To describe something as the best is to say it is unequivocally better than the rest. It’s a bold statement that I don’t make cavalierly. Today, the semi-auto pistol dominates the self-defense market and snub nose revolvers don’t get as much attention.

I am not arguing that the revolver is superior to the autoloader for self-defense; that is a personal decision. However, there are two families of snub-nose revolvers whose excellent design, ergonomics, strength, workmanship and power-to-size ratio have convinced generations of people to bet their lives on them. Those families are the Colt Detective Special, produced from 1927 to 1986, and the Smith & Wesson Chief’s Special, introduced in 1950 and still in production today. If you are considering a snub nose revolver for concealed carry, shooting these pistols will be a useful educational experience. They are the benchmarks by which all others are judged.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Colt Police Positive

Colt pioneered the revolver, and by the 1890s, it was perfecting the swing-out cylinder and its own double action. Smith & Wesson was doing the same. Colt’s .38s got the military contracts, but in 1898, S&W introduced a more powerful .38-caliber cartridge. The .38 Special was an immediate success and remains one of the most popular handgun calibers in the world.

The Colt Detective Special and its common siblings, the Cobra and Agent, are all basically Colt Police Positive Special revolvers with 2-inch barrels. By 1908, when Colt introduced the Police Positive Special in .38 Special, it was the most compact double-action .38 Special revolver with a swing-out cylinder in the world. Its small size and weight, combined with its strength and the power of the new .38 Special cartridge, made it extremely popular with police and civilians. Its grip size was manageable for small and large hands alike.

The Police Positive Special was the sleekest and most graceful double-action Colt ever made. It had better-than-average fixed sights for the time, pointed well and allowed accurate double- and single-action firing.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Going Undercover

It wasn’t until 1927 that Colt introduced a 2-inch-barreled version called the Detective Special. The company marketed these snub nose revolvers specifically for plainclothes law enforcement officers needing a more concealable handgun. From 1927 until 1973, the Detective Special loaded the most firepower into the smallest package that you could buy. (In 1973, Charter Arms introduced its Bulldog series of five-shot .357 Magnum and .44 Special snub noses that were comparable to the Colt in size, but not in quality or strength.)

The Detective Special was 6.75 inches long and weighed 21 ounces. Like the Police Positive Special, this Colt held six shots and featured a Positive Lock internal-hammer block safety. This prevented an unintentional discharge if it was dropped. It was a huge success and set the standard for what a concealed-carry revolver should be. During the 61 years it was in production, it was modified only slightly.

Changing Up the Detective Special

After 1947, notable changes to the Detective Special included a longer ejector rod and altered grip frame. Additionally, Colt switched the front sight from a round half-moon to one with a little ramp cut on the back. The grip frames on these post-1947 guns were a little roomier behind the triggerguard and considerably shorter. The grips themselves though were virtually the same size as the earlier guns.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

In 1950, Colt introduced the Cobra, an aluminum-framed clone of the Detective Special that weighed only 15 ounces. The less expensive, and less finely polished, Agent followed in 1962. In 1973, Colt made the barrel heavier and included an ejector rod shroud and a ramped front sight that ran the full length of the barrel.

Then, in 1986, production of the Detective Special and its D-frame variants ceased due to flagging sales resulting from the rising popularity of 9mm semi-autos in the American market. A short run of Detective Specials was made from leftover parts in the mid-1990s, but thereafter, Colt seemed determined to abandon the venerable design in favor of something new. The SF-VI and DS-II snub nose revolvers retained the look and feel of the 1970s Detective Specials, but in stainless steel and significantly re-engineered for economy. Production of these models did not extend beyond the late 1990s. At present, shooter can only find these snub nose revolvers on the used/collector market.

Hail To The Chiefs

Colt had a virtual lock on the top end of the snub nose revolver market until 1950, when S&W created an even more compact .38 Special revolver. Smith first introduced the gun at the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) conference, where a contest was held to name the new handgun. Of course, the chiefs named it the Chief’s Special.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

After 1957, S&W started using numerical designations, and the Chief’s Special was renamed the Model 36. The model numbers are very helpful, since S&W had far more variations of the Chief’s Special than Colt ever had of its Detective Special.

