Learning to shoot straight is the easy part. Mastering the terminology and understanding what it means to your safety can be more challenging. The handgun trigger might be one of the best examples.

Do your eyes glaze over when the salesman asks, “Are you looking for double-action (DA), single-action (SA), double-action-only (DAO), striker-fired or double/single?”

Take heart, because most new shooters experience initial “action overload.”

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

And, truth be told, there are plenty of experienced shooters who still don’t fully grasp the concepts.

- RELATED: Combat Handgun’s 25 ‘Can’t Miss’ List For 2014

- RELATED: 12 New Compact & Subcompact Handguns For 2014

As an NRA-certified pistol, rifle and shotgun instructor—not to mention a range officer and gun salesperson—I routinely encounter novice shooters who are baffled by the strange new world of strikers, hammers, firing pins, sears and trigger poundage. It is a bit intimidating at first, but it isn’t rocket science.

Let’s start with the basics. Once ammunition is chambered, two things must occur in order for your gun to fire. First, you must pull the trigger. Doing so initiates the second step, in which the hammer or striker move forward and hit the primer cup or the rim of the ammunition cartridge. Every firearm involves essentially these two steps, but, through innovation, the number of ways by which the process can occur has multiplied.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Striker-Fired

The most popular action is the striker-fired model. A striker-fired weapon lacks a hammer or firing pin. Instead, it has a striker (basically a firing pin under spring tension). Various internal safeties prevent the striker from moving forward and igniting the primer until the trigger is fully depressed. These guns are very safe, despite the typical absence of a manual safety.

“… what I love about…striker-fired pistols is the consistent manageable trigger pull.”

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Some people cringe at the idea of no manual safety. When that happens, I point out that most striker-fired guns have a trigger safety and/or a grip safety, as well as an internal firing pin safety or drop safety. My colleagues tell people, “You can chamber a round, throw the gun down and play hockey with it, and it will not discharge until you pull the trigger.”

While I’ve used that line myself to underscore my faith in striker technology, I wouldn’t advise doing so, even with a Glock. But what I love about Glocks, Springfields and other striker-fired pistols is the consistent, manageable trigger pull, not to mention those multiple internal and external safety features.

Revolvers: SA Or DA

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The terms “double-action” and “single-action” simply refer to the job performed by the handgun trigger. An SA trigger performs a single task: It releases the hammer (which, in a traditional revolver, is cocked by your thumb). A DA trigger performs two tasks: It cocks and releases the hammer. Typically, a DA trigger is harder to pull because it has more work to do.

If you are buying a revolver for personal defense, an SA model, such as the Ruger Single-Six (typically in .22 LR) or an Uberti Cattleman (.45 Colt, .357 Mag or .44 Mag), is not the best choice. While today’s Western-retro SA revolvers are great for pleasure shooting and cowboy reenacting, the necessity of manually re-cocking the hammer may make them a tad impractical for self-defense.

Enter the DA revolver. There is no need to manually cock a DA revolver because the trigger performs that task internally. But shooters with small or weak hands can struggle with the heavier trigger pull. Because of this, it is wise to test the pull before you buy. If you select a revolver with an exposed hammer claw, you can always manually cock the hammer for a lighter pull, but then you are right back to the impracticality of older-style SA handguns.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

For concealed carry, many manufacturers have created “hammerless” models with no exposed claw to snag on clothing as you draw. With these models, there is no SA option. Love it or leave it. My favorite DA revolvers are the Ruger LCR and the Smith & Wesson 642 Airweight, both lightweight guns with reasonable trigger pulls. But I am a modern gal and not a huge fan of revolvers, no matter how evolved they are. My defensive guns are semi-automatics, ranging from traditional SA 1911s to the newer, innovative striker-fired styles.

SA Semi-Autos

John Browning’s still-wildly-popular 1911 has a comfortable SA trigger pull, but the backward/forward motion of the slide automatically re-cocks the hammer after you shoot. Thus, once you chamber your first round, you simply pull the trigger until the magazine is empty. All 1911-style guns, such as those made by Colt, Kimber, Sig Sauer and Springfield, are designed to be carried “cocked and locked.” That is, you chamber a round and turn on the safety. If you have to shoot, you must remember to disengage the safety, or it will be a short gunfight.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Many people—especially new shooters—like the idea of a manual safety because it appears to offer better protection against unintentional discharges. Likewise, in a high-stress situation, you need relatively little strength to depress an SA trigger.

