When the United States entered World War I, in April 1917, our armed forces were woefully unprepared for the conflict. Among its myriad of challenges, our military faced a serious shortage of service rifles. There were about 600,000 M1903 Springfield rifles (along with some 160,000 obsolescent U.S. .30-40 Krag rifles) in inventory at the start of the nation’s active involvement in the war. Production of the M1903 was immediately increased at both Springfield Armory and Rock Island Arsenal. However, it was soon apparent that production at these facilities would be inadequate to equip the rapidly growing number of recruits and draftees flooding into training camps across the country.

The War Department had two options for the procurement of additional rifles. The first was to contract with domestic arms makers to manufacture the M1903 rifle. However, it was soon realized that the lag time required to acquire the necessary production tooling and train a new workforce from scratch would be too great to eliminate the looming draconian shortage of rifles. The second option would be to seek another type of rifle with which to augment the standardized M1903. The government had little choice but to pursue the second option.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Fortunately, however, there was a source of available rifles. Three American firms had just completed manufacturing sizeable numbers of the “Pattern 1914” .303 caliber rifle under British contract. The machinery and trained workforces were still essentially intact and could go into production for the Pattern 1914 rifle for the U.S. government almost immediately. These firms were Remington, the Eddystone Rifle Plant (run by an affiliate of Remington) and Winchester.

While it was extremely fortuitous for the U.S. that these sources of rifles were available, the War Department was immediately faced with a quandary. Since it would take entirely too long for the three companies to tool up to make the M1903 rifle, the government initially considered adopting the British .303 caliber Pattern 1914 rifle. This would put the maximum number of rifles in the hands of our troops in the minimum amount of time. However, this course of action would result in logistical headaches by introducing an entirely new cartridge into American military service. Also, it was widely felt that the .303 was inferior to the U.S.’ .30 Springfield (.30-06).

Almost by default, it was decided to adopt a version of the British rifle modified for the American .30-06 round. However, it would take some time for the American arms engineers to finalize the engineering work required to change calibers, and the government was criticized by some for delaying the delivery of the sorely needed rifles. In retrospect, however, this was unquestionably the correct choice. In 1919, the Assistant Secretary of War Benedict Crowell stated, “The decision to modify the Enfield was one of the great decisions of the executive prosecution of the war—all honor to the men who made it.”

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The modified rifle was adopted as the “U.S. Rifle, Caliber .30, Model of 1917.” Some people today also refer to the weapon as the “Pattern 1917” or “P17” rifle. This appellation is also factually and historically incorrect as the U.S. military never used the term “Pattern” or “P” to designate weapons. The rifle is also widely, but unofficially, referred to as the “U.S. Enfield” or “American Enfield” but the only official designations are “Model of 1917,” “Model 1917,” or “M1917.”

