Even before the turn of the last century, gun-makers were working in earnest to design a practical self-loading pistol.

The first real breakthrough was by an Austrian designer named Joseph Laumann, whose patent was assigned to the Österreichische Waffenfabrik Gesellschaft at Steyr in Austria. The 1892 Schönberger-Laumann pistol was one of the first autoloaders ever produced. In 1893, German arms designer Hugo Borchardt and his colleague Georg Luger developed the Borchardt Automatic Repeating Pistol, an unusual-looking gun that held within its design Georg Luger’s toggle-lock action, which would become the foundation for Luger’s remarkably successful 9mm introduced in 1900.

Another soon-to-be-famous German arms-maker, Peter Paul Mauser, had introduced an entirely different approach to the Borchardt and Luger designs in 1895 using a bolt mechanism inside the slide to extract and eject the spent cartridge casing, cock the hammer and strip a fresh cartridge from the magazine as the slide rebounded and closed. If that sounds vaguely familiar, it is the way almost every semi-auto pistol in the world works, only the Mauser’s barrel and slide were one piece. The Mauser C96, better known today as the “Broomhandle,” became one of the most successful handguns in history.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

But success must be measured by more than achieving a place in history; it must ultimately be gauged by its longevity throughout history, and there is only one handgun design from the very early 20th century that has remained in continual use to this very day—the Colt Model 1911.

Browning’s Designs

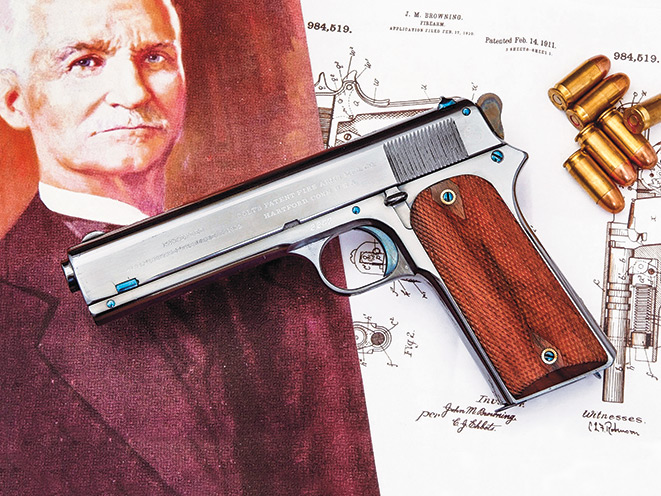

John Moses Browning’s earliest patent for a semi-auto is dated April 20, 1897, a date that would appear on the slides of Colt semi-automatic pistols for nearly half a century. Between 1900 and 1911, Browning’s designs would make Colt one of the world’s leading producers of self-loading pistols. The road leading to the development of the Model 1911 was well traveled by Browning with an entire series of semi-auto designs for Colt beginning in 1900.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

