concealable even in full-sized format, the striker-fired SR9 was another standout in Ruger evolution. The stainless slide combined with a nylon frame, a 17-round 9mm magazine (in the full-sized version), a low bore axis, a reversible backstrap, a very low-profile frame-mounted thumb safety instead of the slide-mounted safety on earlier models, and an equally low-profile slide lock. A Glock-style trigger safety, a cocked striker indicator, a magazine disconnect, an accessory rail and a loaded-chamber indicator added to the advances. The SR series has been a very successful line for Ruger.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

And then came the Ruger American Pistol in 2016.

Changing The Game

The reason we took a stroll down memory lane with Ruger’s pistol progression over the last 32 years is to show how it all began, what it went through along the way and where it is now. And where it is now is pretty damn good.

If you’re reading this, you probably saw the magazine articles reviewing the new Ruger American Pistol 9mm when the gun was introduced. If you’re a Ruger follower, you may have Googled 50 or so Internet discussions and videos where the first full-sized pistols were thrown against walls, frozen in ice, left in a pond overnight, run over by a Humvee and subjected to all sorts of unnatural abuses that have very little relevance to real life.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

With all the introductory dust settled, we decided to take another look with a slightly different approach. Few of us would allow our defensive tools to end up in a block of ice or at the bottom of a pond, but it just might be useful to know how that tool could hold up to several thousand rounds and an extended run without oiling or cleaning in a worst-case scenario. In other words: How does it function through neglect and high mileage should it ever have to? And, it might also be handy to know what you could expect in accuracy levels along the way.

The new Ruger American Pistol has everything it should have to be considered fully combat worthy. That means a very no-nonsense design that puts it squarely head to head against some of the best pistols out there. Ruger’s designers took features that were actually beneficial, jettisoned those that weren’t, did not pander to the nannies or stand on Ruger’s own older traditions and produced a tough product that’s built to kick some serious butt.

Although it was not submitted for the recent military trials that resulted in the nod going to the Sig Sauer P320, Ruger took the specs list required for entry into those trials as a baseline for building the new American. Why didn’t Ruger submit the gun? According to Ruger product manager Mark Gurney, “A good way to make a little money from federal government sales is to invest a lot of money.” Just to put the potential question of Ruger not believing its gun was “good enough” to rest for the doubters, Ruger decided the contract simply wasn’t worth the hoop-jumping it’d have to do, even beyond the design phase.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

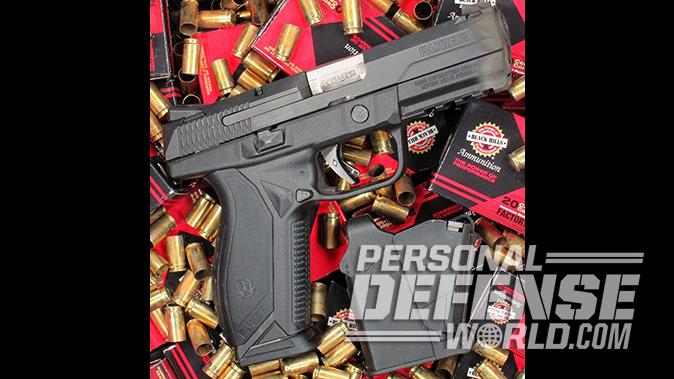

That said, this pistol was created to withstand the rigors of a military environment. The Pro Model configuration that I tested uses a black polymer frame with a modular, precision-machined stainless insert for rigidity (it’s the serialized part of the gun) under a through-hardened stainless slide with a black nitride finish. You’ll find steel Novak three-dot sights on top of the slide and a 4.2-inch, stainless steel barrel with broached six-groove rifling inside it along with a captive recoil spring. Unlike earlier Rugers, the loaded-chamber indicator is a small port at the rear of the barrel hood instead of a lever. The large ejection port pairs with a beefy extractor.

A new barrel cam design also increases the time the barrel and slide remain locked together on firing during the initial recoil impulse, allows for a lighter slide, and reduces the severity of the slide’s secondary return recoil impulse. This translates to less muzzle rise and faster recoveries.

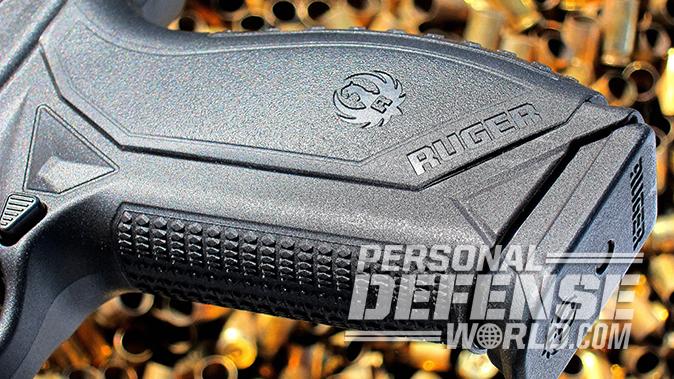

There’s no manual thumb safety on the Pro Model, but you’ll find a trigger safety as well as an internal firing pin block. The grip frame can be adjusted with three different-sized grip inserts, and the pistol comes with two nickel-Teflon-plated 17-round magazines. The steel magazine release is ambidextrous, while the takedown lever is mounted on the left side. Now for the slide lock.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The part that locks the slide open on a semi-auto is traditionally called a “slide lock,” “slide release” or “slide stop.” Its function under any of those names is to lock the slide back either automatically on the last shot fired or manually by hand. After that, the lever on many pistols also serves to unlock or release the slide so it goes into battery. Not here. Well, not on both sides anyway.

