Immediate first aid in the field is critical to survive serious line-of-duty injuries.

Law enforcement today is, thankfully, paying more attention to that than ever. At the 2014 International Law Enforcement Educators and Trainers Association (ILEETA) conference, hundreds of us had the privilege of watching Eric Dickinson humbly accept the Trainer of the Year Award, sponsored by Law Officer magazine. His training has focused on self-treatment of trauma such as gun-shot wounds, and the treatment of downed partners as well as civilian victims immediately at the scene. We’ll never know how many lives this master instructor has saved. Look for his book The Street Officer’s Guide to Emergency Medical Tactics.

The Hippocratic Oath for medical professionals is often interpreted to begin with “First, do no harm.” For first responders, that could be translated as “First, prevent further life-threatening wounds from being inflicted.” Before pocket tourniquets and Israeli battle dressings can be applied, the opposing gunfire has to be extinguished. Here are some examples to drive this point home.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Fighting Back

Case One occurred in May of 2014 in Salt Lake City, Utah. Officers Mo Tafisi and Daniel Tueller stopped an SUV for having one headlight out. The driver ambushed them, opened fire with a stolen gun and seriously wounded both officers. But they returned fire instantly, dropping the would-be cop-killer and allowing the officers to immediately apply first aid as they waited the response of paramedics and ambulance.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Tueller, a year and a half on and the son of famed police survival instructor Dennis Tueller, and nine-year veteran Tafisi each credited the other with saving their lives.

“The driver ambushed them, opened fire with a stolen gun and seriously wounded both officers. But they returned fire instantly, dropping the would-be cop-killer …”

Case Two occurred in Chicago in June of 2014. During another “routine traffic stop,” the driver ambushed a pair of officers. A 31-year-old CPD officer with six years on took a bullet safely on his body armor, and his 12-year veteran partner, 38 years old, was hit in the knee. Before the gunman could finish what he tried to start, however, the police returned fire and neutralized him. The man survived and was charged with the attempted murder of police officers—and, more importantly, both officers survived, too.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Obviously, a trained and armed partner is a tremendous asset in these situations. Sometimes, the partner doesn’t wear a badge. In Case Three, which occurred almost 100 years ago in Sweetwater, Texas, hitmen attempted to assassinate famed Texas Ranger Frank Hamer, who was with his wife Gladys at the time. Early in the fight, Hamer was shot in the shoulder. Using his other hand, Hamer drew a Smith & Wesson Triple Lock and put a .44 Special bullet through the heart of the man who had shot him, killing the attacker instantly. Meanwhile, Hamer’s wife returned fire at the other assailants with her own gun, a Colt Pocket Model semi-automatic. The Hamers prevailed. Critical survival factors in this situation included being able to access and fire a weapon with either hand and having a spouse prepared for off-duty emergencies.

But what if there is no partner at all? Case Four, which took place in Hawaii some years ago, was another traffic stop turned deadly. As an officer approached his car, a man leaned out of his car window and opened fire with a 7.62x39mm rifle, wounding the cop multiple times. Sprawled out on his back, grievously wounded, the lawman returned fire from the supine position with his department-issued S&W Model 5906. When the gun ran empty, he reloaded while still on his back, aimed and finished the fight. When it was over, the corpse of the gunman hung from the driver’s window, riddled with 9mm bullets, and an ambulance picked up the officer. He survived to become a role model of indomitable determination.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

For Every Possibility

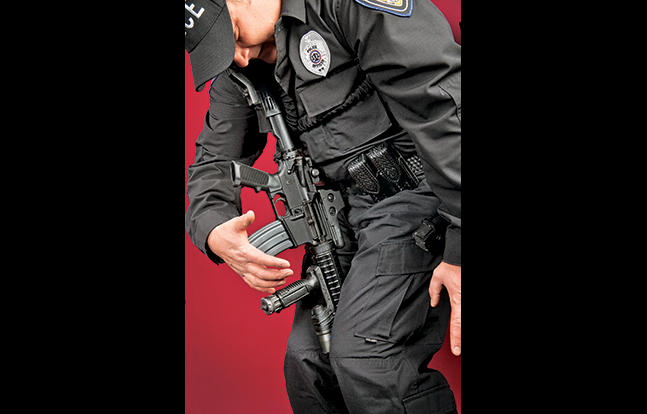

A great many wounds are inflicted to arm areas, particularly the gun arm; on either side of a gunfight, shots tend to cluster near the opponent’s weapon. This means the officer must have the discipline to aim at the opponent’s vital areas, but it also means that every cop must be prepared to draw, operate and reload their weapon single-handedly with either hand.

Officers need to be familiar with the most effective methods of returning fire from every conceivable position: down on either side at all angles, prone or supine, with one or both hands. Lower-body injuries may eliminate the option of tactical movement to cover. Dropped to your butt or down to both knees, a hail of well-directed bullets from your own weapon may be your only “shield” against incoming fire.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Today’s utilitarian police uniforms with cargo pockets make it easier than ever to keep trauma dressings and tourniquets immediately available on your person. Above all, training is key. For supplemental reading, I recommend the aforementioned Dickinson book as well as Tactical Anatomy by Dr. Jim Williams. Williams, a veteran ER doctor and police surgeon, also offers an excellent two-day course. You can contact him at tacticalanatomy.com.

As of this writing, Salt Lake City Police Officers Tueller and Tafisi are recuperating from their serious wounds. They have workman’s comp, of course, but both men have large families and their injuries have kept them from working overtime.

Donations for both hero cops’ families can be sent to Dennis Tueller, 1733 W. 12600 S. #113, Riverton, UT 84065, or email dennis.tueller@gmail.com.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below