The grassy hills overlooking the Little Bighorn River spread out before them. It was a typically hot June day in Montana. As Custer’s 7th Cavalry neared the sprawling Indian village, the first hidden warriors rose up, weapons in hand, well prepared to repel the advancing soldiers. It was at this moment that Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer surely realized too late the trap into which he had led. The end was only a matter of time for him and his men. The ensuing battle between Custer’s forces and a massive encampment of Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors would result in the annihilation of Custer’s immediate command and spark far-reaching shockwaves throughout the nation.

Custer’s Fate at the Battle of Little Bighorn

Custer had risen to prominence during the Civil War, earning a reputation as a bold and aggressive cavalry officer. He led from the front, many times avoiding death in numerous battles by sheer luck. In the years after the war, he was dispatched to the Great Plains to forcibly remove Native Americans from their ancestral lands and corral them onto the reservations set up by the government. His tactics and treatment of these indigenous communities galvanized his image among many white Americans as an icon of frontier conquest and Manifest Destiny. Custer was a hero back East.

Tensions between the U.S. government and the Plains tribes reached new heights in early 1876. Demands that the Lakota and Cheyenne fully submit to reservation life were met with resistance, as increasing numbers left the reservations to join the camps of Sitting Bull and other leaders near the Little Bighorn River. Alarmed, military leaders ordered Custer and the 7th Cavalry to depart from Fort Abraham Lincoln in the Dakota Territory and force the bands of Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, and their allies back onto the reservations.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

On June 25, 1876, Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer led elements of the 7th Cavalry Regiment into a clash that would end in catastrophe along the banks of the Little Bighorn River in present-day Montana. The Battle of the Little Bighorn, now erroneously known as “Custer’s Last Stand,” marked a pivotal moment in the conflicts between Native Americans and white settlers in the late 19th century American West.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The Battle of Little Bighorn Begins

Approaching the Little Bighorn valley, Custer’s scouts reported a sprawling village with thousands of Indians camped along the riverbanks. Determined to attack before the Indians could disperse, Custer divided his force of over 600 men into four groups. He led one battalion straight into the heart of the encampment, planning to take the village by surprise and trap the Indians between converging columns. However, he had severely underestimated both the size of the village and the ferocity of Lakota and Cheyenne resistance.

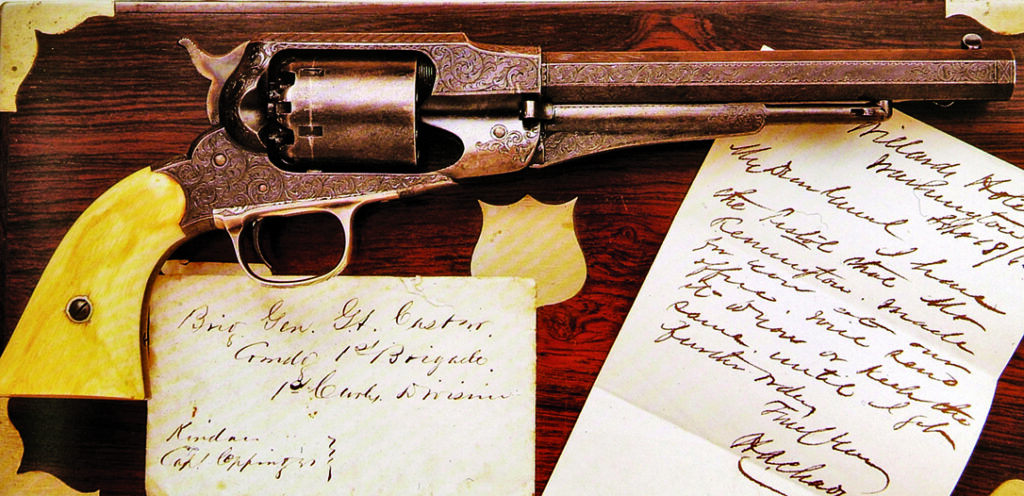

Riding forward into the attack, Custer’s men were swiftly engulfed in a swirling melee as hundreds of Native American warriors counterattacked. Lakota and Cheyenne defenders surrounded the cavalrymen, pouring unrelenting fire into their ranks. The Sioux and Cheyenne warriors attacked with Winchester, Henry, and Spencer repeating rifles as well as bows and arrows. Most of Custer’s men were armed with Springfield single-shot carbine rifles and Colt .45 revolvers; they were easily outgunned.

