Years ago, I’d seen Japanese battle rifles at gun shows and in the closet of my good friend Dexter Thunder, whose father boasted a captured “Jap 31.”

In the spring of 1963, I had two American high-powered rifles and an interest in World War II history. Then I got the call from my brother. I was to be a consultant, properties master, acquisitions manager and weapons guy on an amateur WWII film project beginning the next year. Uh oh. I had to learn more. So I read every word I could find. Fortunately, my next-door neighbor, Bill Flanagan, had a large collection of those rifles and knew a lot about them and their unique qualities.

I quickly discovered Masami Tokoi of Tokyo and several others. The venture set a course that leads here. The story of Japanese battle rifles from 1905 to 1945 is brilliant and tangled. Inhibited by a chronic lack of automatic weapons, especially submachine guns, Japanese soldiers tried to accomplish a lot that proved impossible. From 1906 to 1945, Japanese factories produced about 6.4 million rifles. It’s worth noting that Japanese bolt-action rifles are often discussed as one entity, which they aren’t. And to some Japanese contacts, only the Type 38, the earlier of the contemporary rifles, is truly an “Arisaka.”

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Japanese model designations are based on the reign of emperors and the establishment of royal lines. After about 1930, the last two digits of the Japanese calendar year were used. Our 1939 was Japanese year 2599, and therefore, the new 7.7mm rifle became the Type 99. The earlier system used the anniversary of the reigning monarch, so the old Type 38 marked the 38th year of the Meiji era (or 1905 to the West).

Into The Next Century

Japan had been a feudal state well into the 19th century. But by 1897, Japan’s military societies understood the need to upgrade to the standards of Europeans, and they adopted a Mauser derivative repeating rifle called the Type 30, which was designed by Col. Nariakira Arisaka’s Ordnance Research Commission.

Mauser’s Gewehr 98 appeared almost immediately thereafter, and Japanese studies quickly recommended adopting the new safety and strength features of the upgraded German system. The overwhelming concern of the new setup was the security of the receiver in case cartridges failed catastrophically.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The Type 38 (made in 1905) forms its receiver from a robust, round steel forging of continuous diameter. No collar is used in the receiver proper, instead forming this surface as part of the breech end of the barrel, which comprises a massive shroud for the nose of the bolt.

Locking shoulders at the rear of the receiver ring are beveled on their forward corners, so closing the bolt draws that mechanism forcibly forward. The left receiver wall remains high, unperforated and extremely sturdy. As with standard Mausers, the bolt is substantial, one piece and bored from the rear, placing a solid face against the cartridge. The bolt and receiver are relieved in unique ways.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Rather than a separate safety, Arisakas use a huge cup-like striker cap, activated (with the safety off) by pressing firmly forward and turning it about clockwise.

Because of wood weaknesses, with stocks tending to break at the wrist near the pistol grip, the forward portion wraps around the pistol grip, holding the second slab of the buttstock heel together. Despite porous woods, they experienced little breakage in that area. The venting of bolt areas and holes in the receivers of Japanese bolt-action rifles minimizes the chance of damage due to a catastrophic failure.

Some have suggested these vents make the rifles unsafe. That’s not true. Japanese bolt actions are the strongest turnbolt weapons ever devised. P.O. Ackley and others used them to experiment with high-pressure loads that would have reduced other rifles to shrapnel. A great deal of flash was produced and barrels unscrewed, but the rifles tested—even late 99s—were never seriously compromised.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

In Bolt Action Rifles, Frank de Haas wrote about a Type 38 that was re-chambered to .30-06. It was a 6.5mm with a .256-inch-diameter bore, and the 0.308-inch bullet, under pressures into six digits, had to be squeezed down the bore. The cases were intact, and the rifle never developed mechanical flaws. Its recoil was outrageous, and the report cannon-like. Its owner killed a deer with it. Impressed, the National Rifle Association ran more tests on this particular Type 38.

De Haas ran similar torture tests on rather rough late-issue Type 99 rifles, which also made for fascinating reading. Back then, those rifles were about $10 apiece and seemed to be everywhere, so such experimentation was common. I encountered a hunter shooting heavy 200-grain .35 Remington rounds out of another Type 38 rifle..

