The old cliche is that the .22 pistol you have on you is better than the .45 you leave at home. The same thing has been said of .380 and other calibers as well. But could you seriously conceal and carry a .22 LR?

It’s more feasible than you might think.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Granted, you probably shouldn’t, which we will get into. There is, however, a body of real-world evidence that either of the popular .22 rimfire rounds — .22 LR and .22 WMR — are more effective than one believes at first glance. If you had to conceal carry a .22 LR pistol, it wouldn’t be the worst thing in the world.

What Stops An Attacker?

Ballistic gel tests are fun, but they aren’t the best predictor of whether a bullet is going to be effective on a live target. They indicate that they might be effective, but don’t guarantee that they will. How so?

First, most people who receive a wound from a handgun survive. Studies and surveys vary, but it’s commonly held to be more than 80 percent. We can therefore infer that 9mm, or any other popular round, is necessarily Death and Destruction personified. What causes people to stop, though?

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Physical trauma or psychological shock. Trauma that stops a person must be to either the brain stem or the musculoskeletal system; the knees, pelvis and spine are sure stops if sufficient trauma can be delivered. Wounds to the vital organs can take far too long to really take effect; most of the time, a person stops because of shock and damage to vital organs takes effect after they drop. Ballistic gelatin doesn’t really indicate a bullet’s capacity to do anything other than penetrate and expand in flesh.

A .22 LR or .22 Magnum is not capable of sufficient musculoskeletal trauma, so that’s a non-starter. But what about the other parts? Well, if you can hit a banana with a .22 LR, you can hit the brainstem, so that works. As far as the shock required to make a person stop, that depends on how the person reacts, which can’t be anticipated.

In other words, stopping a person requires either accurate and precise fire, or the target deciding they don’t want to fight anymore. As to the former, the .22 LR is certainly capable. The latter is completely irrespective of caliber. Thus, the .22 LR is actually a viable defensive round.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

.22 LR In the Real World

An informal study by Greg Ellifritz with Buckeye State Firearms looked at what information was available as far as caliber of a firearm involved in a defensive shooting. Ellifritz looked at 10 years of data about what caliber of gun was used by a civilian, police officer or soldier in stopping a threat.

As it turned out, there were 154 shootings involving a .22 LR. Of those, 31 percent were one-shot stops; the attacker was stopped or incapacitated with one round. 60 percent of attackers that were stopped with any number of rounds were incapacitated with round to the torso or head. 34 percent of shootings with .22 LR—or .22 Short or .22 Long—were fatal. On average, only 1.4 rounds were needed on average to end the engagement.

But what about a full-size round?

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

9x19mm achieved a one-shot stop 34 percent of the time, with 47 percent of attackers being stopped with a hit to the head or torso. Only 24 percent of shootings were fatal; an average 2.36 rounds were needed to end the engagement.

Bella Twin

Still not convinced? Consider the story of Bella Twin. Twin, according to The Truth About Guns, shot and killed a grizzly bear in the early 1950s near Slave Lake in Alberta with a single-shot .22 Long—not even Long Rifle, .22 Long, which is actually weaker. Granted, Twin—then in her 60s—was a lifelong subsistence hunter and trapper, so she knew where to put it. When the bear approached Twin and her hunting partner, she knew it wasn’t going away and waited until she saw the side of the head.

The bear dropped like a bag of bricks with the first shot. It was estimated to be at least nine feet in length and likely weighed in the neighborhood of 1,000 pounds. The skull scored a 26 7/16, then a Boone and Crockett record.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

If it can do for a grizzly, it can do for a man.

You Shouldn’t Pack a Concealed Carry 22

Why shouldn’t you conceal and carry a .22, then?

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

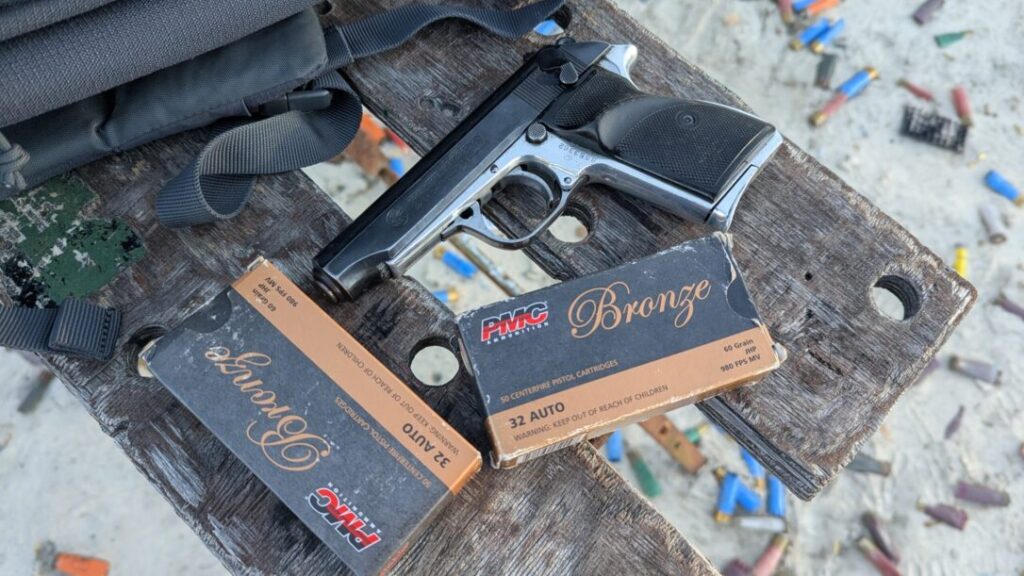

Well, traditional handgun rounds for self-defense became popular because they tended to work more than the ones that no one uses anymore. Nobody carries a .32 Long Colt. Know why? .38 Special worked better! The same goes for .32-20 and .38-40.

Elmer Keith became convinced of the merits of bigger bullets when his .25-35 failed to bring down an average-sized doe. He traded it in for a Trapdoor Springfield in .45-70 and never had the same problem again. There’s something to be said for the idea.

The aforementioned study also revealed something else, though. The .22 rimfire rounds failed to stop an attacker 31 percent of the time. 9mm, by contrast, had a failure rate of only 13 percent. Should you be curious, there was a standout one-shot stopper among the handgun rounds: .44 Magnum, with a 59 percent one-shot stop rate. However, it had the same failure to stop rate as 9mm.

None of the popular semi-auto rounds — 9mm, .40 and .45 ACP — differed by more than 10 percent in any category of performance. The only one to really stand out in any category was .40 S&W, with a 45 percent one-shot stop rate.

Most people who carry a gun every day do so with one of five calibers: .380, 9mm, .40 S&W, .38 Special, .357 Magnum and .45 ACP. Yes, there are some 10mm and .357 Sig people, but most people carry one of the aforementioned five. Those rounds were found to be more or less similar, with only marginal differences. In other words, they work and do so reliably when the shooter does their job, and — it must be said — did so better than .22 LR.

If .22 LR was the best “man-stopper,” everyone would carry it. So the thing is you could if you wanted or had to, and it could actually work. But it’s better if you carry one of the traditional carry rounds for self-protection.

About the author: Sam Hoober is a contributing editor for Alien Gear Holsters, a subsidiary of Tedder Industries.