Army trial specs required a completely functional dual-sided slide lock that could also work as an ambidextrous slide release for those who use that method of running a slide forward on reloads. Ruger, not intending to submit for those trials and noticing a tendency for the slide to auto-close when a loaded mag was vigorously inserted, altered the dimensions to tighten up the lever so the pistol won’t let the slide go until you want it to go.

In the process, that left the right-side section unusable as a release. I can’t move it down on an open slide with both thumbs, yet the left side easily releases the slide. Important? To righties, no. To lefties who do plan to use it as a release, it’s a no-go. Most of us today either grip the slide from above or slingshot it anyway, so it’s just something to be aware of. The manual clearly labels it as a “slide lock,” which it does do manually on either side if needed, and recommends slingshotting the gun.

The Main Attraction

The friendly folks at Black Hills agreed to provide 5,000 rounds of their new 115-grain FMJ ammo for accuracy and reliability testing through a brand-new, full-sized American Pistol supplied by Ruger. That load, and five others, were fired through the pistol to measure its initial accuracy off the bench at an indoor range with static and repeatable lighting and air conditions. The remainder of the 10 cases of ammunition were fired elsewhere so I could lay out a ground sheet to make brass recovery easier on my back. After that, the same six loads were fired for accuracy again back at the same range.

Before the shooting commenced, I lubed the Ruger with Break Free CLP, and I decided not to re-lube or clean the pistol unless it started to malfunction. I also decided to use one magazine for all of the shooting unless it failed. I used an UpLULA loader to help reload the magazine. And since the Ruger’s mag gets progressively harder to fill beyond 10 rounds, each string would be a 10-rounder to save time and wear on my wrist.

Over five outdoor range sessions to blow through those 5,000 Black Hills FMJs—two of which consisting of 1,500 rounds each—the American operated flawlessly. This was despite temperatures ranging from 50 to 70 degrees, burning off any visible traces of lube early on, and never being cleaned at any point along the way. Bone dry for the last 4,000 rounds of outdoor shooting, with the slide heating up too much to handle with a bare hand on the longer sessions where I fired as fast as I could load and empty the mag, the pistol just would not quit.

As before, when I did a similar 5,000-round test of Ruger’s .38 LCR some time back, the American actually shot tighter groups afterward with four of the test loads. And that’s with a barrel still not cleaned after more than 5,300 rounds by then. That ending session did, finally, produce one single misfeed, where one lone G2 Research 92-grain Telos copper hollow point (CHP) hung up on the feed ramp. That particular load is a light one, figuratively and literally; it ejects brass roughly 8 inches straight up, with a low recoil impulse, and coupled with the sharp nose cavity edge and the slower slide return velocity, I can’t entirely blame the pistol for the glitch.

The Takeaway

It’s taken a long time for Ruger to arrive at a truly professional-grade centerfire pistol, but it finally has. The Ruger American Pistol is a modern combat gun for a modern combat role, and it delivers. Adding up 5,500 rounds all-in between two indoor and five outdoor sessions—running hot, dry, dirty and shooting with both hands, one hand, canted and even upside down—one malfunction with one light load among all that sells this pistol for me. Even aside from the accuracy, which is more than acceptable for its role.

The steel trigger and paddle transmitted some heat to my trigger finger on the 70-degree 1,000-round session, but not enough to be an issue, and I don’t foresee anybody else normally running these guns that hard. I did short-stroke the trigger reset six times—my fault entirely—and those were not listed as a malfunction for that reason. The OEM magazine sailed through all of the shooting intact, the slide never failed to lock open, and the trigger broke a shade on the heavy side at 6.75 pounds with some second-stage travel. The pistol is a fairly soft-shooter and easy to control. Ruger tested the American to 20,000 rounds without issues, and I would not have minded doing the same, but I think we’ve got a good enough picture here.

The Ruger American Pistol is a solid good-to-go value even at its MSRP of $579, and more so at an average street price of anywhere from $450 to $530 if you look around. And it’s well worth that look.

I’d like to thank Ruger for providing the American Pistol and Black Hills Ammunition for contributing 10 cases of ammo for this extensive shooting test. The project was informative for me, and I hope it was for you, too.

Ruger American Pistol Specs

| Caliber: 9mm |

| Barrel: 4.2 inches |

| OA Length: 7.5 inches |

| Weight: 30 ounces (empty) |

| Grip: Polymer |

| Sights: Novak LoMount Carry three-dot |

| Action: Striker-fired |

| Finish: Matte black |

| Capacity: 17+1 |

| MSRP: $579 |

Ruger American Pistol Performance

| Load | Starting Accuracy | Ending Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Aguila 115 FMJ 2.75 | 2.75 | 2.43 |

| Black Hills 115 FMJ | 2.81 | 3.06 |

| Black Hills 124 JHP | 3.38 | 2.43 |

| Federal 124 Hydra-Shok JHP | 3.00 | 2.56 |

| G2 Research 92 Telos CHP | 1.50 | 2.31 |

| Speer 147 Lawman TMJ | 3.00 | 2.69 |

*Bullet weight measured in grains. Velocity measured in fps by chronograph. Accuracy measured in inches for best five-shot groups at 25 yards.

For more information about the Ruger American Pistol, visit Ruger.com.

This article is from the January/February 2018 issue of “Combat Handguns” magazine. To order a copy and subscribe, visit outdoorgroupstore.com.