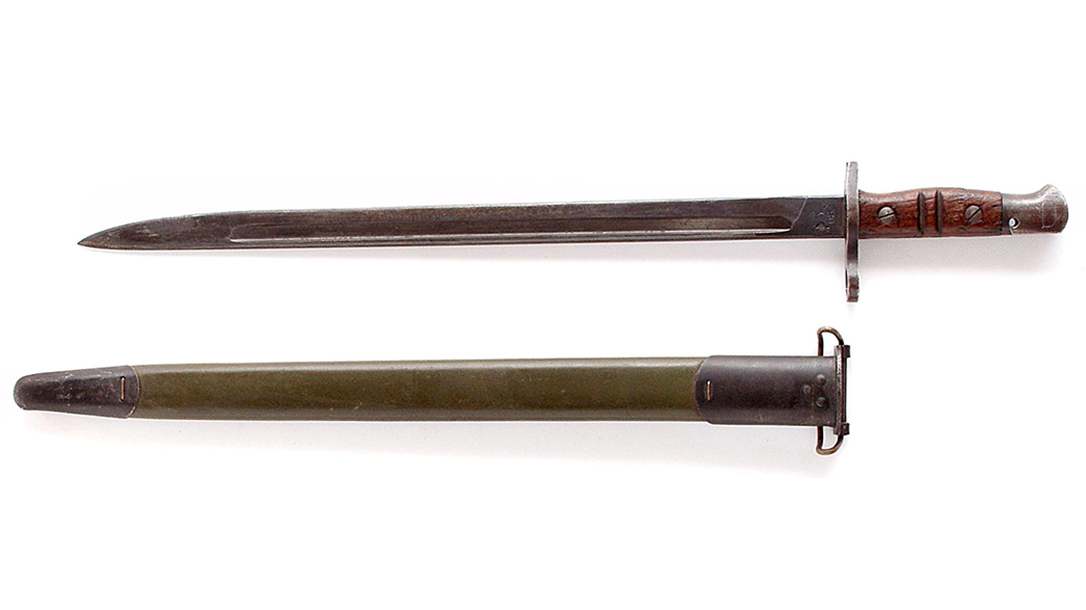

The Pattern 1914’s bayonet was also adopted by the U.S. as the “Model of 1917.” The bayonets were made by Winchester and Remington, but, for whatever reason(s), Eddystone did not manufacture M1917 bayonets. Additionally, the U.S. military acquired some of the Pattern 1914 bayonets and over-stamped the British markings with U.S. military markings.

In addition to criticism regarding the delay in production, there was a perception by some that the newly adopted rifle was not suitable for use by our armed forces. An example of this was an article in the The New York Times titled “Why our forces in France must use an inferior rifle.” The article cited a number of misleading, if not outright false, “facts” regarding the rifle. After the publication of the newspaper piece, Arms and the Man (predecessor to the National Rifle Association’s American Rifleman magazine), published an article soundly refuting The New York Times piece and also explained the valid reasons that led to the adoption of the Model 1917 rifle.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Although both the Model 1903 and the Model 1917 were bolt-action rifles, there were several differences in the mechanisms. The Model 1917’s bolt handle had a distinctive “crooked” configuration in order to place the trigger finger closer to the bolt to speed manipulation of the action. Although it may have slightly aided in manually cycling the bolt, it is a bit amusing to note that one post-war War Department report vastly overstated the utility of the design by claiming “…by bending back the bolt, we had placed two men on the firing line where there was only one before.” In addition to the configuration of the bolt handle, another difference between the M1903 and the M1917 was that the latter retained the typical British “cock on closing” action rather than the more familiar (to Americans) “cock on opening” action of the M1903.

Other complaints against the Model 1917 included the fact that it was heavier and more cumbersome than the Model 1903. Additionally, the Model 1917, unlike the M1903, did not have a magazine cutoff. This meant that when the magazine was empty, the bolt would not close unless the follower was manually depressed. This could prove awkward in close-order drills, and some soldiers resorted to inserting a dime to keep the follower depressed. While admittedly a stop-gap measure, the problem was eventually alleviated by the introduction of a sheet-metal “magazine platform depressor.” Most of these complaints were due in large measure to unfamiliarity with the Model 1917 as compared to the well-known Model 1903.

M1917 Enfield: Interchangeable Parts

Once the engineering work was finished, the three companies tooled up to manufacture the new rifle in quantity. From an engineering and technical standpoint, converting the rifle from .303 to .30-06 was not particularly difficult. On May 10, 1917, the three primary contractors submitted prototype samples of the modified rifle to Springfield Armory for evaluation. Many of the parts were also hand-fitted, which resulted in substantial lack of interchangeable components. Interchangeability of parts had been a touchstone of the Ordnance Corps since the 1830s and this situation had to be improved before the Model 1917 rifle could go into full production. Even in light of the pressing demand for more rifles, the Ordnance Corps ordered that manufacture be postponed until the interchangeability problem could be satisfactorily addressed.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

On July 12, 1917, each manufacturer sent a second specimen to Springfield. Each sample reflected varying degrees of improvement in the interchangeability of parts, but it was determined that more refinement was needed. However, in light of the ever-growing demand for rifles, the Ordnance Corps gave each company the option of proceeding with mass production and working on the interchangeability issue along the way, or delaying manufacture until the problem could be rectified. Remington and Eddystone decided to hold off on mass production, but Winchester elected to proceed at once. As events transpired, Winchester should have given the idea more thought. Assistant Secretary of War Crowell later commented, “It would have been well if the same course of action [wait for final specifications] had been followed at the Winchester plant, for word came later from Europe not to send over any rifles of Winchester manufacture during that period.”