As the battle raged on, the troopers’ numbers rapidly dwindled under the fierce onslaught, as wave after wave of Lakota and Cheyenne attacked. The few soldiers still standing tightly clenched their rifles, scarcely having time to reload, decided that a general retreat to safety would be their best option. The deafening roar of gunfire mixed with war cries and screams of the dying, as the Americans fought a running battle across the ridge now known as Last Stand Hill. Arrows pierced men and horses as Lakota warriors rushed in close, swinging war clubs and knives in close combat. Custer drew his saber, slashing fiercely as the enemy pressed in.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Fight to the End

Lakota and Cheyenne fighters charged from all sides. Custer rallied his dwindling troopers, exhorting them to stand fast atop Last Stand Hill. Braving a maelstrom of bullets and arrows, they formed a desperate circle, using dead horses as improvised barricades. Custer hurried among his men, firing his revolvers as bullets and arrows whizzed perilously close. His red neckerchief made him an obvious target.

The end for Custer and his battalion was abrupt amid the turmoil of battle. Finding himself surrounded with no route for escape, Custer was killed along with every soldier under his command. According to reports, Custer suffered two gunshot wounds, one near his heart and a second in his head. The exact sequence of these injuries and which one proved fatal remains uncertain. Given the chaos in the closing moments, whoever fired the shot that killed the renowned Cavalry leader likely was unaware of the identity of his target. Custer’s body was discovered with those of 40 fellow soldiers, among them his brother and nephew. Dozens of fallen horses were also found strewn across the area that would come to be known as Last Stand Hill. After the battle, numerous Native American combatants laid claim to personally gunning down the famous officer.

Unrelenting Forces

Custer’s storied run of good fortune had at last expired. The stalwart resistance of Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull, Gall and other Lakota and Cheyenne leaders had inflicted a resounding defeat. All told, the 7th Cavalry incurred 268 men killed and 55 more wounded, while Indian losses ranged from 36 to 60 fallen warriors. The bodies recovered from Last Stand Hill bore horrific marks from bullets and arrows, bearing mute testimony to the fierce intensity of the clash.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The Aftermath

The ripple effects of the legendary 1876 battle proved profound. The stunning triumph at Little Bighorn provided the Lakota and Cheyenne a fleeting sense of hope that quickly vanished. Instead, it provoked an overwhelming military response from the government, aimed at subjugating the Plains tribes through relentless force.

Within the Army, recriminations flew harshly scrutinizing Custer’s tactical decisions. Some, like President Ulysses S. Grant, labeled him reckless for attacking early without support. Others argue Custer thought reinforcements were en route and wanted to maintain surprise. The tragedy fueled public animosity toward Native Americans, influencing relations for decades to come.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The Custer Legend

More than a century later, the Battle of the Little Bighorn remains one of the most storied events in the history of the American West. His widow Libbie ardently promoted her husband’s memory, portraying his heroism in an almost mythic light. Her dedication ensured this defeat became immortalized as Custer’s valorous Last Stand, molding his enduring legacy as a fearless leader cut down in his prime.

Because of Libbie’s efforts, Custer passed into legend as a figure of dramatic contradictions: audacious and foolhardy, heroic and arrogant, iconic yet polarizing. The Last Stand mythologized him as a martyr of frontier conquest, obscuring the broader tragedy of America’s westward expansion. Even more than 140 years later, the Battle of the Little Bighorn remains among the most fabled engagements in U.S. military history.

Meanwhile, history marginalized Native American perspectives and experiences for decades. Only recently have more balanced narratives emerged acknowledging the complexities on both sides of the struggle.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Remembering the Fallen

In the aftermath of the battle, the site became a solemn graveyard, with bodies from both sides left exposed on the barren hills overlooking the Little Bighorn River. Eventually, soldiers returned to provide proper military burials for Custer’s men, interring their remains on the battlefield where they had fallen.

Decades later, the creation of the Custer Battlefield National Monument in 1946 honored these soldiers. The protected area centered around the mass grave of the 7th Cavalry troops, with memorials commemorating their sacrifice. This reflected the portrayal of Custer’s Last Stand prevailing in popular culture as a noble but doomed act of bravery and duty in the face of savage foes.

Meanwhile, the Native American dead remained largely forgotten, their resting places unmarked. It was not until the 1990s that tribal representatives succeeded in gaining recognition of the Indian participants. In 1991, an added memorial honored the Native American warriors who fought to defend their way of life along the Little Bighorn River.

This intermingling of memorials reflects changing attitudes, as more balanced and thoughtful interpretations of the battle have emerged. There is recognition that this landmark event in America’s past held tragic consequences for all involved, whether U.S. trooper or Lakota warrior. The national battlefield now serves as a site of reflection and reconciliation, where visitors can pay respects to the fallen on both sides.

Learn more at the National Park Service’s Little Bighorn Battlefield.