The 1920s and 1930s represented a seminal period in American history. The nation was clawing its way out of the Great Depression while advances in industrial technology brought us heady stuff like automobiles, radios, telephones and electric lights. As the United States redefined itself in light of these technological developments, some unsavory characters rode the crest of this revolution to infamy.

The popular term of the day was “motorized bandit.” The advent of the powerful V8 engine made automobiles fast enough to whisk a bank-robbing crew in and out of a town before authorities could mount an effective response. Those ne’er-do-wells brazen enough to embrace this life captured a struggling nation’s imagination and, for some, attained folk hero status. The fact that they stole money and slaughtered innocents in the process is frequently glossed over in historical tomes. In more contemporary terms, these men were closer to terrorists.

Tools Of The Time

The Thompson submachine gun and, to a lesser extent, the Browning Automatic Rifle got all of the press. However, these machine guns were expensive and relatively difficult to obtain. In addition to a broad array of handguns and semi-automatic rifles like the Winchester Model 1907, Prohibition-era gangsters frequently used state-of-the-art shotguns.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Firearms luminary John Moses Browning designed his definitive Auto-5 shotgun in 1898. The Auto-5 hit the commercial market in 1900 as the world’s first successful autoloading shotgun. Svelte, trim and elegant, the Auto-5 remained in continuous production until 1998, two years shy of a century. The Auto-5 was the second-most produced autoloading shotgun in history, just behind the Remington Model 1100. Of his 128 patented designs, Browning described theAuto-5 as his “best achievement.”

The developmental history of the Auto-5 reads like a soap opera. Browning attempted to sell his Auto-5 design to Winchester, only to have company officials balk at his terms. He subsequently offered his design to Remington. In a darkly unexpected turn of events, Remington’s president died of a heart attack in the midst of negotiations. In frustration, Browning approached Fabrique Nationale in Belgium. The subsequent rich relationship between FN and Browning produced the P35 Hi-Power pistol, the action of which drives almost every combat handgun today.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The Auto-5 is a recoil-operated design. That means the barrel and bolt assembly recoil rearward as one unit upon firing. This component cycles backward more than the length of the shell. The recoil spring then shoves the barrel forward as the empty shell is ejected. The bolt subsequently strips a fresh round from the mag before closing with the barrel to lock the shell in battery. The spring for the barrel is in the forearm. The spring for the bolt is in the stock. The overall effect is elegant.

A quirky aspect of this recoil-operated design is that various bushings must be properly configured to manage various types of loads. Each combination exerts more or less frictional force against the magazine tube during the firing cycle. Too much and the gun fails to cycle. Too little and there is excess wear and unnecessary recoil. When properly tweaked, however, the Browning Auto-5 is truly a thing of beauty to see in the field.

This recoil-driven action can be found on various familiar modern firearms. The semi-auto, .50-caliber Barrett M82 anti-materiel rifle is a recoil-operated design. A similar mechanism drove countless Model 1919 belt-fed automatic weapons during World War II and every .50-caliber “Ma Deuce” machine gun ever made. This mechanism is simple, reliable and rugged.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

I spent my youth alongside my dad in the Mississippi Delta as he and his Belgium-made Browning Auto-5 kept every Thanksgiving, Christmas and Easter properly stoked with wild turkey. It was always a bit of a competition to see who would spit out the first piece of lead shot during a holiday meal. In his capable hands, that humpbacked shotgun was pure slaughter on turkeys. And it turns out my dad was not the only one to wield Browning’s classic scattergun with deadly effect.

Guns & Gangsters

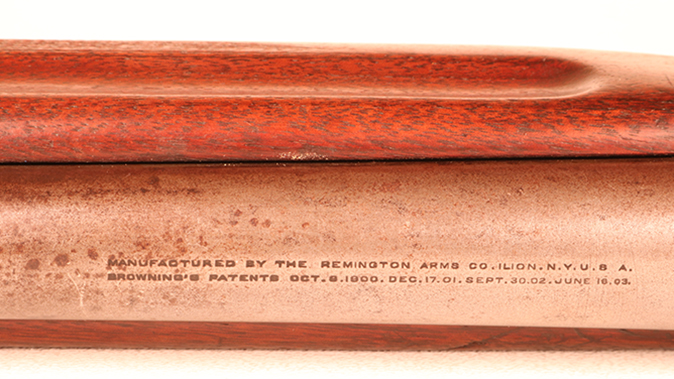

Browning eventually revisited his arrangement with Remington, and the company produced his design in the United States from 1905 to 1947. The primary difference between the Remington variation and Browning’s Belgium guns was the Remington’s lack of a manual magazine cutoff. The weapons were otherwise essentially identical. During the 1920s and 1930s, the Remington Model 11 was the most advanced shotgun in the world. Additionally, thanks to the gun’s recoil-operated action, the weapon remained reliable independent of barrel length. For folks who liked to pack their shotguns underneath trench coats, for example, this became a critical attribute.

