The Model 1911 was never meant to be a target pistol. Not that it can’t be, it just wasn’t designed that way.

Jointly developed by John M. Browning and Colt’s Patent Firearms Manufacturing Company, the earliest semi-automatic .45 ACP pistols were introduced by Colt in 1905. The “Calibre .45 Rimless Smokeless” Model 1905 Automatic Colt, though somewhat different from the 1911, clearly established the platform that would become the most famous American-made, semi-auto handgun in history.

- RELATED STORY: Metro Arms Goes Concealable with 1911 Bobcut

Back in 1907, the U.S. Ordnance Department evaluated an improved version of the 1905 intended for the U.S. military, but the gun failed to meet the government’s expectations, sending Colt and Browning back to the drawing board to rework the design in 1909 (and again in 1910). These versions bore notable improvements, such as a change from a double-link barrel locking system to the single toggle-link design that is still used today, as well as a dramatic alteration to the grip shape and angle, which John Browning stated would improve the gun’s handling characteristics. After another government field trial in February 1910, Browning and Colt made additional modifications, at which point the gun looked essentially like the M1911 with the exception of a thumb safety. A little over a year later, on March 3, 1911, the final version of the Browning semi-auto was reevaluated by the Ordnance Department. The new .45 ACP performed flawlessly, firing 6,000 rounds of ammunition without failure and addressing all Ordnance Department concerns, including the addition of an external thumb safety so the gun could be carried with a round chambered and the hammer cocked! On March 29, 1911, U.S. Secretary of War Jacob M. Dickinson approved the selection of the Colt as the “U.S. Pistol, Automatic, Calibre .45, Model 1911.” As they say, the rest is history.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

As a military sidearm, the M1911 was exactly what the U.S. needed. But for the civilian market, it left a lot to be desired. After the M1911 was updated to the M1911Al version in 1924 (distinguished by a shorter trigger, a larger grip safety and an arched mainspring housing), Colt developed its first target model, the National Match pistol, introduced in 1933. Designed specifically for target shooting, it came equipped with a “Super-smooth, hand-honed target action—selected ‘Match’ barrel—and two-way adjustable rear sight.” Original National Match pistols were manufactured up to the beginning of WWII and reprised in 1957 as the Gold Cup National Match.

Fast-forward half a century and the Colt Model 1911 is now the most copied semi-auto in the world. The M1911 has more customized versions for defensive use, target and competitive shooting available than any other handgun in history, which leads us to the all-new, 6-inch-barreled MAC 1911 Bullseye target pistol from Metro Arms.

MAXED OUT

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

I can remember purchasing my first long-slide 1911 back in 1988 (which is easy since I still have it), and the first thing I did was have the gun fitted with a target trigger as well as extended grip and thumb safeties. I also had the barrel ramped and throated and added adjustable target sights. At the time, this was a pretty hefty investment in a 1911 that wasn’t manufactured by Colt. I ended up with a customized long-slide 1911 that has been dependable, accurate and lost none of its appeal over the last 25 years. Imagine my surprise when I received the new Metro Arms MAC 1911 Bullseye and found pretty much the same gun, right out of the box, as I had custom built a quarter of a century ago.

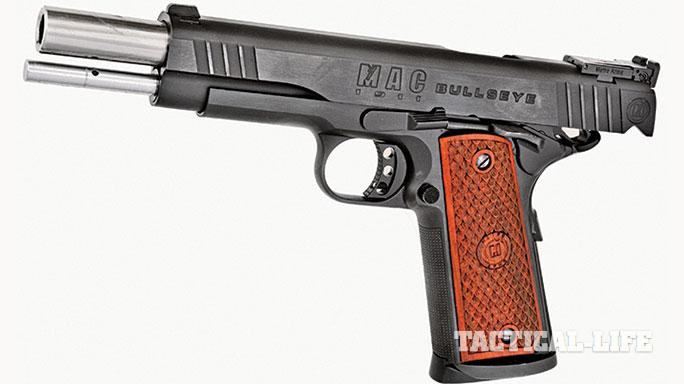

Manufactured in the Philippines by Metro Arms, the new MAC 1911 Bullseye is a refined, long-barrel version of the company’s popular MAC 1911 Classic target model, a finely tuned semi-auto with a wealth of features. While the Bullseye is shorter than a traditional Long Slide (which has a 7-inch barrel), the MAC 1911 adds an inch to the Government model’s 5-inch barrel and slide to make this an ideal target pistol.

