Despite what you might’ve heard, concealed carry guns have always been top sellers—not only today, but they also took high honors some 167 years ago. Although small, mostly single-shot pistols had been around for a few centuries, it took the percussion cap and Samuel Colt’s inventive mind to come up with a truly practical and concealable repeating handgun.

Early Colt’s

From 1836 to 1842, Colt produced his Paterson revolvers and some, such as the No. 1 Baby or No. 2 Belt Model, were in .28 and .31 caliber and could be had with a barrel as short as 1.75 inches. Unfortunately, Colt’s company went under, but it was resurrected in 1847 during the Mexican-American War, when Colt introduced the huge .44 Walker revolver and then the Dragoon models for the military.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Samuel Colt, a visionary for his time, saw a market for a small revolver to sell to civilians and scaled down the Dragoon in both size and caliber (.31) and called it the “Baby Dragoon.” The next year saw the introduction of the 1849 Pocket Model that was another .31, but it could be had with a five- or six-shot cylinder. This became Colt’s big seller, with 325,000 made. The most popular barrel length was 3 inches, making it easy to hide.

S&W Origins

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Smith & Wesson started out with a somewhat strange and under-powered lever-action handgun, but what really put the company on the map was the launch of a tiny, 10-ounce, seven-shot revolver in 1858 that fired a revolutionary .22-caliber, self-contained metallic cartridge.

Called the Model 1, it fired a round much like today’s .22 Short rimfire and normally came with a 3.19-inch barrel. S&W sold all it could make, and the Civil War prompted a call for a larger .32 rimfire revolver. The six-shot Model 2 Army came out in 1861 chambered in .32 Long with a 5- or 6-inch barrel. The larger caliber was appreciated, but many wanted it in a smaller package, so in 1865 S&W came out with the Model 1½, a five-shooter that could chamber .32 Short or Long rimfire cartridges and came standard with a 3-inch barrel. Supply never caught up with demand.

S&W already had the rights to the Rollin White patent for the bored-through cylinder, but the company spent a lot of money and effort in the 1860s acquiring patent rights on various inventions that would enable S&W to make a big-bore revolver with a hinged frame. The tip-up frames on the .22 and .32 revolvers were not strong enough, but the hinged frame allowed the production in May 1870 of a .44-caliber sixgun. The Model 3 didn’t garner the U.S. military sales S&W hoped for—although the company did sell a modified version to Czarist Russia. So S&W again turned to the civilian market and, using the Model 3 design, came out with the Single Action .38 in March of 1876. It chambered the new .38 S&W cartridge and had a five-shot capacity as well as a spur trigger. A smaller and improved model in .32 S&W appeared in January of 1878.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

S&W never rested on its laurels and in January of 1880 announced a hinged-frame, double-action .38. Versions were available with 3.25-, 4- and 5-inch barrels, and S&W improved this series until it reached the Perfected Model, which was made until 1920. In 1880, a double-action .32 came onto the scene, but one of the most popular versions, the Safety Hammerless came out in May of 1884. Its concealed hammer and grip safety spawned the “Lemon-Squeezer” moniker.

New Century

Revolvers in .32 and .38 caliber proliferated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with millions being manufactured by companies like Iver Johnson, Harrington & Richardson, Hopkins & Allen, Merwin & Hulbert and others, plus a host of foreign knock-offs. These diminutive revolvers filled a lot of pockets for the better part of 70 years along with various derringers from Colt, Remington and Sharps.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The hinged-frame revolvers had a lot of good features, principally their simultaneous ejection of brass and easy reloading with the exposed cylinder breech. The negative side was the strength of the lockup, which relegated them to low/medium-powered cartridges. Colt made a pocket-sized double-action .38, the Lightning, which followed the design of the Single Action Army but was just as slow to unload/reload. Then, in 1889, Colt introduced the first revolver with a swing-out cylinder, beginning a whole new era in wheelgun design. It began life as the New Navy in .38 Long Colt and later was improved and adopted by the Army in 1892. With healthy sales figures, this medium-frame sixgun could also be had in .41 Long Colt with a barrel as short as 2 inches.