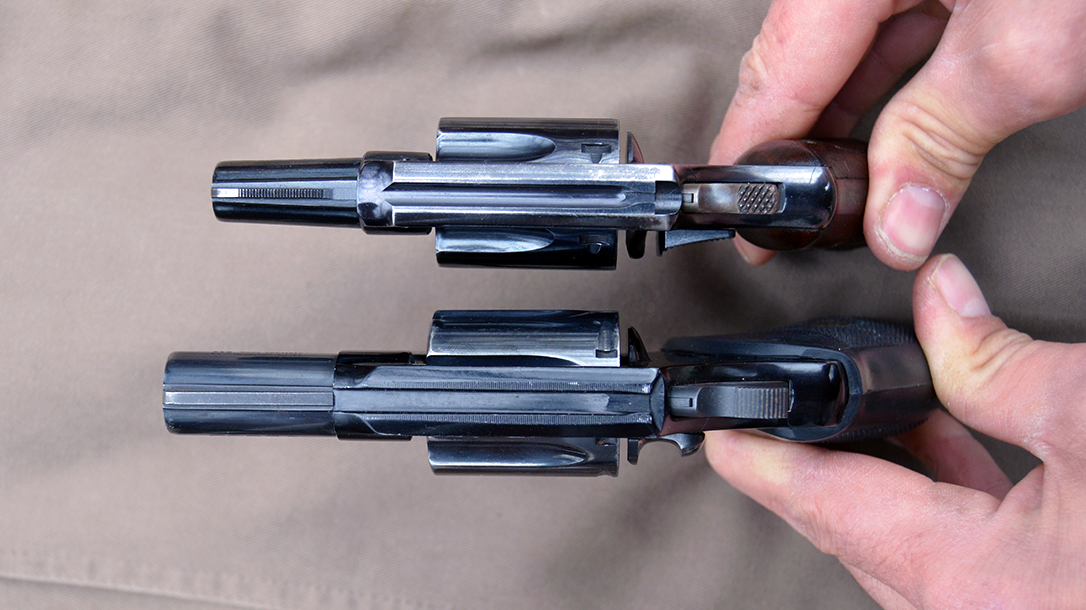

To make the Chief’s Special, S&W beefed up its venerable 19th century I-Frame into the slightly larger J-Frame. Engineers also slimmed the revolver down by using a five-shot cylinder. The gun measured only 6.5 inches long with a 1.87-inch barrel and weighed just 19 ounces in steel. It had fixed sights and a grip frame about 20-percent smaller than the Colt Detective Special. This made it easier to slip into a pants or coat pocket. Well made with a stronger lockup than a Colt and an exceptionally good shooter, the Chief’s Special was immediately popular. Colt now had a real challenger in the marketplace.

Airweight Snub Nose Revolvers

In 1951, S&W made an aluminum-framed version called the Chief’s Special Airweight. The company later named it the Model 37. Like Colt, it tried and failed with aluminum cylinders (they eventually cracked) before turning back to steel. Still, the gun weighed only 14 ounces, and S&W’s Airweights are very popular concealed-carry guns to this day. The downside is there’s more felt recoil, which can make extended range sessions unpleasant.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

In 1952, on the 100th anniversary of Smith & Wesson, the Chief’s Special’s hammer was cut down and the frame modified to completely enclose it. The resulting double-action-only revolver was exceptionally graceful and compact. It offered a snag-free draw from the pocket. Also, shooters could actually fire reliably from inside a pocket. A grip safety was added but eventually dropped. S&W named the new pistol the Centennial, but changed it to the Model 40 in steel and Model 42 in Airweight form.

The Greatest?

In 1955, S&W introduced the Bodyguard, arguably the best concealed-carry revolver of all time. It appeared first as an Airweight (Model 38), then in steel (Model 49) in 1959 and later stainless steel (Model 649). The Bodyguard was a Chief’s Special with the rear frame raised to enshroud all but the grooved top of the hammer. With virtually no exposed hammer, the Bodyguard had the perks of the Centennial, with the addition of manual cocking for single-action shooting.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Colt never made a concealed-hammer Detective Special, but did offer a flip-up hammer shroud accessory. However, its installation required gunsmithing skill. The shroud was in high demand by policemen who carried the Colt for undercover work.

Going Stainless

In 1965, S&W broke new ground for the firearms industry when it offered the Chief’s Special in stainless steel. The company designated it the Model 60. Also, it was the first stainless steel production firearm ever made. S&W soon followed with stainless steel versions of all its steel J-Frames, generally adding a “6” in front of the old model number. For example, the Model 49 Bodyguard became the Model 649 in stainless steel.

Detective and Chief’s Specials are high-quality, accurate, durable snub nose revolvers. The aluminum-framed models were not intended for +P ammunition, but the steel-framed guns will handle it. Modern .38 Special +P loads appear to be comparable to standard loads used prior to the 1970s. If you look at the 1940 catalog entry for the Detective Special, it states that the revolver will handle the .38 to .44 Special. That cartridge was a precursor of the .357 Magnum and pushed a 158-grain jacketed bullet to over 1,000 fps. Of course, a steady diet of hotter ammo is likely to accelerate wear and give your hand a beating. Also, bear in mind that you can never be sure what type of abuse an old gun has endured before you got it. That being said, it’s common to practice with standard loads and save the +P for concealed carry.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Personally, I prefer the even trigger pull of the S&W J-Frames. The Colt trigger is nice, too, but it stacks toward the end of the pull. I also prefer a heavier steel gun to the alloy Airweights, as I find it easier to get back on target between shots in rapid fire. I also figure its makes a better club should I expend my fifth round and fail to execute my exit strategy.

Still Going Strong

I have known many policemen who chose Detective Specials over Chief’s Specials because the Colt had six shots to S&W’s five. The owner of Sportsmans Rod & Gun in Elizabethtown, Ky., chose the Colt Cobra for the same reason. Later, he retired it in favor of a compact 9mm semi-auto because it was thinner and had more shots. His store is one of the best and largest in the state, and he sells a lot of concealed-carry firearms. He told me that revolvers take second place to autoloaders. However, modern S&W J-Frames still dominate snub nose revolvers. They are the most expensive of their peers and still the best sellers. That should tell you something.

It takes a lot more practice to shoot a revolver well than it does an autoloader. However, in my experience, mastering that double-action trigger pull made me a much better marksman overall. I am a simple guy, and revolvers are pretty simple. Aim and pull the trigger and they go bang.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

If they misfire, you just pull the trigger again. I don’t have to defend my gun shop or chase down felons, so I’m sticking with the five-shot S&W Model 649 clipped onto my belt or slipped into my pants pocket. I hate to sound like a curmudgeon, but in my observation, new is not always better. And for my purposes, the compactness, reliability, power and shootability of this 60-year-old design cannot be beat. I have a feeling that a great many vintage Colt and S&W snub nose revolvers are still about town, discreetly, in a great many pockets.

This article was originally published in Concealed Carry Handguns 2019. To order a copy, please visit outdoorgroupstore.com.