Springfield’s Loaded Parkerized 1911-A1 carries custom touches, a no-snag design, and eight rounds of .45 ACP power to any callout.

Springfield Armory and I go back a long way. Not as far back as 1974, which is when Springfield was “reborn” in Geneseo, Illinois, but at least as far as 1986, when my wife placed a plain-vanilla, mil-spec, olive drab 1911 underneath the Christmas tree. I replaced the miniscule sights with ones I could actually see, then spent the next 15 years or so trying to wear the gun out or make it fail to feed, fire or eject. It was a workhorse, an absolutely reliable companion. The 1911 clearly has a strong tradition as a military pistol due these very characteristics, but in its enhanced versions, it can also serve capably as a specialized LE tactical pistol. An excellent example of this is the Springfield Loaded 1911-A1, a sample of which recently showed up at Abbott’s Farm Supply in Halifax, Virginia, for me to test out. As I opened the case, I remember thinking to myself, “This one may be hard to send back.”

The low-profile, Novak-style rear sight is snag-free and adjustable for windage. It has tritium inserts for low-light situations.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Gun Details

The Springfield Loaded Parkerized 1911-A1, model number PX9109LP, is a solid, robust, full-sized .45 with lots of semi-custom refinements. The Parkerized finish is a dull black, and the best way to describe the look of the gun is to say it’s all business. This pistol features a 5-inch, stainless steel barrel, forged frame and slide (precision-fitted), front and rear cocking serrations, and a flat mainspring housing. The gun has no sharp edges—Springfield calls this the “carry bevel” treatment—and it wears dovetail-mounted front and rear sights. The rear sight is the low, swept-back “Novak” style, and both front and rear sights have tritium inserts. The beavertail grip safety has a small “speed bump” and the hammer is the somewhat elongated, spurless version that Springfield designates a “Delta lightweight hammer.” No danger of getting the web of your shooting hand pinched here.

The grip panels are very attractive cocobolo hardwood, nicely checkered and bearing the Springfield Crossed Cannons emblem. The ejection port is lowered and flared, and the magazine well is very slightly beveled. The long, aluminum, match-grade trigger is advertised as breaking at 5 to 6 pounds. Mine broke at 5.25 pounds when I first weighed it, but it was so crisp that I would have guessed it was much lighter. After a few hundred rounds and a thorough cleaning, the trigger got even better, dropping the hammer at exactly 4.75 pounds. It has stayed at that weight ever since.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The ambidextrous thumb safety is slightly elongated and serrated. The recoil system uses a two-piece guide rod—something with which I had no experience, and something I thought might take some getting used to. While John Browning did not design the 1911 with a full-length guide rod, folks have been experimenting with it and arguing hotly about its advantages and disadvantages for some time now. With the introduction of the two-piece rod, there is even more to argue about. A full-length guide rod may aid in accuracy and smoothness of function, as some competitive shooters believe. But it also makes disassembly and reassembly a little more complicated. A two-piece full-length guide rod is a bit easier, but it requires an Allen wrench.

In fact, all three guide rod systems (including the traditional GI) seem to work just fine, and each has its adherents and detractors. Once I got used to it, I found the two-piece system easy to work with. For what it’s worth, the new Springfield has an extraordinarily smooth action, and it works just fine. If I keep the gun, I’ll keep the two-piece guide rod.

Inside the sturdy plastic case I found a polymer holster and double magazine pouch, two of Springfield’s seven-round magazines, a cleaning brush, an instruction manual, and a sheet of coupons for discounts on other merchandise from the company. There were also a couple of keys for the Internal Locking System (which is designed to lock the action of the pistol so that it cannot be fired), one Allen wrench for taking out the two-piece guide rod, and another smaller Allen wrench for adjusting the sights. Mine needed no adjustment at all. Finally, there was a curious little L-shaped tool for removing the mainspring housing in case one should desire to do so.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

This is a big, beefy handgun weighing exactly 40 ounces with an empty magazine inserted. That’s a few ounces heavier than some of John M. Browning’s variants, but the gun balances so well in the hand and rides so well in its polymer holster that the difference is not really noticeable.