Colt was the first gun-maker to produce a small-frame, swing-out-cylinder double action that it called the New Pocket in 1893. This was a six-shot .32 with a barrel starting at 2.5 inches, and some 30,000 were made before it was replaced with the safer-to-carry Pocket Positive in 1905. A more police-oriented .32 called the “New Police” was released in 1896 and became standard issue for the NYPD under Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt. The year 1905 also saw the introduction of the “Police Positive,” which was a six-shot .38 that Colt renamed the “New Police.” A short-barreled version was called the “Banker’s Special.”

S&W entered the swing-out-cylinder revolver market with the Hand Ejector model in 1896. This small I-Frame took a new .32 S&W Long cartridge. It was adopted by the Philadelphia Police Department and could be had with a 3.25-inch barrel. Some design weaknesses were corrected, and it became the .32 Hand Ejector Model of 1903—the first S&W double action to have the locking lug on the underside of the barrel. This Hand Ejector spawned the Regulation Police .32 in March of 1917, and it had a longer grip for uniform police use. It was followed by a similar gun with a five-shot, .38-caliber cylinder. This .38 cylinder on a .32 frame was also known as the .38/32, and in 1936 popular demand dictated a 2-inch-barreled, round-butt version named the “.38/32 Terrier.”

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Today, these small .32 and .38 revolvers would be classified as “mouse guns,” but back in the day they were considered adequate for their roles in law enforcement and self-defense.

The First Semi-Autos

The 1890s ushered in the dawn of the semi-automatic pistol as smokeless-powder cartridges became the norm. Most early designs were large handguns for military use, but American arms inventor John Moses Browning went to FN in Belgium with a design that became the Model 1900 in 7.65mm Browning Short (.32 ACP), a cartridge he’d invented. It was an odd-looking single-action pistol but was relatively flat, and its box magazine held seven cartridges. It was another gun favored by President Theodore Roosevelt.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Colt teamed up with Browning for an improved .32-caliber pistol known as the Model 1903 Pocket Hammerless (a misnomer, as it had a concealed hammer), and it was a slim, sleek pistol with a 3.75- or 4-inch barrel and an 8+1 capacity. It immediately became popular for self-defense and as a gun for plainclothes officers and detectives. It was also adopted by the U.S. military as a “General Officer’s Pistol,” and 572,215 were made over 42 years. A .380 ACP version called the Model 1908 Pocket Hammerless was also popular and adopted by the Shanghai Police. Another introduction that year was the .25-caliber Colt Model 1908 Vest Pocket, which became Colt’s third most popular autoloader behind the Model 1911 and the Model 1903.

Other small semi-auto pistols came onto the scene to compete for a market share. A real “Art Deco” design was the Savage Model 1907 in .32 ACP, and its claim to fame was a 10-round magazine and a cocking lever that looked like an exposed hammer. It had a single-action mechanism and was endorsed by such notaries as Buffalo Bill, Bat Masterson and William Pinkerton. A .380 ACP version came along in 1920.

S&W enter the small semi-auto fray with the Model 1913 in .35 S&W, a cartridge developed in cooperation with Remington. It was a single action with a grip safety incorporated into the frontstrap, but its odd appearance and cartridge resulted in it being discontinued in 1922. In 1924, a more streamlined version in .32 ACP was offered, but it retailed at $11 more than a Colt Model 1903, and production declined to nothing in 1929.

Specials & Magnums

In 1899, S&W released its K-Frame .38 Hand Ejector, which became known as the “Military & Police.” This revolver, later designated the Model 10, was S&W’s most famous revolver and ended up being synonymous with the term “Police Special.” The new sixgun was also coupled with a new cartridge, the .38 Special, which had improved ballistics over the .38 Colt, with a slightly heavier bullet and powder charge. As the Prohibition took hold in America, cartridges like the .32 and .38 S&W fell out of favor. The K-Frame M&P was not a pocket gun, even with a 2-inch barrel and a round butt. The FBI issued the tapered 4-inch-barreled version, but it was a belt holster proposition.

Colt jumped on the bandwagon in 1908 with its new Police Positive Special. It had all the attributes of the Police Positive, but with a longer cylinder so it could chamber the more powerful .38 Special. It was the lightest and most compact revolver out in .38 Special and had a square-butt grip frame. It could be ordered with a barrel as short as 1.75 inches.

