The Kingdom of Serbia regained its independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1878, after 419 years of Turkish domination. Continuing the unfortunate patterns of violence so prevalent in the area, Serbia found itself at odds with most of its neighbors for the 75 years that followed.

During World War I, Serbia was occupied by the Central Powers, but many thousands of Serb soldiers were evacuated by the Allies, reequipped and later fought with distinction on the Thesalonikii front in northern Greece until 1918. After the war, Serbia formed the core of the new “Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes,” which was renamed “Yugoslavia” in 1929. The kingdom’s multi-religious population of Serbs, Albanians, Macedonians, Croats, Slovenes, Bosnians and Montenegrins coexisted in a tense atmosphere acerbated by centuries of ethnic and religious distrust and warfare.

Serbia’s War Arsenal

In 1927, the Yugoslav arsenal at Kraguyevac began production of a copy of the FN Fusil Modèle 24, a 98-type Mauser short-rifle chambered for the 7.9x57mm. Known as the Pešadisjka Puška M.1924 (Infantry Rifle Model of 1924), it was the standard-issue rifle at the beginning of WWII. In 1941, the German Wehrmacht invaded Yugoslavia and rather handily defeated the Royal Yugoslav Army. Serbian nationalists, the Chetniks, led by Colonel Draža Mihailović and Communist Partisans led by Josip Broz Tito began a guerilla campaign against the occupying forces, which tied down many divisions of Axis troops who were badly needed elsewhere. The two guerilla forces apparently spent as much time fighting each other as they did the enemy, which led to some Chetniks cooperating with the Germans and the subsequent Allied recognition and support of Tito and his Partisans. In the post-war years, the Communist Party under Tito’s leadership became the new ruler of Yugoslavia.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

In the post-war period, the Kraguyevac arsenal received a proper, socialist designation—Zavodi Crvena Zastava (Serbian for “Red Flag Institute”)—and began production of the Puška M.48, a Mauser that remained in frontline service well into the early 1960s. Tito proved adept at Cold War intrigues, and while Yugoslavia was officially a “neutral” country, her foreign policy tended to be more pro-Soviet than not. When it came time to upgrade its weaponry, the Yugoslav People’s Army decided to standardize on Warsaw Pact equipment and adopted the Samozaryadnya karabin Simonova obrazets 1945g, better known as the SKS carbine. Designed by Sergei Gavrilovich Simonov, the SKS, a gas-operated, semi-automatic weapon, was the first weapon chambered for the Soviet-designed intermediate cartridge, the 7.62mm patron obr. 1943g.

SKS In Motion

As the bullet travels down the SKS’s barrel, powder gases are vented into a tube above the barrel where they force a piston rod to the rear, which moves a bolt carrier. After about 8mm of movement, the carrier lifts the rear of the bolt up, unlocks it from the receiver and carries it to the rear. The spent cartridge case is then extracted and ejected, the hammer is cocked, and the recoil spring is compressed at the rear of the receiver. The spring then pushes the bolt forward, where it picks up the next round from the magazine and chambers it. As the bolt goes into battery, the carrier pushes it down, locking it into the receiver again. The SKS utilizes a 10-round magazine that is loaded in place with chargers and hinged at its front so it can be opened to safely unload the rifle or for cleaning. One of the SKS’s most characteristic features is a permanently attached bayonet, which can be folded back into a cutout in the forearm.

Small numbers of SKSs saw combat with the Red Army late in WWII. While the SKS was adopted as standard issue in 1949, it was soon replaced by the AK47. The SKS was widely used by Warsaw Pact armies, and variants have been manufactured in Poland, Hungary, East Germany, Albania, Romania, China, North Korea and North Vietnam. As Eastern Bloc armies upgraded to AK-pattern weapons, vast numbers of SKSs were supplied to the USSR’s “allies” and proxies in Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Latin America—all in the name of socialist brotherhood, of course.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

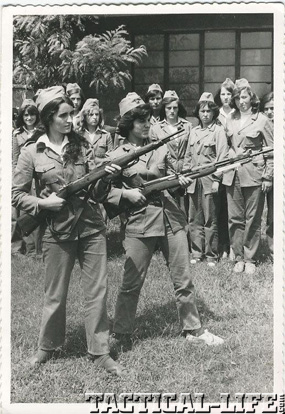

As produced at Zavodi Crvena Zastava, the Yugoslav version of the SKS—the Polu-automatska puška M59 (semi-automatic rifle model 59)—was a more-or-less exact copy of the Soviet SKS, except it did not have a chrome-lined barrel. The Yugoslav Peoples Army began receiving the new rifle in 1964 and, as soldiers around the world so often do with their weapons, bestowed it with the feminine nickname “Papovka” (“Pap” for Polu-automatska puška). Since the late 1940s, Yugoslavia had been an active participant in the international arms trade and, considering Tito’s political proclivities, it wasn’t long before Yugo M59s were in service with various third-world armies and national liberation groups such as the Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola (MPLA), to whom the Yugoslav government supplied large amounts of military aid.

