The Colt 1871-72 Open Top was new, innovative and virtually obsolete the day it was introduced!

In Colt’s haste to introduce a new self-contained-cartridge-loading revolver as soon as possible after the expiration of the S&W Rollin White patent, the company chose to build a model based on as many existing parts as possible, and the majority of those parts came from the venerable 1860 Army. To make the Open Top, Colt used 1860 Army frames. They were fitted with an all-new barrel and cylinder designed by Charles B. Richards and William Mason. Both men were not only instrumental in designing the Open Top, but they developed an entire post-Civil-War line of metallic cartridge conversions using up all of Colt’s remaining percussion pistol inventory, from pocket models to the 1860 Army. Mason was Colt’s superintendent of the armory, and in 1872 he designed and patented the now-legendary Peacemaker. But just before that came the Open Top, Colt’s first cartridge-firing six-shooter.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

A Closer Look

At a glance, the Colt Open Top resembles the Richards-Mason 1860 Army conversions fitted with the later solid S-lug (newly manufactured) barrel; it can be quickly distinguished by the integral rear sight cast into the top of the barrel at the breech, and the full-length, non-rebated .44 Henry cylinder.

Since the Colt Open Top was not a conversion, it did not require a conversion ring like the Richards models, as the breech area was machined directly from the recoil shield, making the loading gate a separate assembly that was mounted to the frame by a screw at the base of the gate. The Open Tops utilized both internal and external loading gate spring designs, the latter version noted by the bottom of the spring leaf being screwed to the frame just above the trigger screw. The Open Top loading gate designs were also used on the Richards and Richards-Mason cartridge conversions.

The general configuration of the Colt Open Top frame was the 1860 Army’s, but without the step cut into the frame to accommodate the percussion pistol’s rebated cylinder. All factory-produced Open Tops had 7½-inch barrels, although a number are seen with 5-3/8- or 5½-inch barrel lengths. These were either cut down by their owners or by gunsmiths for retailers who wanted to offer something a little different. Colt, however, only built the Open Top with 7½-inch barrels. Interestingly, most of the parts for the Open Top frame and lock mechanism were also interchangeable with the Richards-Mason 1860 Army conversions, and a Mason-style cartridge ejector was used as well.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Different Versions

Although only produced for a time, there were two versions of the Open Top distinguished principally by the size of their grips. On early models, the shorter 1851 Navy-sized grips were used with brass grip straps, whereas in later production, the heftier 1860 Army stocks were fitted with steel grip straps. This was also true of the Peacemaker.

All Colt Open Top models had “.44 CAL” stamped on the left triggerguard shoulder, and “ADDRESS COL. SAML COLT NEW-YORK U.S. AMERICA” barrel addresses were stamped on all but very late production models. The last examples were stamped “COLT’S PT. F.A. MFG. CO. HARTFORD. CT. U.S.A.” And all Open Top pistols also had the two-line “COLTS PATENT” stamp on the left side of the frame.

In 1871 the U.S. Ordnance Department was considering the cartridge-loading Open Top as a replacement for its Civil-War-era revolvers but decided against it, which compelled Colt to abandon its long-established separate barrel and frame design and develop a solid-frame model along the lines of Remington models used during that war.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

As the late Colt historian and author R. L. Wilson noted in The Book of Colt Firearms: “Bearing in mind the rejection of the Open Top by the U.S. Ordnance Department, Colt’s engineers, particularly William Mason, worked feverishly to develop the successor to the Open Top … The Single Action Army was a natural evolution by combination of the best design features of the percussion, conversion and Open Top models with the necessary alterations dictated by military needs and the properties of the metallic cartridge ammunition. In 1872, the Colt Peacemaker was adopted by the U.S. Army, following a vigorous and highly competitive series of tests.”

The Open Top’s fate was sealed.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The Colt Open Top’s Demise

The Rollin White patent for the bored-through, breech-loading cylinder had hobbled Colt since 1855, and while the patent was also being vigorously enforced by Smith & Wesson, Colt’s model room was nevertheless bustling with experimental designs of cartridge-firing models based on existing Colt revolvers. These ranged from .44-caliber Dragoons to .32- and .36-caliber pocket pistols. By 1871, Richards and Mason were also experimenting with several variations of the Open Top, including models chambered for .44 centerfire and .38 rimfire cartridges. The latter variation, often referred to as a “Baby Open Top,” was also put into limited production and assembled on a smaller frame—about the size of an 1862 Police or 1865 Pocket Model of Navy Caliber pistol.

Although William Mason and Charles B. Richards built quite a few experimental Open Tops, the only example put into full production was chambered for .44 Henry rimfire cartridges, and there was a good rationale for this decision. There were thousands of Henry rifles in use, thus Colt had decided upon a revolver that could share its ammunition with the Henry—the same rationale that would lead Winchester to build lever-action rifles chambered for the same centerfire cartridges as Colt revolvers.

