The Vietnam War was the first jungle conflict fought by the U.S. armed forces since World War II in the Pacific. As a result, there had been little acquisition of new shotguns during the intervening 20 years.

- RELATED STORY: Stevens 320 Pump Security 12 Gauge Shotgun

The U.S. Army and U.S. Marine Corps entered the Vietnam conflict with the same shotguns that had seen service in World War II—the Winchester Model 12, the Winchester Model 97, the Stevens 520-30 and the Stevens 620A trench and riot guns. Many had been arsenal refurbished after World War II. Most popular was the Model 12 Winchester, especially with the Marines. Some other riot guns were acquired for issuance to the Vietnamese, including the Ithaca Model 37. Additionally, some Ithaca Model 37 riot guns and a few trench models were acquired by the U.S. Navy for use by riverine forces and SEALs.

Battlefield 12 Gauge

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Early in the Vietnam War, the Stevens Arms Company received orders for military Model 77E riot guns. They saw wide usage in Vietnam, especially among MPs, though with infantry and other units as well. Some also went to the Vietnamese. Reportedly, 60,920 Model 77E riot guns were delivered to the U.S. Armed Forces or allies beginning in 1963. According to U.S. military shotgun collector Jeff Moeller, factory records indicate 77E production ended in early 1964, rather than later as is sometimes cited. The first delivery of the initial contract took place on May 24, 1963 and the last on December 31, 1963 for a total of 58,940. A supplemental contact resulted in the delivery of 1,980 on February 14, 1964.

Four companies bid for the contract, with Savage Stevens being the lowest at $31.50 per shotgun, followed by High Standard at $33.25, Ithaca at $38.11 and Remington at $55.43. Stevens was actually overbid on the shotguns, as their actual charge to the government was $33.51 each. The contract also included a cleaning rod to be supplied with each shotgun. To illustrate how closely Stevens watched their costs, the rubber recoil pads were produced by Ohio Rubber Company and have distinctive “T” cutouts, as this saved one cent per recoil pad over a solid rubber pad.

One advantage of the 77E was that it was inexpensive. Because the original intent was to provide the 77E for Vietnamese forces, the stocks were reduced by about 0.62 inches, making length of pull 13 inches. Fortuitously, this allowed U.S. troops to use them readily while wearing flak jackets, but, in general, U.S. troops did not like the shorter stock. Unlike most U.S. GI shotguns, the 77E was fitted with a thick recoil pad. This was in deference to the smaller Vietnamese as well. In combat, the stock proved the weakest part of the 77E, especially if used to butt-stroke an enemy. As a result, armorers often had to replace stocks. This problem also resulted in a large number of spare stocks being produced with recoil pads.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Some of these replacement stocks were longer than the originals, probably because repairs were being made for U.S. units with U.S.-sized troops. For years after the Vietnam War ended, these stocks were common on the surplus market, but they have gotten much scarcer now, as I learned when I was searching recently for one for my 77E. Another problem mentioned by armorers occurred with the triggerguard, which was made of alloy and often broke. Apparently, however, there were no replacement triggerguards available in the supply system. Overall, compared to the Model 12 Winchester or the Ithaca Model 37, the 77E was not considered as sturdy for combat, though it saw quite a bit.

Into The Action

Martial 77E shotguns are readily identifiable by the Parkerized receiver and barrel; the “U.S.” stamped on the right side of the receiver just behind the barrel; the “P” proof marks on top of the receiver and barrel; a 20-inch, cylinder-bored barrel with a bead sight; a black, stained stock and forearm; a rubber recoil pad; and sling swivels. Often, Vietnam 77Es will be encountered with most of the black stain worn off of the stock and forearm. Note also that there were two types of front sling swivels—either attached to a barrel band (earlier type) or attached to the magazine plug platform. Reportedly, a few 77Es were fitted experimentally with bayonet adaptors, though it does not appear any were actually issued to troops. There may have been some 77Es that had bayonet lugs added by the Vietnamese.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The 77E riot guns had a trigger disconnect, which meant that unlike the Ithaca 37s in use by the SEALs, the trigger could not be held back while the slide action was cycled to fire rounds quickly. Still, the 77E could be fired very quickly, and users learned to feed additional shells whenever there was a lull in the fighting. In fact, one study showed that the shotgun had a higher kill ratio than the M16. Arguably, the fact that the shotgun was normally used at closer range may have contributed to this. The 77E had a cross-bolt safety at the rear of the triggerguard and a slide/bolt release on the left side in front of the triggerguard. This location was actually more ergonomic than the location of the slide/bolt release on many other combat shotguns.

Though originally intended primarily for the Vietnamese, the need for shotguns by U.S. troops resulted in thousands being issued. As mentioned earlier, the 77E saw a lot of service with U.S. Army MPs. Those assigned to convoy duty often carried the Stevens, as did those assigned to guard communist prisoners, HQs or other installations. Some patrol MPs in Saigon and elsewhere also carried the 77E.