RELATED STORY: How To Build Your Own 1911 Pistol At Home

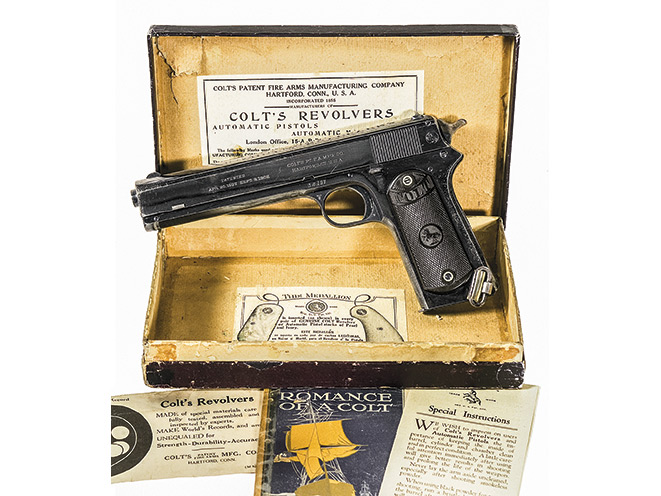

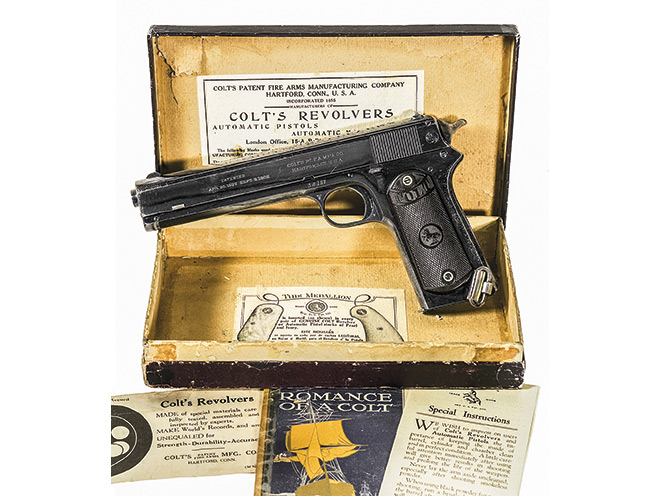

The Ogden, Utah, arms designer and his family were responsible for one of the earliest small-caliber autoloaders to find favor with lawmen at the turn of the century, the Belgian-manufactured FN Model 1900 chambered in 7.65mm (.32 ACP). At around the same time, Browning licensed his 1897 patent design to Colt for its own Model 1900, which was chambered in the new .38 rimless smokeless caliber (originally called a “Colt Automatic Pistol Hammerless,” or CAPH cartridge, and later shortened to ACP), a cartridge more closely related to the .38 Long Colt, then in use by the U.S. military for double-action Colt revolvers. Though only produced through 1903 and limited to around 3,500 guns, Browning’s Model 1900 formed the basis for an entire series of semi-automatic pistols that would lead to the Model 1911.

From 1900 to 1911

One of the great incentives for further development by Browning and Colt in the early 1900s was the U.S. military’s keen interest in seven-shot semi-autos. Both the Army and Navy procured Colt Model 1900 pistols for evaluation, around 50 for the Navy and 200 for the Army. The improved Colt Model 1902 (sporting) automatic pistol found even more favor with the government. Changes in the design included a rounded hammer, a shorter firing pin (deemed necessary to avoid accidental discharges if the hammer were inadvertently struck while a cartridge was chambered), a dovetail-mounted rear sight and checkered, hard rubber grips. To meet Ordnance Department requirements, the military versions had a longer grip squared at the butt (as opposed to the rounded-contour grip on civilian models), a lanyard swivel on the lower left side of the grip frame, a slide stop on the left side of the frame and an eight-shot magazine, whereas civilian versions carried one less round. The military’s Model 1902 remained in the Colt catalog until 1928, with production reaching over 47,000 examples.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

In between production of the Model 1902, the Model 1903 and development of the first Hammerless semi-automatic Colt pistols came a design that is regarded as the quintessential stepping stone to the 1911, the Model 1905. This new .45 ACP handgun was cataloged as the “Model 1905 .45 Automatic Pistol.” The similarities between the Model 1905 and the later Model 1911 are unmistakable, as are the differences. Colt’s first .45-caliber semi-auto used a rimless smokeless cartridge designed by Browning. The new gun and cartridge were exactly what the U.S. military had been waiting for.

Unfortunately, the Model 1905 left a lot to be desired as a military sidearm. To the average serviceman, it was complicated compared to a revolver, and the .45 ACP recoil was substantial. Nevertheless, in 1907 the U.S. government placed an order for 200 of the new semi-auto Colts for evaluation. The military versions required Colt to develop a grip safety, which was engineered by Colt factory designers Carl Ehbets and George Tansley, who patented the design. Browning had also patented a similar grip safety device first seen on the FN Model 1905 and three years later on Colt’s Model 1908 Pocket Hammerless models.

RELATED STORY: 13 Iconic Combat Handguns Throughout History

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

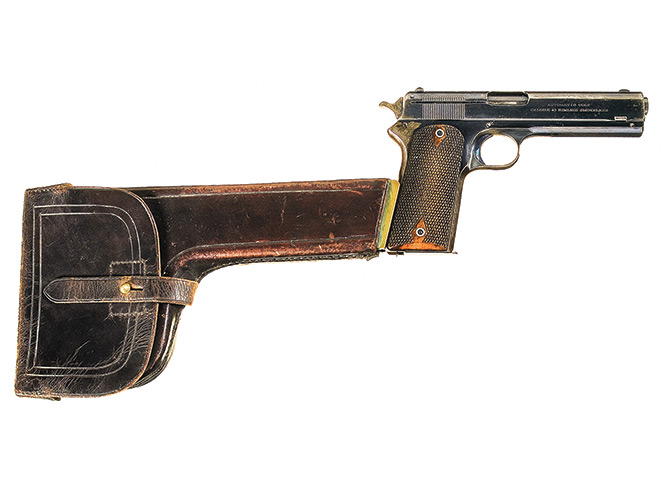

The .45-caliber 1907 contract models (which differed from civilian models built in 1907) also had to be designed to accept a detachable shoulder stock (which Colt later offered as a shoulder stock/holster for the civilian market), be configured to use a spur-type hammer rather than the civilian-style rounded hammer (there were four different hammer designs throughout the gun’s production history), and have a lanyard loop so soldiers could tether the handgun to a braided lanyard worn over the shoulder. In addition, the government wanted modifications to the ejector and ejection port, which was enlarged. All 200 guns, which had their own serial number range, were equipped with a grip safety and are regarded as the rarest variation today. Cavalry field tests still found numerous faults with the design for military applications, however.

