A politician is no better than his last speech; a horse, its last race; and a defensive handgun, the ammo it’s loaded with. No matter how modern or customized your defensive handgun is, if it’s not loaded with the right ammo, it could deliver less than satisfactory results. When it comes to defensive handgun ammo, there are three things that must be considered: reliability, recoil and terminal performance—the triad of defensive handgun ammunition. You must find the proper balance between these three elements if you want to maximize your handgun’s stopping potential.

Reliability Issues

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

There is only one level of reliability to accept, and that’s 100 percent. Anything less might leave you holding nothing but an impact weapon. When things go bad, they are generally bad all around. If you’re relying on ammunition that’s only 90-percent reliable in your handgun, expect that 10 percent to show up when you really need the ammo to work. How do you establish that a load is 100-percent reliable in your handgun? Obviously, you have to test it. The question is how many rounds must be fired. It’s doubtful that experts will agree on this, but one thing’s for sure, every time you fire your handgun with a certain load, you are one shot closer to it malfunctioning with that load. Shoot any gun/ammo combination enough and you’ll experience a stoppage. It might be induced by the ammo, the gun or the shooter or even by a combination of all three, but it will come.

RELATED STORY: 14 Top-Notch Self-Defense Ammo Lines

With the understanding that we all live by the dollar bill and that defensive handgun ammunition is not cheap, here is the protocol I follow and suggest when it comes to establishing reliability. I fire 50 rounds while conducting defensive-type drills. If the handgun/ammo combo delivers 100-percent reliability during those drills, I’ll trust that load until it proves otherwise. When I replace my ammo annually, I’ll fire the old ammo under the same conditions. Once I’ve fired 250 rounds without a hiccup, I quit worrying about it altogether.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Here’s another consideration. In gun magazines you’ll see references to torture tests where a handgun is subjected to hundreds of rounds without being cleaned. With regard to carry-gun reliability, this is of no value unless you plan to never clean your gun. Most folks I know generally carry a clean gun or a gun that has only had a magazine or two fired through it since cleaning. When establishing reliability, conduct the evaluation with the gun in the condition you will carry it. When speaking of reliability, there should also be some mention of accuracy because, after all, you need to rely on your ammo to hit what you are shooting at. As important as accuracy is, I can’t think of a single defensive handgun load I’ve tested in the last several years that did not deliver adequate accuracy. Besides, in reality, your handgun and your skill with it will have more bearing on accuracy than the ammunition.

Recoil Matters

Regardless of the handgun you carry, different loads will generate substantially different levels of recoil. Between the common carry calibers, I’ve seen the least variance of recoil with the .40 S&W. For the most part—at least as far as I am concerned—recoil will be very similar, whether you’re using 155- or 180-grain bullets in a .40 S&W. With the .380 ACP, the 9mm and the .45 ACP, it’s a different story mostly because of the wide variety of bullet weights and the +P offerings for each cartridge. The same is true with the .38 Special, the .38 Special +P and the .357 Mag revolvers. A revolver capable of firing all three cartridges will show massive swings in recoil impulse. The amount of recoil impulse is important because it can adversely affect your ability to trigger a fast, well-aimed second shot. Depending on your handgun, shooting skill and strength, the amount of recoil you can control will vary. How do you determine what you can handle? You’ll have to shoot to find out.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Luckily, ammunition manufacturers offer external ballistics data on the ammo they load, which will help you determine the maximum recoil you can handle. Let’s say, for example, you find that you can comfortably shoot Buffalo Bore’s +P+ 9mm 95-grain TAC-XP load out of your Kimber Solo. According to Buffalo Bore, that load has a muzzle energy of about 413 foot-pounds. For all practical purposes, you can shoot any other 9mm load, which generates the same or less muzzle energy with equal control. You can use those energy figures to make comparisons for other guns in other chamberings, too. What you cannot do is compare a load with 400 foot-pounds from your 27-ounce Colt Commander in .45 ACP with a load that generates the same amount of foot-pounds out of your 17-ounce Kimber Solo. The comparison is only valid when looking at different loads fired from the same handgun.

