The battles at Lexington and Concord in April of 1775 launched the American Revolution, but the “shot heard round the world” would’ve meant nothing if not for a lead ball fired two years later near Saratoga, N.Y.

Rally Shot

On Oct. 7, 1777, British Brigadier General Simon Fraser boldly rode onto Bemis Heights, rallying his troops in a desperate fight with rebel sharpshooters. American Major General Benedict Arnold marveled at Fraser’s audacity but feared it, too. “That man on the gray horse is a host unto himself and must be disposed of,” Arnold told Colonel Daniel Morgan, the sharpshooters’ commander.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Morgan sent a trusted marksman up a tree to target Fraser, who soon fell from the saddle, shot in the guts. The rally sputtered, the redcoats fled and the rebels won the Saratoga Campaign—and much more.

It was the first major victory of Americans over a similarly sized British force and proved the might of General George Washington’s “amateur” army. But Saratoga also inspired France, a longtime foe of England, to ally with the colonists. It set the stage for America’s Revolutionary War victory—which motivated liberty seekers across the globe—thanks to one rifleman. Tradition says he was an Irish backwoodsman from Pennsylvania, one Sergeant Timothy Murphy.

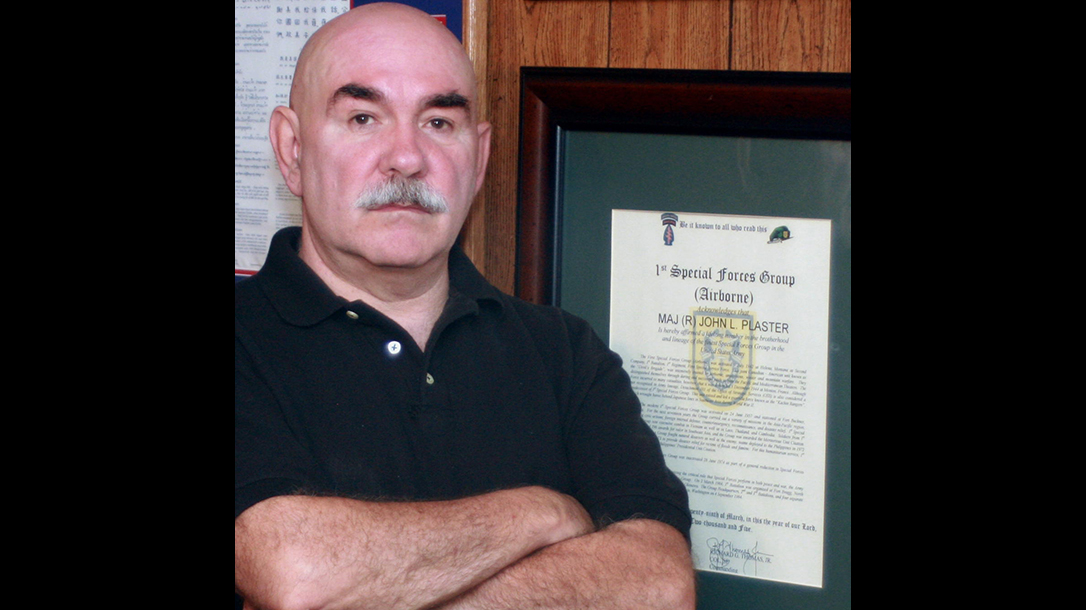

“Some historians hint that this is the most decisive shot in all military history,” said John L. Plaster, author, teacher of modern sniper techniques and former U.S. Special Forces operator in Vietnam. “I am a great fan of Timothy Murphy.”

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Elite Infantrymen

Little is known about Murphy, but records show he was born in 1751 to Irish immigrants, according to the New York State Military Museum. His family settled on the frontier near present-day Sunbury, Penn.

The rifle, Plaster said, “was an everyday tool” for food and security, and Murphy “couldn’t waste lead or powder”—perfect training for Morgan’s light infantrymen. Although considered elite, these troops, including Morgan, a Virginia pioneer, had no official uniforms. They mostly wore linen hunting clothes, sometimes festooned with fringes or Native American designs.