Although the government’s tests in 1907 were somewhat damning, Colt and Browning reworked the design in 1909 and again in 1910 to meet the military’s requirements. Among the most notable improvements was a change from the double-link barrel locking system of the 1905 to a single toggle link that would be used in the Model 1911. The 1905 had the barrel pinned to the frame via two pivoting barrel lugs, thus it was attached at both the muzzle and breech ends, which made it an inherently accurate handgun but also much harder to field-strip. The slide was secured to the frame by a wedge passing through it just below the muzzle, and over time this would prove to be a design weakness and one of two principal points of failure with the Model 1905 in military field tests.

Upon firing, the 1905 barrel would pivot backward, disengaging from corresponding grooves in the slide, allowing it to unlock from the barrel and continue its rearward movement. In order to take the 1905 barrel out of the frame for field-stripping, two small pins had to be punched out—a much more complicated method and the second point of failure with pins occasionally fracturing. To alleviate the design weakness, Browning devised his single toggle link, which also served to anchor the barrel, thus making disassembly much easier and an overall much stronger design. This also established the tilting barrel, which has remained a global standard among arms-makers for over a century.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

For the 1910 military trials, Browning and Colt made additional changes to the 1905’s grip design and angle, which Browning stated would further improve handling. After an initial field test in February of that year, Colt made a few more modifications, at which point the 1910 looked essentially like the 1911, with the exception of a thumb-activated safety. A second series of tests was conducted in November, and the military’s Board of Officers rendered a more favorable opinion but presented yet another list of critiques that Colt would have to address. These would lead Browning and Colt to the final design for the Model 1911.

Final Military Trials

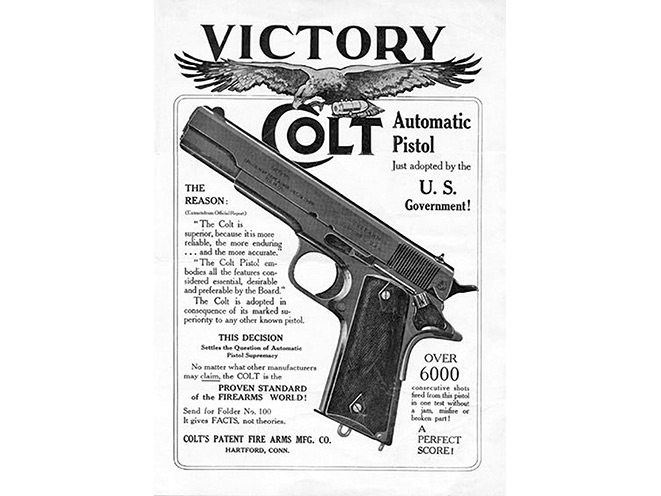

On March 3, 1911, the new Colt semi-auto design performed flawlessly, firing 6,000 rounds of ammunition, and addressing all of the Ordnance Department’s concerns, including the addition of an external safety so the gun could be carried with the hammer cocked (although military protocols stated that the guns were to be carried with an empty chamber). On March 29, 1911, U.S. Secretary of War Jacob M. Dickinson approved the selection of the Colt Browning as the “Automatic Pistol, Caliber .45, M1911.” The government’s initial order was for 31,344 pistols. Six years later, the 1911 would see service in World War I. By the end of World War II, more than 2,550,000 Model 1911/1911A1s had been produced for the U.S. government.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

