Often forgotten, the .41 Magnum is still around and offers a great alternative to the .44 Magnum. First unveiled to the world by famed author Elmer Keith in 1964, and with the help of Smith & Wesson, Remington and Bill Jordan (who envisioned it as the perfect tool for law enforcement), over time it has established a spot in the long list of usable handgun calibers.

The Classic 41 Magnum

However, it’s traveled a rocky road since its introduction. Just a notch above the popular .357 Magnum and a notch below the .44 Magnum, looking back, this .41-caliber round hasn’t always had it easy. While it enjoys a lower recoil sensation than some of the calibers around it, the .41 Magnum still has a good trajectory for hunting. It can, when handloaded, move the power scale up and down to suit any occasion. Available years back in a wide assortment of both handguns and rifles (the Marlin 1994 was an example), the pickings are slim now, but if you look closely—to Ruger, for example—you can still find the cartridge in the famed New Model Blackhawk series in various barrel lengths. My guns included the traditional Smith & Wesson Model 57 and the up-to-date Model 657 Classic Hunter complete with a 6-inch barrel and full-length barrel shroud.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

After some research, loading, testing and shooting, the .41 Magnum turned out to be very pleasurable. I completed the testing at the traditional 25 yards. Although I entertained clamping the gun in a Ransom rest, I rested the front of the gun on a sandbag. I let the free recoil roll by hand upward after every shot. The .41 Magnum never brought on a case of flinching. As I recall, the morning passed smoothly and enjoyably with the big-bore handgun.

Loading The .41

At that time, the gun and the .41 Magnum were new to me, so gathering materials for handloading took some time. I purchased new Remington brass, which is still available, though in short supply; a set of RCBS carbide dies; bullets from Sierra, Hornady, Remington and Speer; and CCI 300 and 350 primers. Then I was all set to go.

Being a traditionalist, I grabbed a pound each of Unique for mid-range loads as well as H110 and 2400. History shows that Unique has been on the market since the turn of the century. It still remains a popular powder for a wide range of magnum cartridges. Born in 1962, Hodgdon’s H110 is a double-based powder and is fine-grained for ease of metering through any measure. Finally, Alliant 2400 goes back to 1933 and is perfect for the .41 Magnum. But Olin’s 296, IMR-4227 and Herco can also be used in this cartridge with good success.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

On the Bench

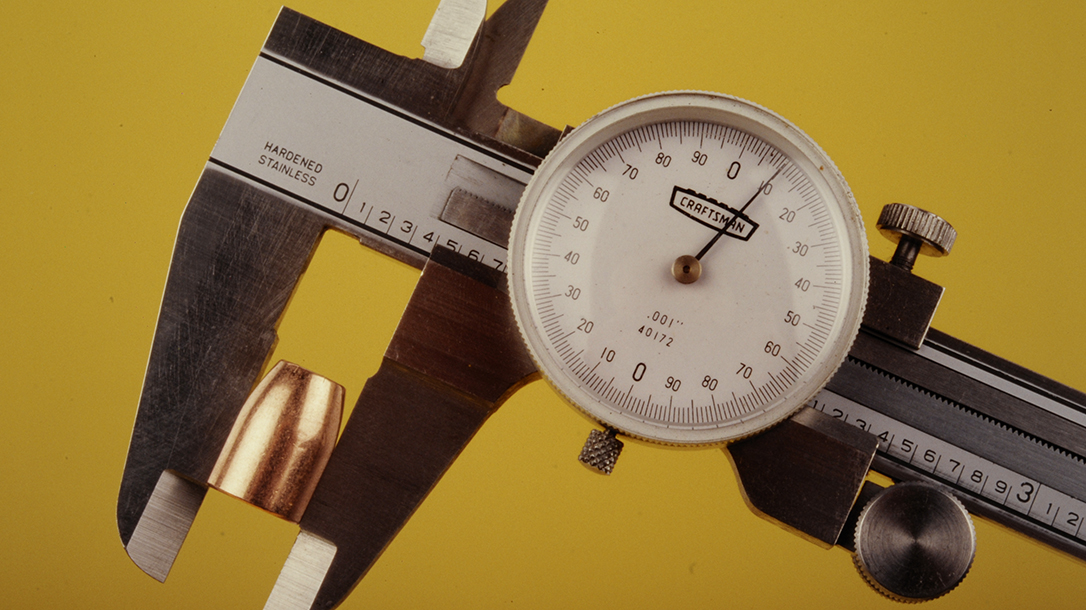

With the gun all cleaned up, I moved to the loading bench. To start out, all of the new cases were first run through the sizing die to clear up any factory defects around the mouths or bodies. They were then fired with a mild charge with a 170-grain bullet, then run through the full-length sizing die again. After cleaning, I checked all the cases for overall length, making sure the trimmed length came to exactly 1.29 inches.