While the Avtomat M.64 (an AK47 variant) had been approved, Yugo M59-type weapons remained in frontline service with the Yugoslav People’s Army for almost another decade. Yugoslav military tactics placed great emphasis on the use of rifle grenades. But being the M.64 was not capable of firing them, in 1967 the Polu-automatska puška M59/66 was adopted, which featured a permanently attached grenade launcher on the barrel and a fold-up grenade launching sight. In WWII, the U.S. Army did not develop a grenade launcher for the M1 Garand until late 1943 and so continued to issue M1903 Springfield rifles to each unit for grenade-launching purpose. Similarly, the Yugoslavs may have intended for each M.64-armed unit to have several grenadiers equipped with Yugo M59 and M66 rifles. But as production and issue of the Avtomat was delayed a number of times, the Yugo M59 and M66 came to be a general-issue infantry rifle.

Grenade-Launching

When the M59/66’s grenade-launching sight is raised, the gas system is automatically blocked and the action must be manually cycled—rifle grenades are fired with special blank cartridges, and this feature helps ensure that a live round is not loaded from the magazine. When the sight is folded down, it is locked in place by a serrated catch on the end of the gas tube, and moving this catch unblocks the gas system, once again allowing semi-automatic operation. The fold-up grenade-launching sight ladder has two different sets of range markings: those on the left are for anti-materiel (tanks, vehicles, buildings) grenades and those on the right for anti-personnel grenades. The differences in weight and flight ballistics and launching blank charges means each type of grenade needs a specific range marking on the sight ladder. To aim the rifle grenade, the appropriate range V-notch on the sight ladder is lined up with the nose of the grenade and pointed at the target.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

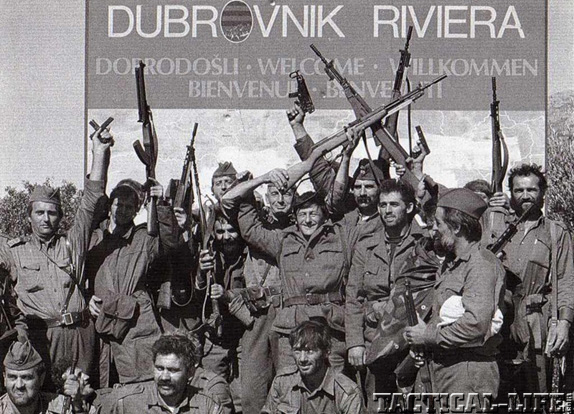

A final version, the M59/66A1, was adopted in 1970 and fitted with fold-up, luminous night sights and had a chrome-plated bore. Production only lasted about 18 months before the army adopted an improved assault rifle—the Avtomat M.70—which was capable of launching rifle grenades. As more M.70s came into service, the Yugoslavs sold many of their surplus Yugo M59 and M59/66 rifles to customers around the world. The Yugoslav version of the 7.62x39mm—the 7.62mm Metak Yugo M59—consisted of a rimless, bottlenecked case loaded with a boat-tail, 123-grain, jacketed, steel-core bullet moving at approximately 2,400 fps. In 1967, the 7.62mm Metak M67 was adopted. Its flat-base, lead-core bullet was shorter and shifted the center of gravity rearward, allowing the bullet to destabilize and create a more effective wound channel. Yugo M59 and M67 cartridges are found with brass and steel cases.

With the death of Marshall Tito in 1980, the ethnic tensions and conflicts that had always simmered just below the surface of Yugoslav society erupted into violence. Croats, Slovenes, Bosnians, Macedonians and others, who had been dominated by the Serbians since the 19th century, demanded increased autonomy and even outright independence. One could not turn on the television news without being regaled with tragic stories and film from Serbia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Slovenia, Belgrade, Sarajevo and Kosovo. It was common to see Serbian police and reservists or the nationalist irregulars fighting them, armed with Yugo M59 and M59/66 rifles.

Heading Downrange

Samco Global Arms provided me samples of the Yugo M59 and M59/66 rifles to evaluate. Both were in unissued condition, with nice blue finishes, matching serial numbers on all major parts and unmarred beech stocks. Test-firing of the M59/66 was conducted from a Caldwell Lead Sled, which not only alleviated the symptoms of recoil but also removed most human error and provided consistent positioning of the rifle. Winchester provided me with a supply of their U.S.-brand 7.62x39mm cartridges loaded with 123-grain FMJ bullets, which more or less duplicate the ballistics of the Yugoslav-issue cartridge.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Considering the rifle’s rather coarse sights (and my 60-something-year-old eyes), I erred on the side of caution and placed my targets on the 75-yard backstop. The trigger had a short take and rather crisp let-off, and only a few rounds were expended to determine where it was printing before I began to shoot for score. I fired four five-shot groups, all of which came in around 3 inches in size, printing a bit left of point of aim. I then placed two combat silhouette targets on the 100-yard backstop and rapid-fired a full magazine at each target, using just a sandbag rest. I was pleased to see that all 20 rounds impacted in the X- and 9-rings of the targets, which I consider more-than-adequate “combat accuracy” from such a rifle.

I found the M59/66 a very admirable little rifle. In fact, the only complaint I can voice is the open-notch rear sight, which made it difficult to take a fine or fast sight picture. I have always found it difficult to understand why Soviet designers never used the aperture rear sight on their military rifles.

Special thanks to good friend and fellow author Branko Bogdanovic for the information and photos he supplied.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Check out this article about the Top 20 AK Rifles & Soviet Weapons!