Riflemen served with little pay and likely felt stress about home, with crops in the field and families vulnerable to raids by indigenous warriors, Plaster said. They marched across the northern colonies, even in harsh weather. Most wore moccasins, which were prone to wear out, so they carried several pairs. But what distinguished them most was their expert handling of the frontier longrifle.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The Progressing War

Plaster, who retired as a major, served with the Studies and Observations Group (SOG), conducting secret reconnaissance missions during the Vietnam War. He writes a lot about SOG, and also military snipers and their particular techniques. Hence his appreciation for Timothy Murphy.

He said infantry tactics during the American Revolution involved mass volleys from smoothbore muskets with effective ranges of about 50 yards.

“Ninety-five percent of the infantry were not riflemen,” he said. But, he noted, rebel long rifles could hit targets at 200 yards and farther thanks to the grooved rifling in their gun barrels, perfected by German and Swiss gunsmiths.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

After Lexington and Concord, the rebels surrounded British-held Boston. Murphy, at age 24, joined the siege with the Northumberland County Riflemen and harassed the redcoats with well-aimed lead.

The British evacuated Boston by sea, regrouped in Canada and, in 1776, sailed south to invade New York City from Long Island. Murphy redeployed there in August. But the British overwhelmed the Americans in Brooklyn.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Washington’s army, facing annihilation, escaped in a massive night retreat across the East River, under a convenient—and some say miraculous—cover of fog. According to the museum, Murphy also fought at Trenton and Princeton.

Building a Team

In January 1777, the British released Colonel Morgan in a prisoner exchange, having captured him at the Battle of Quebec. Washington tasked him with forming a new unit—one that could seize the battlefield advantage with long rifles.

Recruiting began for Morgan’s Provisional Rifle Corps. Murphy volunteered and easily qualified by hitting a 7-inch target at 250 yards, the museum reported. The corps’ guerrilla tactics enhanced marksmanship. Instead of forming ranks and unleashing short-range lead, the rebels amassed kills at farther distances with precise shots from concealed positions.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

But they had to shoot and move fast, Plaster said. Redcoats, he explained, knew where to send bayonet charges by tracking the smoky plumes that billowed from each long rifle shot.

“In the heat of battle, what mattered most was the speed of reloading,” Plaster said. “But imagine the British closing the distance, elbow to elbow. If you don’t move, you’re going to get a bayonet in the belly.”

In August, Morgan’s 500 riflemen marched north to block a British land invasion of New York from Canada, commanded by Major General John Burgoyne.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Timothy Murphy Takes the Shot

Saratoga was a month-long campaign involving two major battles at Freeman’s Farm and Bemis Heights, where Fraser galloped onto scene, impressing Morgan as much as Arnold. After receiving his general’s order, Morgan, according to tradition, turned to Murphy and said, “That gallant officer is General Fraser. I admire him, but it is necessary that he should die. Do your duty.”

It took a couple of tries from the tree before the marksman mortally wounded Fraser, possibly with a double-barreled long rifle. But this shot required particular skill, Plaster said.

“I was at the Saratoga battlefield with a curator, and we estimated the range at 330 yards,” he said. “Nowadays, any competent rifleman could have hit General Fraser, but firing a rifle accurately back then was far more complicated.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

“There was more to it than just holding high and pulling the trigger,” Plaster added. “Think of it this way: Murphy pulls a trigger, but for a short time, he has to physically and mentally follow-through. The rifle may have gone click, but it still has to go through a whoosh and a bang.”

That might take a second or more, and the rifleman had to stay on target the entire time or his shot would be off.

Today, modern guns and ammo let a shooter launch a bullet in the fraction of a second. New riflescopes, rangefinders and bullet technology also boost accuracy.

“But back then, there was no such thing as match ammo,” Plaster said. “So what about a guy shooting with open sights with what was basically a shotgun slug? You’re starting with a very low ballistic coefficient. You’re shooting a bowling ball instead of a javelin. It would only be worse if it was square.”

Inspiring The French

Word of mouth carried Murphy’s story, but some historians say written accounts of Saratoga make no mention of him until almost 70 years after the battle. So, they suggest, any of Morgan’s men could’ve killed Fraser. Maybe, but no other names contest the legend, so it endures.

Although technology supplants Murphy’s skills, Plaster said today’s snipers can still learn from this rifleman; that one well-placed round can make history.

“His one shot brought France into the war,” Plaster said. “For the first time, a British field army was compelled to surrender to these American upstarts. That brought thousands of French troops with lots of artillery and sea power. For the first time, it was apparent that Americans could really win this war.”

Editor’s Note: Tactical Life originally published this story on November 1, 2018.