M1917 Enfield: Acceptable Interchangeability

Although the nagging interchangeability problems were never completely eliminated, once the standardized manufacturing tolerances and engineering drawings were completed, an acceptable 95-percent interchangeability rate was reached and Model 1917 rifles began flowing from all three factories. Despite the initial problems with the Winchester-made rifles, later production guns produced by the firm were equal in quality and interchangeability to the Remington and Eddystone rifles.

M1917 Enfield: Battle Built

The M1917 rifle was 46.25 inches in length with a 26-inch barrel. The weapon also weighed about 9.18 pounds and had a magazine capacity of six rounds. In addition, it could be loaded with the standard five-round Model 1903 rifle magazine charger (“stripper clip”). The folding leaf rear sight was adjustable for elevation but not windage. In addition, the front sight blade had two protective “ears” on either side. Although not as well-suited for match shooting as the M1903 rifle’s Model 1905 sight, the M1917 sight was actually better for combat use. The stock and two-piece handguard assembly were constructed of oil-finished black walnut. In addition, the stock had grasping grooves on the forend.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The major exterior metal components of the Model 1917 rifles made by all three contractors were also blued from the beginning through the end of production. The only exceptions were very late production Eddystone Model 1917 rifles, which began to be factory Parkerized just prior to the Armistice in November 1918. However, most Model 1917 rifles seen today will have Parkerized finishes due to the extensive post-WWI arsenal overhauls to which most of the rifles were subjected. The model designation, serial number and name of the manufacturer were stamped on top of the receiver ring. The first (approximately) 5,000 Winchester-made rifles were only stamped “W,” but later examples were marked “Winchester.”

M1917 Enfield: Post-War Development

The combined output of the three civilian plants soon dwarfed production of the M1903 by Springfield Armory and Rock Island Arsenal, and the “U.S. Enfield” proved to be the predominate American service rifle of World War I. It has been estimated that at the time of the Armistice some 75 percent of the American Expeditionary Force was armed with M1917 rifles. Ordnance Corps documents reveal that 1,123,259 Model 1917s had also been shipped to France. The vast majority of these rifles were acquired by the U.S. Army, but approximately 61,000 were issued to the U.S. Marine Corps, 604 to the U.S. Navy and 70,940 were also on hand at various ordnance facilities and military installations. By the time production ceased in 1919, a staggering total of 2,422,529 Model 1917 rifles had been manufactured.

Following the conclusion of World War I, the War Department evaluated whether the M1903 or the M1917 should be designated as the standard service rifle. There were good arguments on both sides. The M1917 had proven to be an excellent combat rifle and was available in large numbers. On the other hand, the M1903 was manufactured by government owned and operated facilities (Springfield Armory and Rock Island Arsenal) so any potential future production would not be affected by labor strikes, etc.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Also, the M1903’s sights were better for target use, which was felt to be an important attribute for the post-WWI military. The “War to End All Wars” had just concluded, and it was believed that soldiers would spend more time on the rifle range than on the battlefield. Of course, that belief was shattered just a couple of decades later, but, for a variety of reasons, the M1903 was retained as the standardized service rifle and the M1917 relegated to the war reserve stockpile.