The differences between a sidearm and a target pistol come down to specific refinements in operating features, ease of use, speed in reloading, barrel construction and, of course, accuracy. Each feature adds to the price. A Government Model that has been custom built will generally set one back anywhere from $2,300 for a Kimber Gold Combat II, to $2,800 for a Les Baer Ultimate Master Combat, and up to $5,000 for a handcrafted competition model from Wilson Combat. Under $2,000, there aren’t a lot of target pistols (outside of Springfield Armory’s Trophy Match edition), so when the fully optioned MAC 1911 Bullseye 6-inch comes in at a suggested retail price of $1,204, you have to take notice.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

For little more than the price of a basic upgraded 1911, the standard Metro Arms Bullseye gives you an extra-long, ramped, match-grade bull barrel; a 4140 hammer-forged steel slide; a fully adjustable BoMar-style rear sight; a dovetailed front sight with a bullseye center; a flared and lowered ejection port; an extended beavertail grip safety; a skeletonized target trigger and combat hammer; wide front and rear slide serrations; a finely checkered frontstrap and flat mainspring housing; an ambidextrous thumb safety; a widened magazine well; and an eight-round magazine. For the most part, that is the list of features considered requisite upgrades for a competition-level .45 ACP target pistol, so you have to ask the obvious questions. How well does Metro Arms build its 1911s? Do they have the quality of fit and finish you expect from a match-grade target pistol? And, most importantly, how do they shoot? Although the standard features of the MAC 1911 Bullseye imply high expectations that the price does not support, it all shakes out on the test range.

HITTING BULLSEYES

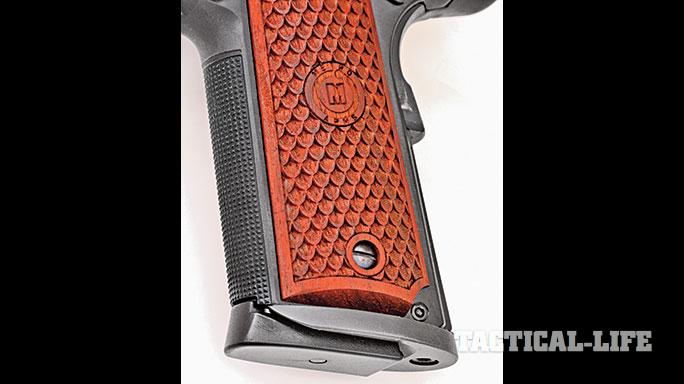

The MAC 1911 Bullseye has a combination matte/polished extended frame and slide, with the flat surfaces polished bright. The top of the slide is beveled and finished in a smooth matte blue/black, which corresponds to the underside of the frame, the inside flats of the slide serrations, the front and backstrap panels, the magazine well bevel, thumb safety, slide release and beavertail safety. The custom hardwood grips have a deep textured, fish-scale design with a full border outline and the Metro Arms logo in the center. Visually, it is a handsomely finished firearm.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The trigger pull on my test gun averaged a light 4.8 pounds. The skeletonized trigger is metal-injection-molded and has molded-in fine checkering across its face. The adjustable trigger has only 0.125 inches of travel to drop the hammer and a negligible 0.062 inches of overtravel. The slide release is light and easily activated (even when not chambering a round). The ambidextrous thumb safety clicks up and down with authority, and the hammer cocks with modest effort. The slide demands a solid, but not excessive, pull when clearing the gun or chambering the first round. It is, however, a very quick, solid pull to the rear, making it feel somewhat different from a traditional Government Model slide due to the elongated recoil spring. In addition, the extra inch of barrel and slide length increases the sight radius and makes the gun just a tad nose heavy, which is an advantage for a target pistol.