The Type 38 was in ways over-engineered, but it was far and away the safest military bolt-action rifle ever produced. De Haas also noted that their general metallurgy and production quality was very high.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The Japanese 6.5x50mm cartridge was superb. Several veterans reiterated hearing the cartridge dismissed in training as “.25 Jap—not much worse than a pin prick.” Apparently, someone confused the round with the .25 ACP, the notorious Saturday Night Special pipsqueak popular with armed robbers and gamblers. Statistics maintain that the Japanese 1897 cartridge is firmly in the upper-range power category of the .30-30, regarded as a first-class deer cartridge, which is still handy in a lever-action rifle. And that is a long way from any pistol cartridge.

The Type 38 branched into two carbines: the folding-bayonet 44 for cavalry and the 38 Carbine, which accepted the standard bayonet. All of Japan’s WWII rifles were configured to accept a sheet-metal cover that reciprocated with the bolt. Many writers claim these were regularly tossed by troops, but Japanese testimony contradicts that. Most captured weapons lack those covers, suggesting they were regularly lost or misplaced after being captured. Noisy if not properly fitted, it’s possible they were dampened by the insertion of oiled strings in combat zones, but many fit securely and make no noise, even when the rifle is intentionally shaken. Also, my Japanese sources mentioned that discarding the emperor’s property was punishable by court martial.

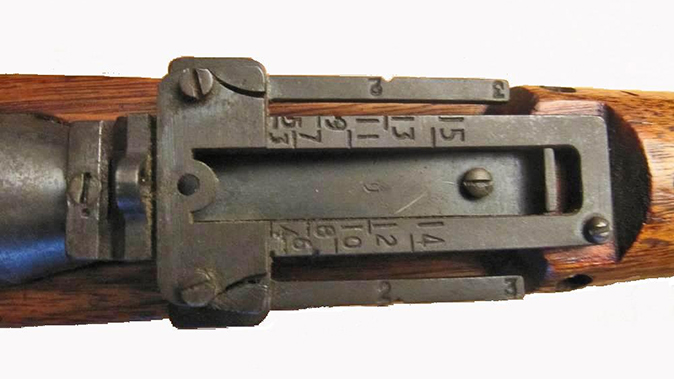

Early Type 38s—the rifle was produced continuously for 40 years—exhibit beautiful craftsmanship. Late in the 38’s career, 1937, a sniper version with a 3X telescopic sight was introduced under the new naming system as the Type 97. This scope boasted excellent optical quality but was essentially fixed with range striations so the shooter could estimate range but not move the optic.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The dust cover was retained through the later Type 99 rifles, and chrome plating of the bores and the chambers was introduced as a standard anti-corrosion measure that also sped up cleaning. More than anyone else, the Japanese knew

that primer salts caused metal to decay.

The Type 38 saw action in World War I when the Japanese quickly snapped up German possessions in the Pacific—many reclaimed later by Americans at a much higher price in blood.

Another War, Another Rifle

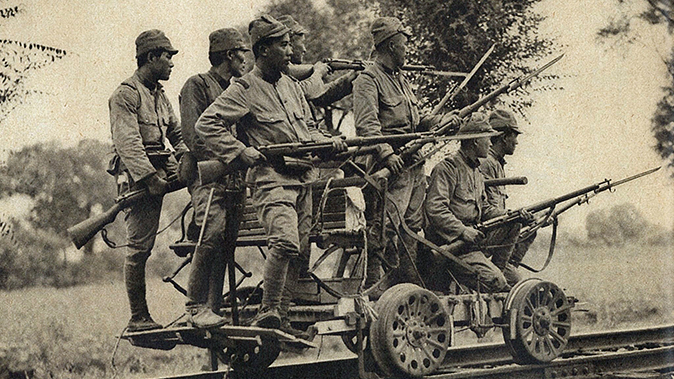

In 1931, the Japanese army invaded Manchuria, commencing World War II earlier than anywhere else. The attack upon the Chinese province seemed easy, but tactical reports suggested that new firearms were necessary. Provincial troops fielded Mausers in the potent 7.92x57mm cartridge, the German standard, and infantrymen took casualties before their rifles were in range. The overwhelming Japanese advantage in artillery and machine guns more than made up for that, however.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

A new machine gun, the Type 92, was quickly designed and in service by mid-1932, using a semi-rimmed cartridge based on the German 7.92x57mm service standard. Almost immediately, a further streamlined, slightly downloaded rimless version of the 7.7mm round began to be bandied about, and competition for a shorter, upgraded weapon built for it began.