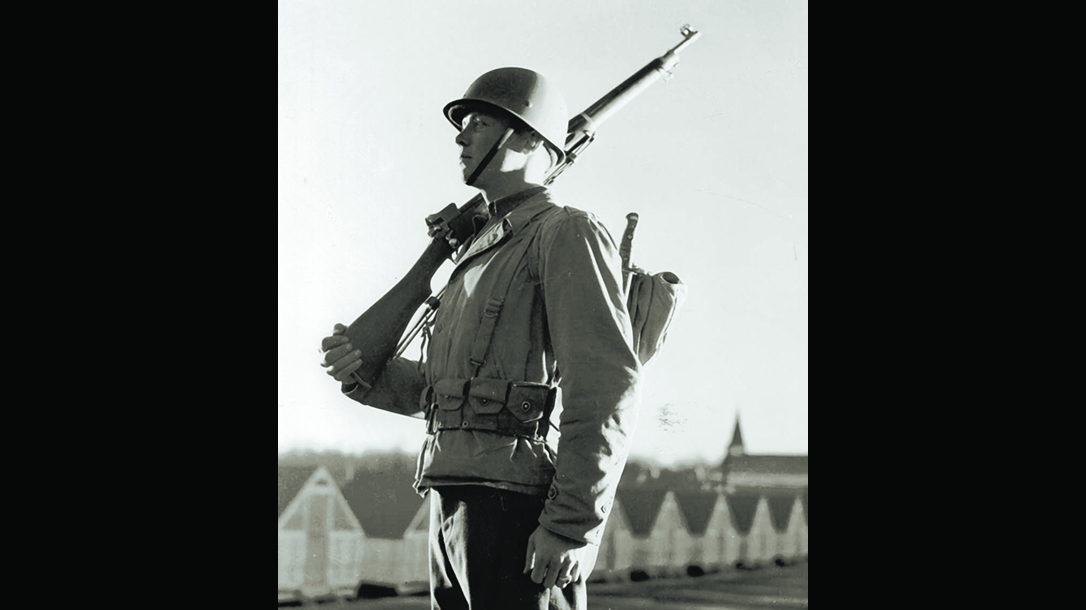

M1917 Enfield: Use During World War II

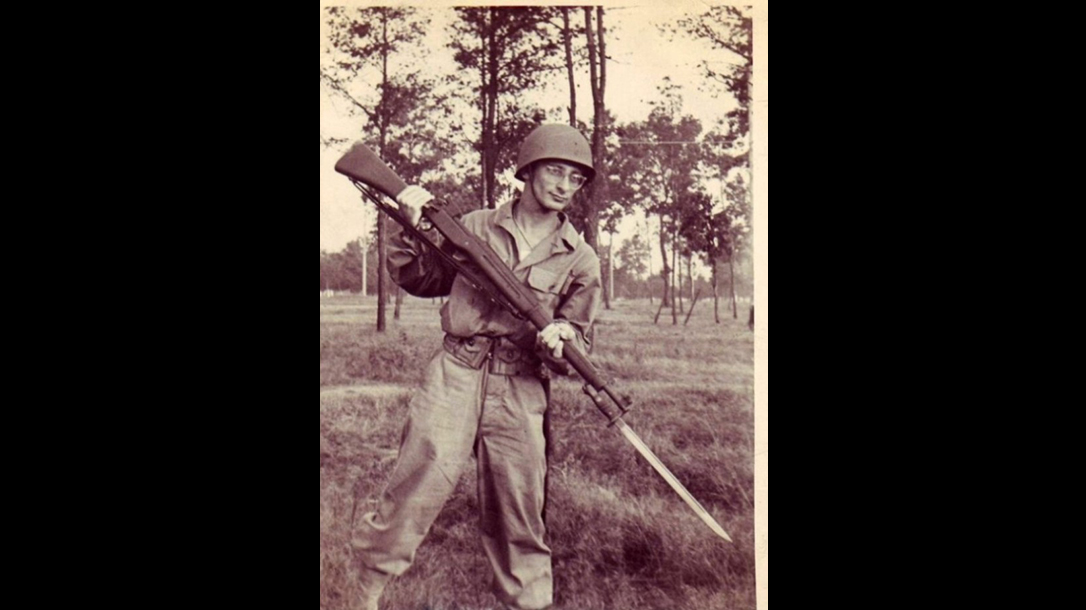

During the late 1930s, a fairly large number of M1917 Enfield rifles were sold to the government of the Philippines. During the early days of WWII, many more were provided to China. When the U.S. entered World War II, the M1 Garand was the standardized service rifle, but the demand quickly outstripped the supply and the M1917s, along with large numbers of M1903 rifles, were called back into service. Most of the M1917 rifles had also languished in storage for over two decades and many needed refurbishment. Replacement barrels were manufactured during WWII by Johnson Automatics, Inc., the High Standard Manufacturing Company and Rock Island Arsenal for rebuild purposes. In addition to replacing barrels and other parts as needed, most of the formerly blued rifles were Parkerized as part of the overhaul process.