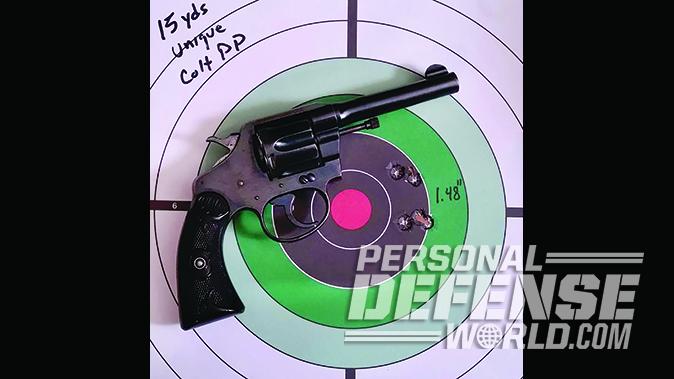

Colt had a penchant for short-barreled wheelguns dating back to the Baby Paterson, and the popularity of the Police Positive Special led to a 2-inch-barreled revolver with a round-butt grip frame in .38 Special—the Detective Special. This small six-shooter really took off and became a favorite with police and armed citizens alike. It wasn’t much bigger than the S&W Terrier, but it carried six rounds of .38 Special instead of five rounds of .38 S&W cartridges. It was smaller and lighter but had the same cartridge capacity as the 2-inch-barreled M&P.

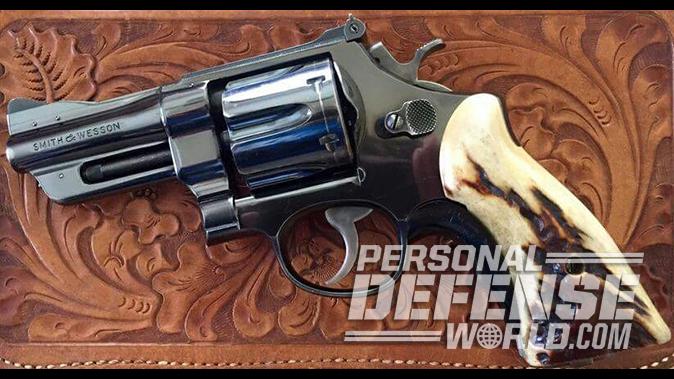

The “Gangster Era” spawned another popular cartridge and a revolver to go with it. Police complained that the .38 Special, even in the heavy-duty .38-44 load, was not powerful enough to punch through the car bodies of bootleggers and motorized crooks like Bonnie and Clyde. So, in 1935, S&W rolled out a big N-Frame revolver chambered for the new .357 Magnum that the company had developed with Winchester. It was at first a special-order proposition and became known as the “Registered Magnum.” It fired a bullet of the same weight as the .38 Special but at much higher velocities, and a metal-piecing load was also made. S&W presented a .357 Magnum to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, and the big sixgun became popular with agents, as it could be had with a 3.5-inch barrel to aid in concealment. Its popularity resulted in its being made a standard-production item and later was designated the Model 27.

Civilian gun manufacturing slumped during WWII, and arms-makers took their time getting production lines rolling again after the war. S&W was still looking for a small revolver to better compete with Colt’s Detective Special and took the I-Frame of the Terrier and stretched it to accommodate a longer cylinder. Thus, the J-Frame was born. It was a five-shot .38 Special with a 2-inch barrel. S&W took it to the International Association of Chiefs of Police Convention in 1950 for its debut and asked the police chiefs in attendance to give it a name. The new snubbie was christened the “Chief’s Special” before becoming known as the Model 36 a few years later. S&W still offers it today.

Reliable Concealed Carry Guns

Compared to what we have now, the concealed carry guns of yesteryear might seem inadequate. They were generally all steel, making them heavie. They also weren’t as ergonomically designed and the sights were often tiny and difficult to see clearly. Ammunition has also improved exponentially, with hollow-point bullet designs and improved gunpowder making old cartridges like the .32 or .38 S&W obsolete. But these guns still managed to do their jobs in the right hands with proper bullet placement, which is still more often than not the deciding factor rather than gun design or cartridge efficiency. Many of these guns still see service today. Don’t be too surprised if you should see a Savage Model 1907 or Colt Detective Special riding on my hip.

This article was originally published in “Concealed Carry Handguns” 2017. To order a copy, visit outdoorgroupstore.com.