Prototype tests at the Futsu Proving Grounds selected the Nagoya Arsenal version, or “Plan One” rifle, using straightforward modifications. This rifle, called the Type 99 (made in 1939), used a theoretically weaker action for a considerably more potent loading, meaning the safety margin was reduced. However, it far exceeded the worldwide pressure relief parameters.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The 99 action uses a larger ejector slot, slightly reducing pressure tolerances in case failures. And the overall mass of the action is reduced in critical areas. There were also a few carbines, but no official documentation exists in English or Japanese. These might have been field-modified weapons.

The Type 99 rifle included a complex anti-aircraft sight, the instructions of which constituted several pages. The fold-down “ears” of this mechanism were to tabulate lead based on estimated speed and the angle of attack, and the shooter then had to calculate range. By then, the airplane would likely have been gone. These sights were deleted swiftly.

Also included on early 99s was a wire monopod with no positive lock, mainly useless as a shooting rest, but for which inventive soldiers found other uses.

By 1941, the Japanese introduced the most practical takedown rifle of the war, giving their airborne personnel access to a full-featured, full-length rifle that, using an interrupted-thread detachment screw, could be broken into two easily reassembled halves. Superbly trained and apparently fearless, Japanese army parachutists saw considerable combat but were never actually deployed in an actual combat drop. No one knows if the navy paratroopers in the Celebes campaign even had access to the Type 00 (99 variant) takedown rifles.

No Japanese sources I contacted could explain the Type 99 long rifles. They primarily went to the navy, which had also used vz. 24s (German 8mms) and the Italian-produced Carcano Type I rifles with a Mauser-style magazine but chambered in 6.5x50mm.

The new cartridge enjoyed success in China. Ironically, against Americans in the Pacific, ranges were shorter, and the older cartridge would have served as well—maybe even better.

Sniper versions of the Type 99 are very rare, using a similar family of optics to the 6.5mm Type 97 sharpshooter’s versions. Most Type 99s respond positively to having their barrel channels free-floated and their action bedding firmed up with slow epoxy applications internally. Many early Type 38s use more stable hardwood stocks and will shoot close to 1 MOA with the best ammunition. Sierra’s 174-grain MatchKing bullet or Hornady’s similar No. 3131, topping off 4064 or Varget powder loads, have made this possible.

Exceptional Builds

Sometimes criticized for their relatively long trigger pulls and “cock-on-closing” actions, which might negatively affect the lock time and, therefore, accuracy, Japanese battle rifles are at least the shooting equal of any other five-round bolt action to see military service—and they’re far safer than most.

Ostracized by some pundits who never tested the machinery, the legends and myths of Japanese battle rifles are tied up with kamikaze, Shinto, bushido, emperor worship, ancestor-centered prayer and the fatalistic and militaristic glorifications of courage, which might explain Japanese military tactics but does not account for the excellence of the rifles.

Japanese battle rifles surrendered to Allied authorities in August 1945 show defaced imperial chrysanthemums. Those captured in battle weren’t mutilated. What tales those with unblemished markings might say, if they could, cannot be known, but they are stories of defeat in the face of a hopeless war, begun with a ridiculous excess of optimism by leaders foolish enough to dream that Americans would not fight back.

Type 38 Arisaka Specs

| Caliber: 6.5x50mmSR |

| Barrel: 31.4 inches |

| OA Length: 34.2-50.2 inches |

| Weight: 7.3-9.25 pounds (empty) |

| Stock: Wood |

| Sights: Barleycorn front, adjustable leaf rear |

| Action: Bolt |

| Finish: Blued |

| Capacity: 5+1 |

| MSRP: N/A |

Type 99 Specs

| Caliber: 7.7×58 Japanese |

| Barrel: 25.8-31.4 inches |

| OA Length: 43.9-50 inches |

| Weight: 8.6-9.1 pounds (empty) |

| Stock: Wood |

| Sights: Barleycorn front, adjustable leaf rear |

| Action: Bolt |

| Finish: Blued |

| Capacity: 5+1 |

| MSRP: N/A |