Check out this article about Ballistic’s Best Full-Size Handguns!

The lightweight aluminum trigger broke crisply at 4.75 pounds and, paired with the excellent sights, made the 1911-A1 very accurate.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Range Time

My range time with the new Springfield was spread over several days and eventually gobbled up about 600 rounds of ammunition of various types and from several different manufacturers. The first day was a hot and humid one in southeastern North Carolina, and a couple of hours on the shade-free range gave me all the fun I could stand, even with someone else’s pistol to play with. Still, it offered a good opportunity to give the gun an initial test.

The first thing I noticed was that the sights were set perfectly for me, and I didn’t have to touch the little Allen wrench to drift the rear sight left or right, nor did I have to guess at elevation. This doesn’t always happen with out-of-the-box sights. I found myself wishing that the rear sight notch had been just a little wider, as there was very little “air” between the outer edges of the front sight and the inner edges of the rear. Someone with younger eyes might have no problem with this, but I like seeing a little more daylight around the front sight.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The gun ran reliably after an initial break-in period of 300 rounds, plus a thorough cleaning. After that, I went through another 300-plus rounds from various manufacturers and the pistol showed no flaws. Recoil was negligible, as one would expect for a full-sized 1911. The smooth, rounded contours, the beavertail safety, and the delta hammer all combined to make an extended range session pleasant and comfortable. This is a very tight gun, with no sloppiness or play anywhere in the slide-to-frame fit, and it is also buttery smooth. Another advantage of a gun weighing 40 ounces is that the sights barely lift off the target in rapid fire. Quick follow-up shots are a lot easier with this gun than with my Combat Commander.

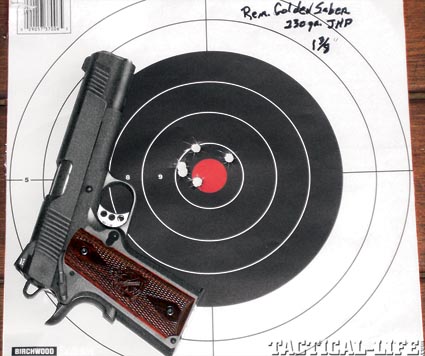

I did the accuracy testing at 25 yards, seated, using a sandbag rest on a wooden bench. The average for all the five-shot groups, using a wide variety of ammunition, was a little less than 2.5 inches. Keep in mind that those are groups fired off a sandbag, not out of a mechanical rest. There were many times when I had four shots in an area of 1.5 inches or slightly more, only to have the fifth shot stretch the group a bit. The best average (2.2 inches) came from Remington’s 230-grain Golden Saber HPs, followed closely by Winchester’s 230-grain PDX1 ammo. This is a very potent self-defense load, with an advertised muzzle velocity of 920 feet per second (fps), 432 foot-pounds of energy, and a bonded hollow point that duplicates the performance of the old “Black Talon” without looking so politically incorrect. The Golden Sabers also gave the best individual group, putting everything into a tight, 1.38-inch cluster.

Finally, of all the ammunition tested, including the perfectly ordinary stuff you can pick up at your local discount house, nothing produced a spread of more than 3 inches for the average of five shots. Obviously, this Springfield will shoot a tight group with almost anything you can find to feed it.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Final Thoughts

Having spent several weeks with the new Springfield, I found it to be a finely crafted handgun with rugged, no-nonsense good looks, excellent ergonomics, and very impressive accuracy. It’s not a full-custom pistol, but it has most of the added features that one would expect in a custom gun, and its suggested retail price is about half what one might pay for a custom-crafted handgun built to one’s personal specifications. The low-mounted sights with tritium inserts are easy to see in any light and snag-free, the trigger is perfect for a duty handgun, and the checkered backstrap affords a sure grip. The black Parkerized finish is not only distinctive looking on this pistol, but it also is much tougher and more wear-resistant than many finishes. This is a pistol that could serve admirably in the hands of an LEO—it is a solid, practical version of the classic 1911 with enough custom touches to satisfy anyone.