Double-Action-Only

A double-action-only (DAO) semi-automatic—not to be confused with double-action/single-action (DA/SA)—is similar to its DA revolver cousin. The trigger both cocks and releases the hammer or striker, but there is no SA option if you don’t like the heavy pull.

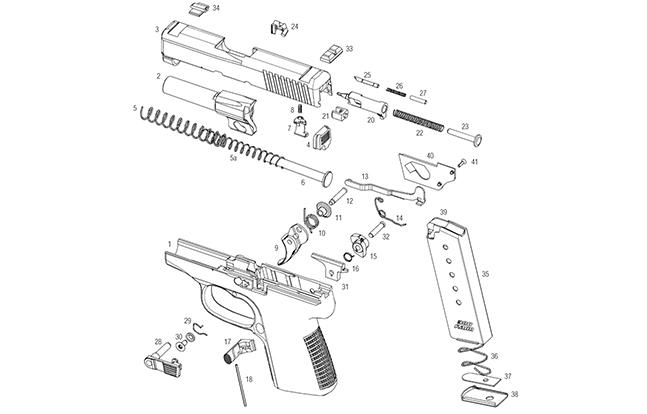

DAO handguns like the Kel-Tec P-11 and the Kahr PM9 offer two different price points in two dependable handguns. I love the smooth-shooting PM9 (which costs about $786). However, I am also a fan of the P-11 (retailing south of $300). The long trigger pulls aren’t hateful on either gun, and both offer manageable recoils. Fans of DAO guns say they value the consistent trigger pull, not unlike the SA models, albeit heavier. Internet chat rooms are rife with shooters who prefer DAO to DA/SA because they believe accuracy is harmed when you switch from heavy to light trigger pulls.

Double-Action/Single-Action

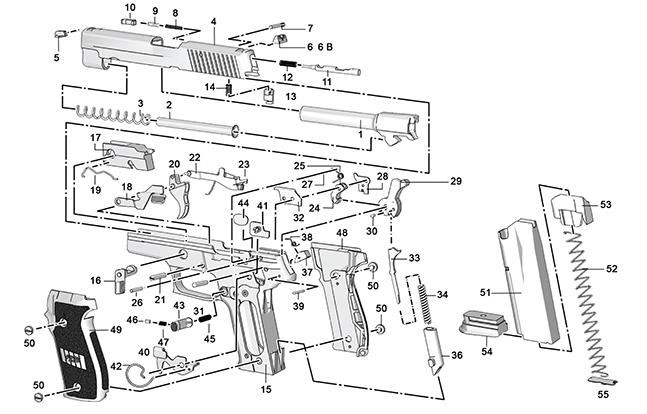

A DA/SA firearm offers a stout initial DA trigger pull before switching into lighter SA mode. Many shooters argue that the DA first pull of these guns is much heavier than the consistent pull of DAO models. The trigger reset can also take longer in the SA mode.

So, why own a DA/SA model? For starters, you can carry the gun without fear of unintentionally depressing the trigger. You’d have to work pretty hard to inadvertently fire a Sig P226 or a Beretta 92. There is an argument, too, that DA/SA triggers are the best training for every other gun on the market. “If you can shoot a double-single well, you can shoot anything,” I’m told.

All Capable

Confused yet? The best way to clarify things is simply to shoot several guns of each style. I own a Springfield XD 9mm, an XD-S .45, a Glock 19 and a Glock 35. I would trust any of them with my life, which is why I own them. Also, I figure that several million police officers can’t be wrong. Striker-fired guns shoot consistently and under the most adverse conditions. While I love my 1911 and my similarly-styled Sig P238, I am more likely to carry my Springfield or my Glock if I am “walking in dark places.”

So now that you’ve gotten “a little action,” you can decide what to do with this knowledge. Whether you opt for an SA, DA, DAO, DA/SA or striker-fired handgun, take time before you buy to shoot the gun you will trust your life to. With all these options, you should be able to find one that suits your needs perfectly. You should also be able to find one that you are comfortable operating. You will unknowingly make many life-and-death decisions during your stay on earth. This is one you can actually have some control over. Choose wisely.

This story was featured in the 2015 HANDGUN BUYER’S GUIDE. To subscribe to the HANDGUN BUYER’S GUIDE, please visit PersonalDefenseWorld.com/subscribe.