Terminal Performance

The third side of the triad is terminal performance. Terminal performance concerns what the bullet fired from a handgun does when it impacts that goblin trying to beat you senseless with a troll’s leg bone. Terminal performance is itself dependent on three things: bullet design, impact velocity and the target being hit.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

RELATED STORY: 12 Centerfire Loads for Personal Protection & Home Defense

Ideally, you’ll want the bullet to impact with enough velocity to guarantee expansion of about 1.5 times the bullet’s original diameter. There’s a valid argument for non-expanding, hard-cast lead bullets: they penetrate like Neptune’s spear, and those with a flat meplate also damage a reasonable amount of tissue. If penetration of at least 2 feet or more is your idea of a good defensive handgun load, you’ll need a non-expanding bullet, and the hard-cast lead loads from Buffalo Bore are very likely your best option. For those who like bullets to expand so the wound cavity has the widest diameter possible but still offer at least 1 foot of penetration, projection expansion of about 1.5 times is generally optimal.

Though some defensive handgun ammunition is specifically designed to perform this way from short-barreled handguns, most is tested from a 4- or 5-inch barrel. Believe it or not, the velocity loss that can occur from a barrel even just 1 inch shorter can be substantial—enough to deprive that bullet of the velocity it needs to expand. The only way to know for sure if the ammo you have chosen will expand is to test it in gelatin, wet packs of paper or water. You can also consult manufacturer’s information or independent test results and compare your findings with the actual, chronographed velocity of that load from the handgun you plan to use for self-defense.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

As far as bullet design, having tested most of the defensive-handgun bullets currently available, I can tell you that, given enough velocity, most all will provide the necessary expansion and penetrate to at least 1 foot in 10-percent ordnance gelatin. An exception would be most of the .380 ACP and .38 Special loads, which penetrate about 8 to 10 inches on average.

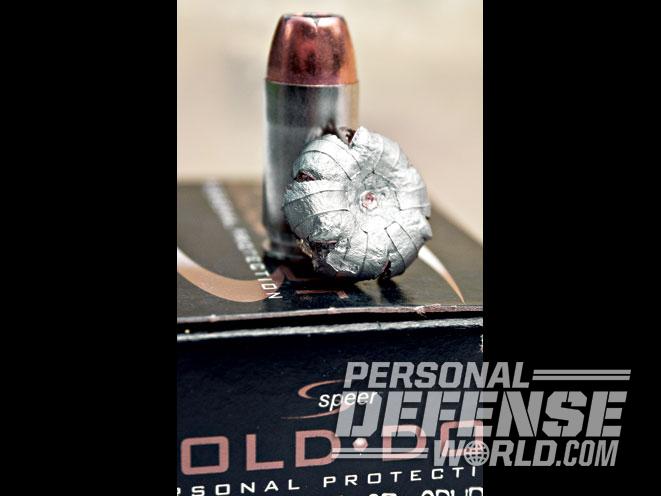

The final consideration is what the bullet will impact. It’s safe for us to make the assumption that most likely your attacker will not be naked. So before bullets can get inside a bad guy to do the necessary damage to stop him, they need to pass through his clothing. Some clothing can turn hollow-point bullets into solids because the clothing fills the hollow-point cavity and the bullet fails to expand. However, this is less common today than it was just 10 years ago. Bullet manufacturers have recognized this possibility and are building bullets that will still expand, regardless of how much or what type of clothing they pass through. The Barnes TAC-XP, Remington Golden Saber, Federal Hydra-Shok and Guard Dog, Speer Gold Dot, Hornady Critical Defense and Critical Duty and Winchester PDX1 bullets have all been engineered with this in mind and do very well even when passing through clothing.

But keep velocity in mind, too. Having to pass through various layers of clothing can slow a bullet even more, and a bullet that expands just fine when impacting a naked test medium or bad guy might fail to expand after being slowed by a leather jacket and a denim shirt.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Making Your Choice

If you’re starting from scratch, I’d suggest you choose a load that utilizes a bullet that’s middle of the road in weight for your cartridge, like, say, 124 grains for a 9mm, 165 grains for a .40 S&W and 185 grains for a .45 ACP. I’d also, at least initially, go with a trusted bullet like the Barnes TAC-XP, Remington Golden Saber or one of the others mentioned above. Keep in mind, some boutique ammo companies like Buffalo Bore load the excellent Speer Gold Dot bullet but identify it only as a “Bonded” bullet on the packaging at Speer’s request. Next, while working through some defensive drills, I’d fire 50 rounds to check reliability and recoil. If the load passes those tests, I’d then mix up a block of 10-percent gelatin and shoot several bullets into the block—some through various layers of clothing—to check expansion and penetration.

RELATED STORY: 6 Hot New Holster & Ammo Products Currently Available

Other than that, the most important thing you can do is become proficient with your handgun. Learn to get it out of the holster and on target fast, and learn to shoot fast and not miss. Practice!