At concealed carry classes and on the internet, I run across many armed citizens who seem to believe that their “rules of engagement” are totally different from those of police. Yes, there are some differences. The officer acting on behalf of a government entity may have elements of qualified immunity and sovereign immunity that the individual citizen would not, but the officer also has burdens the citizen doesn’t have. The officer may be forced to answer questions or be fired, under the Garrity precedent. The citizen needs to worry about criminal and civil court aftermaths, but the officer has to worry about that and a Federal 42 USC 1983 action alleging that he or she acted under color of law to deprive the man they shot of his rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of killing cops.

When it gets right down to the nuts and bolts of when you can and can’t pull the trigger, there are far more similarities than differences between the rules for “civilians” and the rules for police. This is why there is so much an armed citizen can learn from police training in this area. I was reminded of this recently while teaching at a police seminar.

Founded by legendary police trainer Ed Nowicki and led today by retired police chief Harvey Hedden, the International Law Enforcement Educators and Trainers Association (ILEETA) is unique among criminal justice organizations. ILEETA celebrated its 10th year in existence at its annual conference, which took place in Wheeling, Illinois in April of 2013. Well over 700 police instructors were in attendance.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Membership, and attendance, is open only to those who train law enforcement or corrections personnel. (Yes, there are some “civilians” among that group.) Programs are geared toward “training the trainers,” who transmit the lifesaving lessons to their own agencies. A broad spectrum of skills and specialties is always on the curriculum. There are many courses in firearms, and on self-defense with deadly weapons, intermediate force tools and bare hands. Let’s look at some of the lessons presented at ILEETA and how they might apply to law-abiding private citizens who used guns in self-defense.

STOPPING MASS MURDERERS

Just before the seminar kicked off, Case One occurred in Texas, in which a man with a carpet-cutter and an admitted obsession with killing people slashed 14 victims on a college campus. Interestingly enough, students stopped him by tackling and overpowering him before police could get to the scene.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The horror of Case Two was still fresh in the minds of all present, the horrific murder of 20 children and six adults at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, four months prior to the conference. In the many training sessions that week which encompassed responding to such incidents, some instructors noted that armed citizens had been known to stop mass murders. In Case Three in Pennsylvania, a psycho teen’s killing rampage amidst a school function at a restaurant facility ended when the restaurant owner took him at gunpoint. In Case Four in Mississippi, another teen murderer surrendered when the vice principal of the school he’d shot up leveled a Colt .45 auto at him.

In Case Five in Virginia, two law school students captured at gunpoint a criminal who had shot six people at the institution, killing three. Though they turned out to be off-duty police officers, they were not at the school in that capacity and essentially had one foot in each world at the time of their courageous action. Case Six occurred in Oregon in roughly the same timeframe as the Sandy Hook atrocity. A gunman opened fire in a shopping mall. As soon as he saw a private citizen with a concealed-carry permit pointing a Glock .40 at him, the criminal turned and fled, and then ended his own rampage by killing himself.

None of those rescuers got into any trouble for their actions. Cop or civilian, they stood on firm legal grounds. All took the actions they did for the same reasons. These incidents were used in police response discussions to point out that one or two armed responders at the scene are often enough to stop the killing and save countless lives.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

ACTION VS. REACTION

Retired career cop Brian McKenna is one of the world’s leading authorities on analysis of gunfights. He made the point that an officer has to know when he’s justified in using deadly force, or he’ll hesitate when he needs to do it. He made the point with Case Seven, when murdered a deputy a gunman in front of his own patrol car’s dash cam. Fellow officers who knew the deceased said he was leery of using force because he had been chastised for doing so in the past. When the time came to act or die, he visibly hesitated and paid for it with his life. This sort of thing is as familiar to a CCW instructor in the private sector as it is to any police trainer. McKenna contrasted that with Case Eight, in which a city police officer faced a suspect believed to have killed four cops. On high alert, this officer did not hesitate when the opponent went for his gun, which turned out to have been stolen from the body of one of his victims. This officer knew what he had to do, and did it instantly: He shot down the cop-killer in a fatal hail of .40-caliber Gold Dot bullets.

The lawmen in Cases Seven and Eight were both known to be skilled shooters. They were armed with identical service pistols, Glock 22s. The difference was that one hesitated, perhaps uncertain as to how far he could go. He died on scene. The other officer was confident in his knowledge of justifiable use of deadly force, and because he didn’t hesitate, acted in time to save his own life. If you take way the badges and uniforms and replace them with CCW permits and sport coats, is there really any difference?

DELICATE BALANCE

We all see the truth in the old adage that he who hesitates is lost, and in the motto of Britain’s elite Special Air Service (SAS), “Who dares, wins.” At the same time we have to remember that the SAS is deeply trained in rules of engagement. The trick is to find the delicate balance of knowing beforehand exactly how much force is called for and exactly when gunfire is justified. Society demands armed citizens and peace officers alike to be in the right when they pull the trigger.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

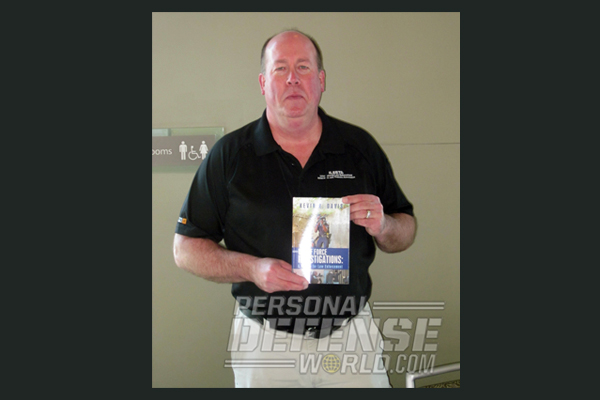

An excellent new book gives great insight into finding that balance. The title is Use of Force Investigations: A Manual for Law Enforcement by Kevin R. Davis, a veteran SWAT cop, experienced expert witness and master use-of-force instructor, wrote it. Available in both print copy and Kindle editions from Amazon, Davis’ book breaks many “media myths” and public misconceptions, and delivers a solid grounding in use-of-force principles, up to and including the use of lethal force. Filled with examples from actual cases, I believe it will be every bit as valuable to law-abiding armed citizens as it has already proven itself to be for working law enforcement personnel—and for the supervisors and trainers who must speak for them in court after the fact.

The cop and the citizen share a common enemy: the violent criminals who prey on the public. There is much that the ordinary person who lawfully carries a gun, or keeps one at home or at work for defensive purposes, can learn from police and the people who train them and their instructors.

Check out this article about Self-Defense and the Law: Perceptions When Women Use Deadly Force.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below