The operation that came to be known as the Bay of Pigs—taken from the marshy area where the mission began and pretty much ended—may have been the most ill-considered special operation ever attempted under the aegis of the United States. The idea of an invasion to remove Fidel Castro from power in Cuba was conceived and approved—but never fully executed—by the Eisenhower administration, which was terrified by the prospect of a Communist regime just 90 miles off the tip of Florida. In 1959, with the pressure of the Cold War ratcheting up to almost unbearable levels and much of the American public—their fears stoked by demagogues like Joseph McCarthy—looking for Communists around every corner, it’s no surprise that Castro’s rise to power right next door would cause such alarm.

- RELATED STORY: 8 Rimfire Replicas of History’s Greatest Battle Weapons

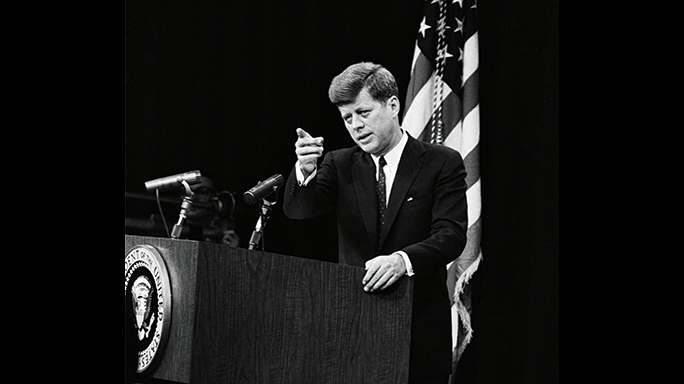

The plan was a simple one: The CIA would raise an anti-Castro military force from the rabidly anti-Communist Cuban population in the United States, then lead them on an invasion of Cuba supported by American airpower that would rapidly be hailed by the people of Cuba as well as a segment of the Cuban military, who would join their liberators in throwing off the yoke of Communism under Castro. The Kennedy administration, just as concerned about Castro as the Eisenhower people were, gave the green light for the operation in 1961.

- RELATED STORY: Spec-Ops: A History of the US Special Forces

Unfortunately, almost every element of the mission was botched. First, by the time the invasion took place, it was a very poorly guarded secret, as the Cubans recruited for the effort, who had been training in Guatemala since March 1960, spread the word throughout their community and beyond. Castro was well aware of it. Second, the American bombers that were supposed to cripple Cuba’s air force were obsolete World War II B-26 aircraft that missed most of their targets. (American involvement in the operation was further confirmed when some of the planes were shot down and photographs of the repainted American planes became public.) Third, intelligence suggesting that the public would greet the invaders as liberators vastly underestimated Castro’s popularity as well as the enmity felt by Cubans for the American government, which they associated with the corruption and excesses of Cuba’s previous governments. (Kennedy was desperate to keep America’s role secret but failed to do so.) Finally, the policymakers woefully misjudged the military situation: The force of 1,400 Cuban exiles, led by some 125 CIA operatives, came under immediate and heavy fire, American air support was insufficient to say the least, and two of their escort ships were sunk by Cuban planes. Within 24 hours, the invading forces were overwhelmed in every sense by 20,000 Cuban troops, who completely quashed the rebellion before it even got started. (There was no evidence of any defections at all from the Cuban military.) Some 1,200 soldiers from the invading force were captured and more than 100 were killed. Acknowledged casualties among the Americans included four airmen and one paratrooper. There were 176 deaths among the Cuban forces.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

- RELATED STORY: Operation Red Wings | Navy SEALs & Army Special Forces

The lessons of the Bay of Pigs were clear: Never let your ideology blind you to the facts on the ground and never put lives at risk without reliable and well-sourced intelligence. American special ops moving forward were not universally successful, but none were undertaken without heeding these critical lessons.