RELATED STORY: 20 Aftermarket Grip Panels For Your 1911 Pistol

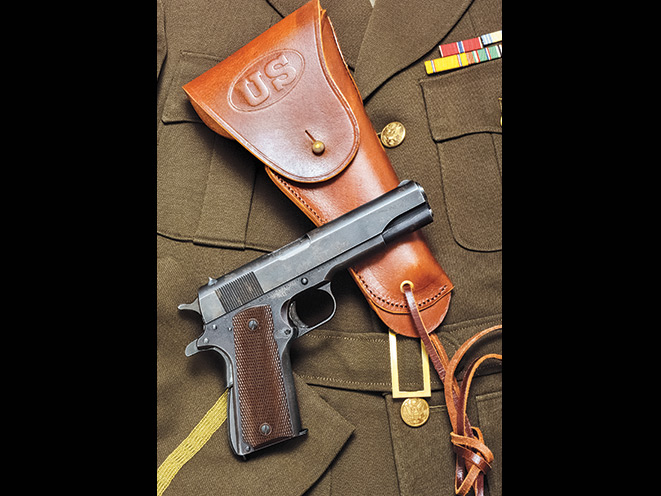

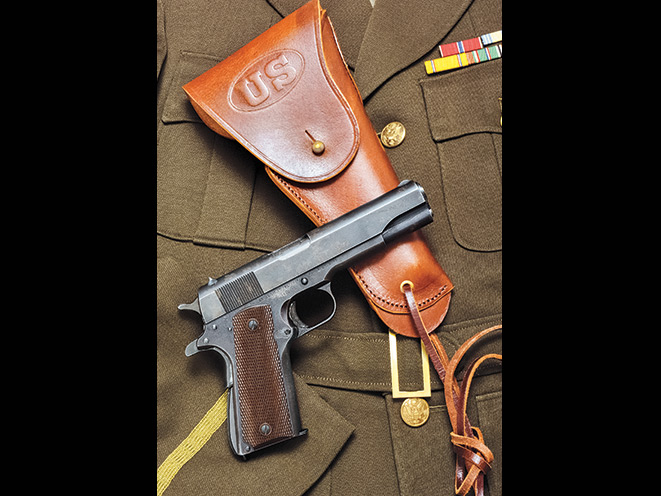

The Model 1911 was adopted as the official sidearm of the U.S. Army, Navy, Marine Corps and federal agencies, and remained in continual use until the improved Model 1911A1 was introduced in 1924. The 1911A1 was distinguished by a shorter trigger, a larger grip safety and, most notably, an arched, knurled mainspring housing that fit the palm swell of the shooter’s hand. The new model eventually replaced all of the original military 1911s and became the standard commercial version, although today’s modern 1911s often have the original flat mainspring housing, which has become the more desirable of the two designs.

Wartime Makers

Two World Wars increased demand for the Model 1911 beyond Colt’s production capacity, requiring the company to license other manufacturers to produce guns to meet military quotas. The first request came in 1914 (three years before the U.S. entered WWI) with approximately 30,000 guns being produced at the Springfield Armory through 1915. From 1918 to 1919, Remington-UMC manufactured over 21,500 Model 1911s. North American Arms in Quebec, Canada, produced an additional 100 in 1918.

WWII demands again outstripped Colt’s capacity, and guns were made from 1943 to 1945 by Ithaca Gun Co. and Remington Rand, totaling over 1.3 million 1911A1s. In 1942, Singer (the sewing machine company) began manufacturing the 1911A1 (only about 500), and in 1943, Union Switch & Signal Co. produced as many as 400,000 1911A1 models for the war effort. These guns all bear their maker’s names and markings. Wartime Colts also bear special stampings, including “United States Property” and the specific branches of service.

The Model 1911 was intended to be a military sidearm but its popularity in the civilian marketplace was just as robust, leading Colt to develop the Model 1911A1 National Match pistol in 1933. This was a Colt Government Model designed for target shooting. The National Match was equipped with a “Super-smooth, hand-honed target action—selected ‘Match’ barrel—and two-way adjustable rear sight.” The original National Match pistols were manufactured up to the beginning of WWII, when military demand superseded the needs of the civilian market.

The Model 1911A1 also became available in .38 Super beginning in 1928. Colt then introduced the .22-caliber Ace in 1931 and the .38 Super Match (a .38 Super variant of the .45 ACP National Match) in 1934. Throughout Colt’s production, there were also special custom shop models, contract versions for foreign governments, factory-engraved guns, .22-caliber conversion kits, the introduction of the compact Commander in 1949 (fitted with a shorter slide and a 4.25-inch barrel), and the postwar reprise of the 1911 target model as the Gold Cup National Match, introduced in 1957. The Model 1911A1 was pretty much the gun in America by the late 1950s. In the second half of the 20th century, more police departments would make the switch from wheelguns to Colt 1911s.

RELATED STORY: 8 Compact 9mm 1911 Pistols

Today, Colt’s latest versions of the 1911 are used by elite U.S. military and special operations units as well as various local, state and federal agencies across the country and around the world. After more than a century, the Colt Model 1911 is still one of the most significant firearms designs of all time, and there is no sign that this handgun will ever go out of style. That is the ultimate definition of success.

Editor’s Note: Portions of this article are excerpted from the author’s book, Colt: 175 Years, published by Barnes & Noble.