All of the major players used them. Whenever a notorious gangster was killed, captured or forced to flee and abandon their arsenal, the Remington Model 11 always figured prominently. In addition to ne’er-do-wells like John Dillinger and Clyde Barrow, the Remington Model 11 also found utility on the right side of the law.The arsenal of weapons the FBI seized from the Dillinger gang included at least two Model 11s. One was a fairly stock variant with a riot-length barrel. The other was a “whippet” version that had the barrel and stock pruned back starkly for better concealment.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Landing Your Own

Belgian-made Browning Auto-5 shotguns command a premium today because of their superb workmanship and the allure of the gun’s European origins. By contrast, vintage Remington Model 11s are dirt cheap on the used gun market. Remington produced about 850,000 Model 11 shotguns before the end of production in 1947, and they were used fairly extensively by the military for training and operations during World War II. FN moved production back to Remington when the Nazis overran Belgium.

As a result, America is awash in old Remington Model 11 sporting shotguns. These guns carried generations of American hunters through many hunting seasons. Given the robust and reliable nature of the design, these tough old guns age remarkably well.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

High-mileage civilian sporting versions are unnaturally cheap. The gun you see here in this particular article rolled off of the Remington lines in 1913 and set me back less than $250 on GunBroker.com. I was really taken with the beautiful gray patina. These classic weapons frequently still have lots of life left in them. Because production ceased in 1947, all Remington Model 11 shotguns are eligible for unfettered shipping to a personal Curio and Relic FFL.

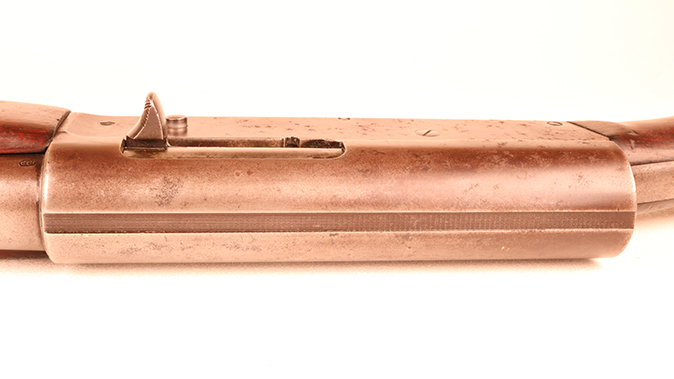

This Model 11 sported a long 28-inch hunting barrel. I pruned the tube back with a cutoff wheel on my table saw and dressed the muzzle end with a Dremel tool. I cut mine to just a hair longer than 18 inches, the legal minimum.

A little attention with my drill press and a hand tap emplaced an otherwise unadorned brass bead front sight secured with thread locker. Should you choose to follow that path, the project is well within the capabilities of anybody with rudimentary mechanical skills. Everything you might need is available on Amazon. Be sure to grind down the base of the front sight from within the bore to leave it unobstructed. With a small sanding drum, my Dremel tool accomplished that with ease.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The forearms on all high-mileage Remington Model 11 shotguns are split. Firing this recoil-operated gun without the recoil bushings in the proper configuration inevitably takes a toll. Some sport a simple crack. Others are in pieces. I discreetly drilled a toothpick-sized hole across the split and then glued a toothpick in place with wood glue. I clamped the assembly while the glue dried, then carefully sanded the toothpick ends off with the Dremel. This places the stress of the failure in shear crossways along the shaft of the toothpick. Provided you take care and touch up the sanded end with a spot of dark walnut stain, the repair is almost invisible. A toothpick is fairly fragile, but a forearm crack repaired in this manner is remarkably robust.

Trigger Time

My old restored Model 11 is reliable and effective despite its age and questionable parentage. The recoil is manageable, and the stubby barrel is handy and maneuverable even by modern standards.

Because the chopped barrel has no choke, the patterns are expansive, even at close range. However, such a gun would still perform well as a home-defense weapon, even today. When charged with 00 buckshot, the gun would also be a decent close-range brush gun for deer.

With the magazine plug removed, the shotgun carries four rounds in the magazine and one in the chamber. The Model 11 interfaces nicely with the human form, and the push-button safety is easy to manage with your trigger finger. In addition to some superlative ergonomics, the classic humpbacked receiver just looks cool.

Remington Model 11 Legacy

Dillinger and his ilk chose their guns for maximum intimidation and firepower. The semi-auto’s durability and capacity for barrel shortening made it the go-to scattergun for bank robbers and motorized bandits of the 1930s and the lawmen who chased them. The sensational nature of their crimes brought us the National Firearms Act (NFA) of 1934. This birthed the rules that govern private ownership of sound suppressors, machine guns, and short-barreled rifles and shotguns within which we still operate.

An original vintage Thompson submachine gun will cost you as much as a luxury automobile. If an original Colt Monitor BAR were offered for sale, it would set you back as much as your house. By contrast, you were ripped off if you dropped more than $300 on a pleasantly worn Remington Model 11 shotgun. Although it might not carry the allure of those expensive classic stutterguns, a period shotgun such as this still carries some hefty historical credentials without incurring any NFA registration baggage. If you are a student of the gangster period and want to add a real gangster gun to your collection, the Remington Model 11 is the economical way to go.