While this appears to be logical in retrospect, it becomes somewhat paradoxical, since less than a year later, Colt had Richards 1860 Army conversions available in .44 centerfire, a cartridge that was preferred over the .44 Henry rimfire by the U.S. military. Despite the availability of Henry ammunition, the Open Top was out of production by the summer of 1873, whereas the .44 centerfire Richards and Richards-Mason Army conversions, which were purchased by the military, would remain in production until 1878. The Open Top then was the only production casualty of Colt’s early cartridge conversion era.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

End Of The Road

The Open Top’s undoing was in not being chambered for the new .44 centerfire cartridge, which had in fact been designed by Colt and introduced in 1871, a year after Smith & Wesson developed and introduced the .44 S&W Russian for its new No. 3 American top-break revolver. S&W’s proprietary .44 Russian was a shorter cartridge than Colt’s .44-caliber centerfire round. Like the Colt, in the first years after the Civil War, Smith & Wesson was also actively pursuing U.S. military contracts, and Daniel B. Wesson and Horace Smith had wisely hedged their bet by also offering the No. 3 American chambered for the .44 Henry rimfire. Consequently, Colt had been outgunned by S&W once again, but only for a year. The Mason-designed Single Action Army turned the tables in Colt’s favor once again with its slightly more powerful .44 centerfire round.

In addition, in 1875, Colt also added the .45 Long Colt to the Peacemaker’s chamberings, while S&W unveiled its new .45 Schofield round for the improved Schofield top-break revolver. But this time Colt had the clear advantage. While the shorter .45 S&W Schofield cartridge could be used in a Peacemaker, the .45 Long Colt would not fit the Schofield’s shorter cylinder, and thus, in 1875, Colt became the clear victor over Smith & Wesson in the battle for a long-term military contract; the .45 Colt Peacemaker was adopted as the standard-issue sidearm of the U.S. cavalry. In the midst of all this, the Colt 1871-72 Open Tops also simply became obsolete. Even so, the .44 Henry rimfire did not. The number of rifles and pistols still chambered for this cartridge kept the Henry rimfire in production until 1934.

The Open Top’s Reprise

Richards and Mason had chosen to chamber the 1871-72 Open Top for what, in 1871, was the most abundant metallic cartridge available in America: the Civil-War-era .44 Henry rimfire. These .44 rimfire rifle cartridges were manufactured by the tens of thousands, but not everyone was in the military or had the money for a new lever-action rifle, so it made sense to create a revolver that used this ammo.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

As for the Open Top, confusion and misconception have always surrounded it because the guns virtually overlapped with the 1860 Army Richards conversions, even though the Open Top preceded them by a year. In 1872, both the .44 Henry rimfire Open Top and .44 Colt centerfire 1860 Army Richards Type I cartridge conversions were being produced, and the economics of manufacturing simply favored the Army conversions. Colt also had .38-caliber rimfire and centerfire conversions of the 1851 and 1861 Navy. It also had various pocket pistols, all of which would remain in production well into the 1880s, a success by any measure.

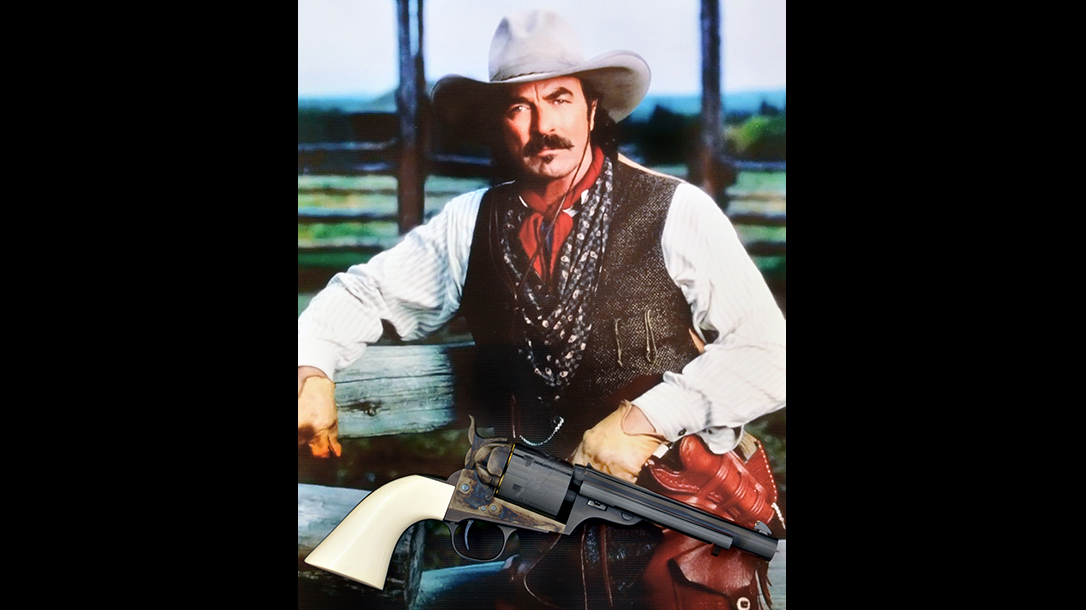

The Colt Open Top did not entirely fade from the story of the American West. The roughly 7,000 built by Colt found their way into the hands of cowboys still armed with Henry rifles, and another chapter of the Old West was written. In addition, Tom Selleck’s classic 2001 Western “Crossfire Trail” also helped keep the Open Top legend alive; the design is so iconic today that Uberti builds an exceptional 1871-72 reproduction sold by Cimarron and Taylor’s & Company Firearms, among others. So, while the Peacemaker may have become the most successful single-action revolver in history, it owes its existence to its short-lived predecessor, the 1871-72 Open Top.

This article was originally published in “Guns of the Old West” summer 2018. To order a copy and subscribe, visit outdoorgroupstore.com.