While the M1903 saw a surprising amount of combat service during WWII as a supplement to the M1, the M1917 was used primarily for training purposes. After 1945, large numbers of M1917 rifles were sold via the Office of Director of the Civilian Marksmanship (DCM). Many were also “sporterized” to make low-cost sporting and hunting rifles. The large number of rifles given to erstwhile allies before and during WWII, the widespread arsenal overhaul programs and the subsequent civilian modifications (“sporterizing”) have resulted in unaltered Model 1917 rifles being surprisingly scarce today. Collector interest in the Model 1917 has always been much less than for the M1903. However, unaltered specimens in nice condition are finally being recognized as desirable collectibles and price tags for premium examples are continually rising.

M1917 Enfield: Call To Service

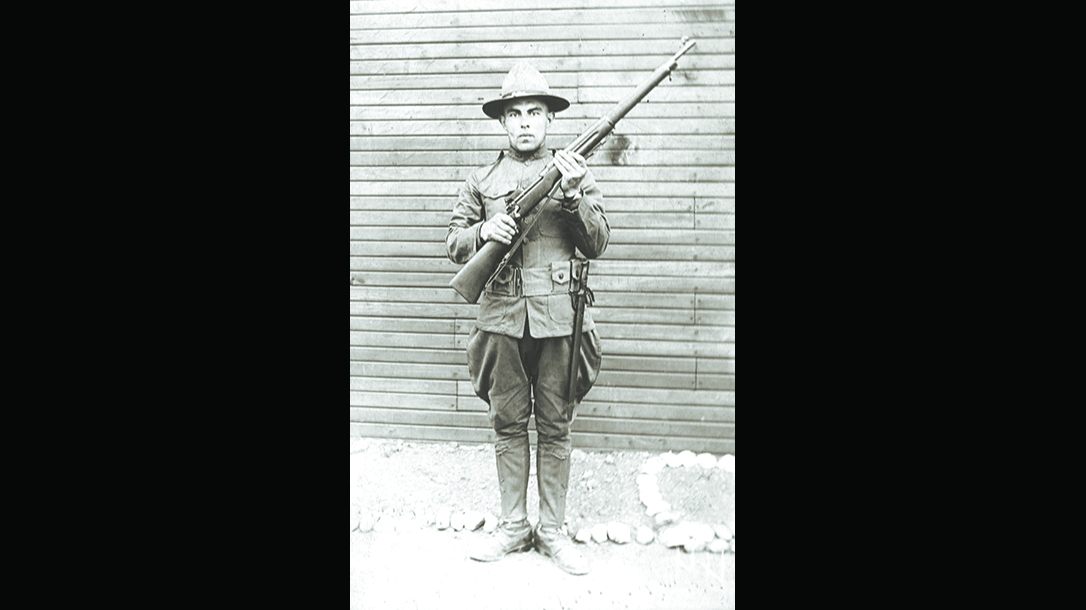

The “American Enfield” is sometimes overlooked today when considering the important U.S. military rifles of the 20th century. However, the historic significance of the M1917 Enfield rifle should not be forgotten. It may not have been the first choice of the U.S. military, but in the dark days of 1917 and 1918, the M1917 Enfield rifle provided valuable service to our “doughboys” at a time when they were sorely needed.

M1917 Enfield Specs

| Caliber: .30-06 Springfield |

| Barrel: 26 inches |

| OA Length: 46.25 inches |

| Weight: 9.18 pounds (empty) |

| Stock: Walnut |

| Sights: Rear folding leaf, fixed front |

| Action: Bolt action |

| Finish: Blued, parkerized |

| Capacity: 6+1 |

This article was originally published in “Military Surplus.” For more information, visit outdoorgroupstore.com.