Ruger’s trim and handsome .44 Special Flattop Blackhawk is a near ideal combination of power and packability for the trail.

Nothing in the firearms world is more consistent than change and it is an interesting process to watch. Markets and manufacturing methods change, needs and tastes change, old favorites disappear and new favorites emerge. Change may not mean a positive one nor that new is better. But every now and then, something comes along that transcends the usual guerilla-marketing tactics.

Ruger teamed up with their largest distributor, Lipsey’s, to answer the long-running prayers of legions of die-hard .44 Specialites for a .44 Blackhawk that does not say magnum anywhere on it—the long overdue .44 Special Blackhawk is finally here.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Introduced around 1907 as an outgrowth of the older .44 Smith & Wesson Russian to provide more powder capacity, the .44 Special achieved a dedicated following beginning in the early days of smokeless powder big-bore handgun calibers that continued on in the hands of such notables as Elmer Keith and Skeeter Skelton. Skelton later wrote that he was so fond of the caliber that after WWII he sold his .38 Special and his saddle, quit smoking, cashed in his war bonds, bought a clean .38-40 Colt Peacemaker for $125 and sent it to the Christy Gun Works to be converted to .44 Special.

Introduced around 1907 as an outgrowth of the older .44 Smith & Wesson Russian to provide more powder capacity, the .44 Special achieved a dedicated following beginning in the early days of smokeless powder big-bore handgun calibers that continued on in the hands of such notables as Elmer Keith and Skeeter Skelton. Skelton later wrote that he was so fond of the caliber that after WWII he sold his .38 Special and his saddle, quit smoking, cashed in his war bonds, bought a clean .38-40 Colt Peacemaker for $125 and sent it to the Christy Gun Works to be converted to .44 Special.

He then had King’s Gunsight Company fit it with an adjustable rear and mirrored beaded ramp front sight, got a trigger job and a re-blue done elsewhere and added for a whopping $20 a one-piece ivory grip. While admitting that the round-nosed lead factory load running a 246-grain bullet at about 760 feet per second (fps) was “on par” with the .38 Special in effectiveness, he experimented with handloads in his Colt, eventually deciding that a 250-grain bullet loaded up to 1200 fps left the .357 Mag in the dust, and concluded that a cast-lead Keith semi-wadcutter dropped from a Lyman #429421 mould in front of 17.5 grains of 2400 powder and a CCI magnum primer would make a better manstopper than a .30-30 rifle. (Today, this load and a similar one also used by Keith would not be recommended in a .44 Special with the new and slightly hotter 2400 powder.) Skelton settled on 7.5 grains of Unique with a 250-grain Keith bullet as his working load. Incidentally, at the time of his death in 1988, he commissioned a Ruger Old Model Flattop Blackhawk conversion from .357 Mag to .44 Special. He felt it was a trim and reliable belt gun and a package worthy of the cartridge.

As anybody who can lay legitimate claim to being an old-timer in the revolver world knows, Keith felt too confined by the limitations of the Colt SA (single-action) in his big-bore endeavors. In 1927 he abandoned the .45 Colt and switched to the .44 Special large-framed, double-action S&W platform for his research that grew the .44 Special into the .44 Mag. Writing in 1936, Keith considered the .44 Special “our finest large-caliber revolver by a wide margin.” His preference for a powerful .44 continued on through into the .44 Rem Mag introduced in 1955.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Over the years, the .357 Mag and .44 Mag have come to largely overshadow the old .44 Special, and a number of different revolvers have been introduced and dropped from production. There was nothing special about the early factory loads, and the caliber traditionally had to be handloaded to make it earn its name. Commercial ammunition has caught up to a degree in terms of more modern bullet types and more realistic performance among some specialty makers, but it is not commonly stocked on gun shop shelves. The .44 Special has a dedicated fan base but it is not a mainstream number.

Although relatively small, there remains a market for a quality-made .44 Special revolver. Lipsey’s product development manager Jason Cloessner gambled on that market. Lipsey’s often contracts with the maker for low-number special runs of exclusives in variations that Ruger does not routinely catalog. When the mid-frame .357 Flattop Commemorative Blackhawk came out in 2005, along with updated production processes at the plant, it opened the door and it was not long before talks began about the possibility of a flattop in .44 Special.

