The idea of using improvised weapons for personal defense has been around as long as man. In a critical situation, human instinct naturally compels us to grab the closest, sturdiest object and use it to fight for our survival. But due to the events of recent years—particularly the phenomena of active shooters, workplace violence and school shootings—the carry of purpose-designed weapons has become much more restricted. And with that trend, the number of non-permissive environments where weapons are totally forbidden has increased significantly.

History clearly shows that banning weapons has no real effect on stopping violent crimes. Laws only affect the law abiding, so we “good guys” typically only have two choices: Either play by the rules and be vulnerable to violent attacks or break the rules and carry a weapon.

Fortunately, there is a third choice. By understanding how to recognize and use innocuous, everyday objects as improvised weapons, you can bend the rules and ensure that you always have a capable weapon available no matter where you are.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Defending yourself against a committed attack with a purpose-designed weapon is challenging. The less capable your weapon, the tougher that task becomes. With that in mind, the last thing you want to do is to fool yourself into relying on something that doesn’t have a high probability of really hurting your attacker.

The best way to ensure your safety in a street attack is to quickly and decisively disable your attacker. In simple terms, you must hurt him badly enough to make him stop trying to hurt you. Anything that is not a direct route to achieving this goal is a waste of time, so skip the cheesy MacGyver tricks. Concentrate on finding and carrying things that you can grab at a moment’s notice and swing with full force to create fight-stopping damage. You must also make sure that whatever you grab does not do more harm to you than the bad guy.

Into The Action

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Another critical aspect of using improvised weapons in self-defense is actually investing the time and energy to develop real defensive skills. Thinking about stabbing someone with a pen isn’t enough; you need to actually practice the skills of doing through challenging, realistic training. Your training should emphasize simple gross-motor-skill body mechanics that are practical for critical incidents and common to the application of a variety of improvised weapons. Learn these skills well and practice regularly so you can really rely on them when you need them.

RELATED STORY: 10 Everyday Weapons to Use for Self Defense

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

You must also accept the fact that improvised-weapon tactics alone may not be enough to end a fight. A few well-placed stabs with a ballpoint pen will certainly leave a lasting impression, however they are not guaranteed to make him stop. By using pen tactics to create an opportunity for a true disabling strike—like a low-line kick to the knee or ankle—you have a much more reliable and effective defensive skill set. And, again, you’ve separated the reality of effective personal-defense tactics from misguided myth and misinformation.

In my practice and teaching of improvised weapon use, I separate them into three basic categories:

Prepared Weapons: Items that in their basic form are not capable weapons, but with a little preparation can have weapon potential. For example, a magazine by itself won’t do much, but rolled tightly it can be a potent weapon.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Weapons Of Opportunity: Items that you find in your environment that can be adapted to weapon use, like a rock, a beer bottle, a mop or a trash can lid.

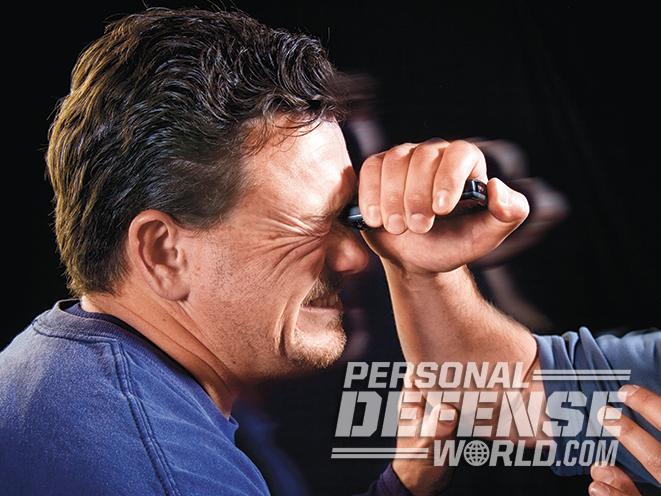

Personal Carry Items: Items that you can easily carry on your person that can be used as weapons, like a flashlight or a ballpoint pen.

Weapon Attributes

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

All serious students of self-defense know that awareness is a key component of a good personal-defense plan. When most people think of awareness, they think of color-code systems, Condition Yellow and looking for signs of unusual activity that could represent potential threats.

All of these aspects of awareness are correct, but real awareness goes much deeper than that. It should include things like assessing your footing and your ability to move quickly, consciousness of obstacles, cover and concealment, mental planning of escape routes and, very importantly, consciousness of potential improvised weapons in your environment.

RELATED STORY: Self-Defense Realities – Justified vs. Excessive Force

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Many things can qualify as improvised weapons, but the best objects are those that share a number of common attributes. By learning to identify these attributes—and objects that possess them—and spot them as you move through different environments, you’ll greatly expand your defensive options. The attributes that make a good improvised weapon include:

Structural Integrity: The object must have the integrity to stand up to full-power impact. If it doesn’t, you must recognize that limitation and be prepared to back it up with something else.

Stopping Power: Objects that are too light don’t hit very hard. Very heavy objects cannot be wielded with speed. If possible, look for something that offers a happy medium.