With both the powders and bullets picked for testing, cases were primed, charged and loaded with the appropriate powder for the bullet used in that group. When finishing up, all of the crimping was done as a separate operation. Regardless of the cartridge, I use this method to avoid deforming the bullet tips with the added pressure of pushing the bullet down into the case while crimping or perhaps using a not-so-perfect seating punch. I remove the seating stem after seating all the bullets in one weight category to the cannelure.

Then I adjust the die to either a medium or a heavy crimp, depending on the charge, by running the case up and down into the die. Since the cases are all the same length and the bullets are seated correctly, everything moves along smoothly and in a timely manner.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Range Results

During the testing, and with a wide range of bullets, the results came in true to form for a cartridge of this stature. Using 10.5 grains of Unique, the Sierra 170-grain Jacketed Hollow Cavity bullets produced a group just over 2 inches wide at 25 yards and clocked in at 1,277 fps. With 9.6 grains of Unique, the Speer 200-grain JHPs printed groups around 1.75 inches with a velocity of 1,160 fps. Using 19.6 grains of H110 powder, the Hornady 210-grain JHPs came in at 1,237 fps and produced the best group of the morning at 1.5 inches.

Later, during some advanced testing with the gun secured in a Ransom rest, I managed to create a 0.38-inch group with Hornady silhouette-type bullets over 9.0 grains of Unique powder.

I’ve always had good luck with Remington bullets, and with a good dose of 18.4 grains of Alliant 2400 powder, my groups were in the 2- to 2.25-inch range at 1,241 fps. Using Sierra 210-grain JHPs with 18.9 grains of Alliant 2400 produced similar groups at 1,306 fps. Finally, using heavy 220-grain Speer JSPs gave me 2.5-inch groups at 1,134 fps with 17 grains of Alliant 2400 powder. By the way, using factory ammunition from both Remington and Winchester showed groups averaging about the same as my handloads, and for an interesting fact, velocities recorded over my Oehler Chronograph showed that they were all within 10 to 20 fps of what the companies advertise in their literature.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Hit Or Miss?

Naturally, the question comes up for defensive purposes. Presently, there are no semi-autos chambered for the .41 Magnum, and unless you can find a mint-condition Smith & Wesson Model 57 or a Ruger Redhawk introduced in 1984, you’re stuck with a revolver. While this isn’t a bad thing, it’s not good either in the close confines of your house—but when you look at some of the facts, it may find a spot in the night table beside your bed.

According to Jeff Cooper’s Short Form of stopping power where anything above a 20 earns a passing grade, the .41 Magnum rates a 34.6 on the scale. The .357 Magnum shows up at 19.2, the .45 ACP is a 29.9 and the .44 Magnum of course tops the list at around 41.1. With the .45 ACP and .41 Magnum being so close, you might find a place in your heart for the latter if you can find a handgun for it.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Worthy Addition

Over time, the .41 Magnum has lost a lot of its punch and popularity due to the influx of new and improved cartridges on the playing field. Presently, the number of guns available for it is small. But a recent trip to a local gun show a few weekends ago showed that there are still guns available. It proved if you desire a new dimension in your handloading hobby and shooting experience, look to the .41 Magnum.

So, the question of whether the .41 Magnum is relevant must be answered. To me, the .41 Magnum was a misfit for its use as a law enforcement tool. It’s too big and too powerful, although a few agencies did adapt it for a short period. However, the .41 Magnum, using the right revolver and handload, remains a major hit for the sportsman in the field.

This article is from the January-February 2020 issue of Combat Handguns magazine. Grab your copy at OutdoorGroupStore.com. For digital editions, visit Amazon.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below