It has always been possible to shoot Specials in any of the .44 Mag Blackhawks, but those are sizable pistols and the smaller frame makes for a more compact combination of power and weight. Production began in early 2009 with plans of 1,000 each of two-barrel lengths of 4.63 and 5.5 inches.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Gun Details

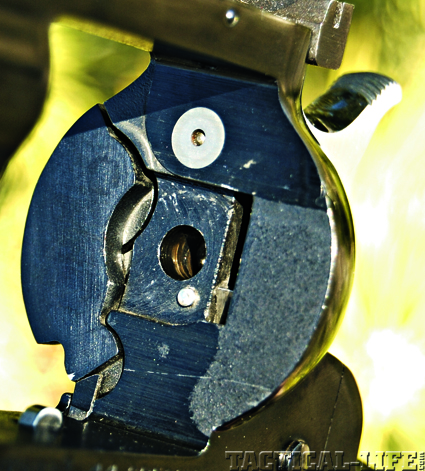

Recent reverse indexing pawl greatly speeds up loading and unloading of the Flattop.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

First off, you can expect quality. As a longtime carrier, both professionally and privately, I have a fondness for shorter tubes on working sixguns so the 4.63-inch barrel was requested. Ruger has never offered a high level of polish on blued Blackhawks, but this one has a uniform, deep and dark finish that sets it off nicely. The trigger and hammer side flats are left in the white, as usual. The pistol wears the black-checkered polymer grip panels that are now standard on most Ruger SAs since their longtime supplier of wood grips, Lett, closed up shop.

The fit between grip and main frame is very well done, partly due to the debate whether to use regular alloy grip frames and ejector housings, or to go all steel. Running at 70/30, steel won out, and steel grip frames are always fitted to the main frames whereas the alloy grip frames are not. This adds some poundage, which can be good or bad depending on your viewpoint. Aluminum totes lighter, steel reduces recoil in heavy loads. The extra weight is desired here.

Using the same frame and grip size as the New Vaquero, the .44 Special Flattop also shares the internal key lock and the same free-spin pawl lockup that aligns each chamber in position for loading easily in the frame’s gate cutout. But sights are a reversion to the older all-steel, fully adjustable Ruger Micro rear with its base fully inset into the flat topstrap. Regular alloy Blackhawk adjustable sights are fairly rugged, but steel is never a bad thing to have on a hardworking Ruger’s sights.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

There are two other points of interest on the .44 Special Flattop. As on all recent Ruger SAs the infamous warning is now on the bottom of the barrel next to the ejector rod housing where it is mostly out of sight and mind. Also, the cylinder base pin does not have the long-running flanged head with a crescent cutout that has to be aligned with the barrel when sliding it out or in to remove or replace the cylinder for cleaning.

The barrel warning bothers some more than others and may not be an issue for you, but the Colt-style cylinder pin is much handier than the older Ruger type. It can be removed entirely without also dismounting the ejector housing, unlike other short-barreled Ruger SAs.

Range Time

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Left to right: Black Hills 250gr Keith SWC, Buffalo Bore 185gr. JHP, Winchester 200gr Silvertip HP, Winchester 246gr RNL, Speer 200gr Gold Dot JHP, and Buffalo Bore 255gr Keith SWC. For non-reloaders, the Buffalo Bores are an excellent choice in hard-hitting commercial loads.

Handloading the .44 Special isn’t an option right now, so acquisition of five current factory loads ran from slow to wow for a trip to the gravel pit. To cover the spectrum, the classic Winchester 246-grain RNL was tested first, then their 200-grain Silvertip JHP, Speer’s 200-grain Gold Dot JHP, Buffalo Bore’s 185-grain JHP and 255-grain Keith LSWC. Last was a stash of Black Hills’ special run of 250-grain Keith LSWC loads that was offered for a short time back when S&W introduced their .44 Special Thunder Ranch Model.

As expected, the pedestrian 246-grain round nose was a pussycat in the 42.5-ounce Blackhawk, and the Buffalo Bore loads were both markedly stouter. Accuracy was about on par with my Ruger 50th Anniversary .44 Mag, which is largely what induced me to buy it and to buy this .44 Special when testing was over. The Ruger was controllable, and most empty brass dropped right out without using the rod.

The all-steel nature of this Flattop gives it a solid feel in the hand and helps mitigate recoil of heavier loads. Well balanced, it is still a SA and some noticeable muzzle rise will occur as it rolls back. But with these loads it was far less than a comparably barreled .44 Mag or hot-loaded .45 Colt. Trigger pull was a slightly creepy 4.75 pounds and the hammer was not oversprung as Ruger SAs tended to be for several years. Loading is easier with the reversing index pawl than with older models with fewer tendencies to over-rotate past the gate channel.

The classic 246-grain lead was very tolerable as an occasional foray into nostalgia, for more serious uses the Winchester and Speer HPs provided mid-level performance along with mid-level recoil. The two specialty loads step things up another notch at both ends of the barrel.

One complaint I have across the board in the current big-bore Ruger thumb busters that use the checkered polymer grip panels is that they are sturdy but the checkering on those things can bite with loads that produce big-time recoil. The .44 Flattop was tolerable up to and including the Buffalo Bores, but I prefer a smooth grip. Ruger carries rosewood panels with the older black eagle logo medallions to fit the Blackhawk’s smaller grip frame for $44. If you plan to be using this .44 as your main mammoth medicine, they would be a good investment.