Immediate Access: Violent situations happen quickly and very suddenly. Focus on things that you can grab and use very quickly.

Versatility: Some objects can be used to strike and block. The more the tool can do, the better it will serve you.

While developing your understanding of weapon attributes, you should also be aware of the basic categories of weapons based on the types of damage they can be used to inflict and the types of functions they can perform. These categories include: impact weapons for striking and creating blunt trauma, edged weapons for cutting or hacking, pointed items for puncturing, flexible items for whipping, entangling and possibly striking, shielding options and multi-functional items that can provide two or more functions.

Full Force

Using an improvised weapon effectively begins with a proper grip. A good grip allows you to strike with full force while managing impact shock and protecting your hand from injury. The three basic grips I teach for improvised weapon use are:

Hammer Grip: Gripping the weapon in your fist like a hammer. This can be used for both small “fist load” weapons and larger stick-like weapons.

Index-Finger Grip: Bracing the weapon against your palm and extending your index finger along the length of the weapon. This works well for weapons like pens and allows striking with great accuracy.

Palm Grip: Gripping the object in the palm of your hand, like a ball. This is best for objects that don’t fit the fully closed fist, like rocks, ash trays and beer mugs.

RELATED STORY: Massad Ayoob – 5 Cases Where You Should Settle or Plea Bargain

During the stress of a violent encounter, people typically revert to instinct. When it comes to body mechanics, they will most often lead with their weak hand—trying to grab and control with it if possible—while striking with forehand or overhand gross-motor-skill blows with their strong hand. Backhand blows, though less common, usually consist of backhand hammerfist strikes.

Since this is what we will naturally do under stress, it is also the best template for a simple, foolproof skill set—at least for one-handed weapons. Known as “cycling” when performed empty handed (a term borrowed from my friend Kelly McCann), it is a dead-simple method of employing most improvised weapons.

Assuming you’re right-handed, start with your left hand and foot forward. Your left palm should be facing forward and your right hand and weapon at about shoulder level. Extend your left palm straight forward without any wind up and touch your intended target. That touch tells your brain exactly where that target is in space. Now, with an elliptical motion of your right hand (as if throwing a ball), strike with the portion of your weapon that extends from the little-finger side of your hand.

After making impact, strike or push again with your left palm as you retract your right hand and chamber it to strike again. Repeat the entire sequence over and over until you develop a smooth, powerful, elliptical flow with both hands.

In general terms, you will use the palm of your left hand to jab, block, check and move your attacker’s limbs out of the way to create openings. The natural “hammering” motion of your right hand enables you to strike hard, fast and accurately at exposed targets. If you’re a lefty, just do the mirror image of what’s explained here.

What do you hit? In general, use hard objects to hit hard things, like the nose, cheekbones, temples, collarbones, sternum, elbows and hands. Pointy objects are best applied to soft, vital targets, like the eyes, neck and jugular notch, armpits and other “tender bits.” They can also be targeted at the hands—especially the backs of the hands—to take them out of the fight. If your pointed object penetrates the skin and gets stuck in the target, the pushing or hitting of the left palm that should immediately follow it will allow you to dislodge the weapon and go back to work.

Unless you’ve landed a really telling blow—like a thrust to the eye—after you’ve struck a few times, your attacker will try to protect himself and spoil your aim. At that point, switch gears and deliver a low-line kick to the shin, ankle or knee. The inside of the ankle is particularly favored, since a simple soccer-style kick will roll the ankle painfully, possibly breaking the tibia and almost certainly disabling him so you can get away.

This tactic is extremely important in that it becomes your real source of stopping power. As mentioned previously, the less capable your weapon, the harder it is to physically disable an attacker with it. Rather than trying to finish the fight with a salt shaker or a ballpoint pen, use that object to deliver some telling, possibly debilitating blows that will force your attacker to raise his hands to protect himself. Then, as soon as the opportunity presents itself, deliver a powerful low-line kick to destroy his mobility and create what you really want: an opportunity to escape.

Training to deliver this low-line kick should be an integral part of your improvised-weapons practice. A good way to do this is to roll up a rubber-backed rug or a bamboo area mat and tape it with duct tape to create a resilient “leg.” Have a partner hold it and practice “kicking and sticking” to dump your entire body weight into the blow.

This same target also makes a handy tool for practicing strikes with various improvised weapons. Taking the time to actually hit something with your tactical pen, flashlight and a variety of common objects that you might find in your environment is critical because it allows you to actually feel what it’s like to hit.

This experience will not only help you develop skill, accuracy and the confidence to use the tactic in a fight, it also helps you find “hot spots” on various objects—protruding surfaces that might do you more harm than good. Finding this out now is much better than disabling your own hand in the middle of a critical incident.

24/7 Defense

Even if you do carry a purpose-designed weapon, improvised weapons can be a great adjunct to your tactics. Make a habit of having a pen, flashlight or other improvised weapon in your hand and ready to go when you’re out on the street. In this way, you can literally walk down the street “armed” without raising any eyebrows. If a situation does arise, use the improvised weapon as a line of first defense and then use the time and distance you’ve created to transition to your purpose-designed weapon.