During the Tet Offensive, the 77E and other shotguns would have been invaluable in clearing VC from buildings. At least some Army and USMC infantrymen assigned to point duty carried the 77E, and the 77E and other shotguns were used for clearing VC bunkers or tunnels, though most tunnels were so constricted that only handguns could be used. Both MPs and other dog handlers used the 77E as an alternative to the M16 or, later, the XM177. The 77E or other shotguns would have been most useful on convoy duty when moving through villages or other areas where an attack might be launched at close range.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Combat Loads

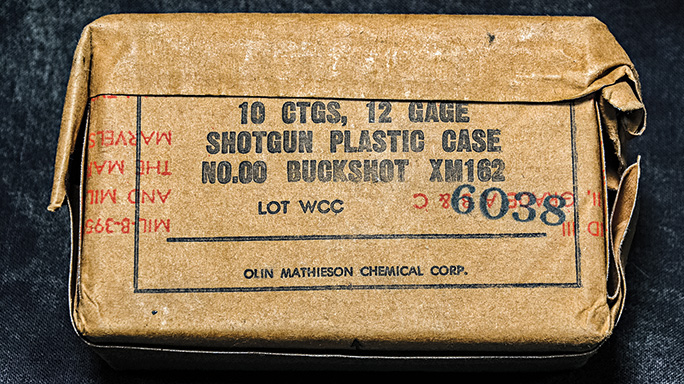

Early in the Vietnam conflict, M19 brass 00 buckshot loads left over from World War II were still in use, but as these ran out, two types were acquired: XM162 00 buckshot and XM257 #4 buckshot. The XM162 load was the most widely used. Both types were packed in cardboard boxes holding 10 rounds then wrapped in foil wrappers to inhibit moisture. Both the cardboard boxes and the wrappers were marked with the designation of the shells—“10 CTGS, 12 Gage SHOTGUN PLASTIC CASE NO. 00 BUCSHOT XM162”—and a lot number. XM257 boxes and wrappers were similarly marked but with the XM257 designation and #4 buckshot. Model 77Es would have likely been used at some point to fire the flechette rounds that were tested in Vietnam during 1967 and 1968. These aerodynamic projectiles offered longer range but less lethality than buckshot.

Rare Collectible

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Though the 77E undoubtedly saw combat, I cannot remember reading any narratives of its use. In his excellent Complete Guide To United States Military Shotguns, Bruce Canfield mentions that U.S. Marine 2nd Lt. John Bobo used a 77E in winning his Congressional Medal of Honor on March 30, 1967, in Quang Tri Province. Although the Stevens shotgun is not mentioned in Bobo’s CMH citation, it is worth quoting anyway:

“Citation: For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty. Company 1 was establishing night ambush sites when the command group was attacked by a reinforced North Vietnamese company supported by heavy automatic weapons and mortar fire. Second Lt. Bobo immediately organized a hasty defense and moved from position to position encouraging the outnumbered Marines despite the murderous enemy fire. Recovering a rocket launcher from among the friendly casualties, he organized a new launcher team and directed its fire into the enemy machine gun positions. When an exploding enemy mortar round severed 2nd Lt. Bobo’s right leg below the knee, he refused to be evacuated and insisted upon being placed in a firing position to cover the movement of the command group to a better location. With a web belt around his leg serving as a tourniquet and with his leg jammed into the dirt to curtain (sic) the bleeding, he remained in this position and delivered devastating fire into the ranks of the enemy attempting to overrun the Marines. Second Lt. Bobo was mortally wounded while firing his weapon into the main point of the enemy attack but his valiant spirit inspired his men to heroic efforts, and his tenacious stand enabled the command group to gain a protective position where it repulsed the enemy onslaught. Second Lt. Bobo’s superb leadership, dauntless courage, and bold initiative reflected great credit upon himself and upheld the highest traditions of the Marine Corps and the U.S. Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life for his country.”

It can be deduced that Bobo used the shotgun effectively in firing into the enemy attempting to overrun the position, as the shotgun would have been very effective at close range against a mass attack.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Despite the fact that the Stevens 77E was one of the more widely used shotguns of the Vietnam War, it is little known outside the ranks of U.S. shotgun collectors or weapons historians. It isn’t as “sexy” as the trench guns that still saw action, nor as well known as the Ithaca Model 37s used by the SEALs or the Winchester Model 12s used by the Marines. The Stevens Model 77E is also one of the toughest U.S. military shotguns to find.

- RELATED STORY: Stevens Unveils Four New 20-Gauge Shotgun Models

When the United Stated pulled out of Vietnam, most Model 77Es were left behind. Some did remain in the U.S. or return with troops redeploying, but unlike earlier martial shotguns they weren’t sold off as surplus.

Most of those that do turn up were supplied by the Department of Defense to police departments, which later sold or traded them. These weapons make great Vietnam collectibles or additions to U.S. shotgun collections, but count on paying up to 60 times what they originally cost the U.S. government if one happens to turn up.

For more information, visit SavageArms.com.