Since the Bullseye’s match-grade bull barrel is ramped for loading hardball ammunition, my test cartridges consisted of 230-grain FMJs plus three popular defensive rounds. On the high end of the defensive scale was 230-grain Federal Premium Hydra-Shok jacketed hollow points (JHPs), followed by 185-grain Hornady FTX Critical Defense and Speer Gold Dot HP rounds. The Bullseye will handle each one but can experience feeding issues with some defensive loads (Metro Arms offers a recoil spring change to correct this problem). This, however, was not an issue with the Hydra-Shoks, but there were a few hang-ups with the lighter 185-grainers.

The hardball .45 ACP passed through my chronograph’s traps at 850 fps, the heavyweight Federal Hydra-Shok slightly faster at 873 fps, while the Hornady and Speer both flew at 1,030 fps. All tests were done using a two-handed hold from a rested position at 25 yards (75 feet), shooting at IPSC targets suspended from a Law Enforcement Targets’ Range-Pro target stand.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The best five-round group with 230-grain hardball ammo measured an even 2 inches clustered around the “A” of the IPSC target. Of the defensive ammunition, Federal’s 230-grain JHPs functioned best in the MAC 1911 but had the widest group, measuring 1.95 inches. Speer’s 185-grain rounds produced the tightest group, measuring 0.85 inches, with five Hornady 185-grain FTX rounds clustering into 1.75 inches, but there were occasional feeding issues with both in the MAC 1911. For target shooting, 230-grain hardball is the best (and most affordable) choice.

Aside from the occasional failure to feed with 185-grain defensive ammo, the MAC 1911 functioned flawlessly, was quick to reload, and, with the BoMar-style adjustable rear sight and crisp trigger pull, proved more than adequate in the task of printing tight groups, firing off-hand at 25 yards with open sights.

BUILT STRONG

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

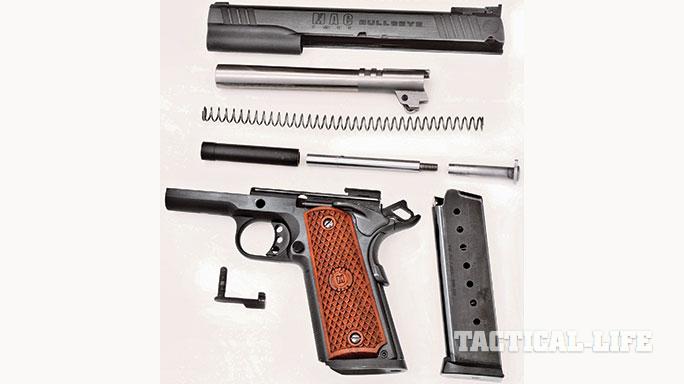

The MAC 1911 Bullseye checks out as a quality-built firearm, but not everything is perfect about the design. Having a 6-inch barrel, an elongated recoil spring and a two-piece guide rod presents some interesting challenges when field-stripping the gun, and the takedown and reassembly steps (one does not simply reverse the order) must be strictly adhered to. It is a longer field-stripping process than a traditional 1911, but, then again, this is not a traditional 1911. As a dedicated target pistol, the MAC performs well, and, with practice and hand-loaded ammunition, would easily be capable of printing groups under 1 inch at 25 yards.

- RELATED STORY: Metro Arms Releases ‘Short’ Model of SPS Vista 9mm

Overall, for an entry-level competition gun, the MAC 1911 Bullseye seems to be worth the asking price. It is also available with a deluxe hard-chromed finish and a red fiber-optic front sight.

For more information, visit metroarms.com or call 732-493-0333.