More than a year has passed since the second phase of the Precision Sniper Rifle (PSR) program submission deadline, and the wait for a final decision is over. Remington Defense’s Modular Sniper Rifle, or MSR, topped a group of five companies to win the U.S. Special Operation Command (USSOCOM) contract. The Remington MSR was specifically developed to meet the needs of the PSR program, which encompassed a set of requirements in a weapon system that would enable snipers to use one or more shots to interdict enemy personnel, positions and non-technical vehicles mounted with crew-served weapons out to 1,500 meters.

PSR By Definition

To get an idea of what the Remington MSR is all about, a review of the USSOCOM performance specifications for the PSR will tell the story. The PSR was specified to have an overall length no longer than 50 inches fully extended without a suppressor, with the ideal set at 40 inches. With the stock folded, the maximum length was 40 inches, with 36 inches set as the objective of USSOCOM. The threshold weight for the weapon with a Picatinny rail and a 10-round, unloaded magazine was 18 pounds, and the objective weight was no greater than 13 pounds. The base Remington MSR tips the scales at 13 pounds, and its complete configuration weighs 17 pounds.

Another aspect of a PSR is its capability to switch barrels from one caliber to another by a soldier in the field. The MSR can easily switch between .338 Lapua Magnum, .300 Winchester Magnum and 7.62mm NATO barrels. To mate up with various barrel configurations, the MSR’s bolt has a quick-change bolt head to accommodate the various chamberings. Although not submitted for the PSR trials, the MSR is also offered in .338 Norma Magnum.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

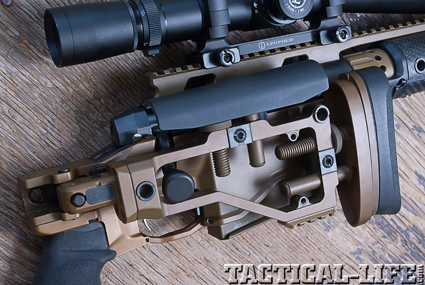

According to the PSR specs, the “rifle shall incorporate an adjustable stock for length-of-pull adjustments, and an adjustable cheekpiece that shall provide adequate adjustment to allow for eye alignment with optics. The PSR rifle shall accommodate a quick method to decrease the overall length of the stock for tactical carry/enhanced portability without separating the action from the stock…” The MSR accomplishes these thresholds with a tubular, free-floating handguard with a Mil-Std-1913 top rail, which offers plenty of space for in-line night-vision devices. Side and bottom rails allow for mounting a number of other accessories. Three configurable short Picatinny rails can be moved along the 3, 6 and 9 o’clock surfaces of the handguard.

Meet Big Green’s MSR

My first introduction to the MSR was during a Remington-sponsored writers’ event held at Gunsite Academy. My range time with the MSR was limited to about 20 shots at steel targets between 400 and 700 yards. The shots on steel at Gunsite were entertaining, but it didn’t give me a good frame of reference to compare it to other PSR-specific weapon systems I’ve tested for Tactical Weapons. For that reason, I later connected with Greg Baradat and Robby Johnson of Remington Defense at the Fernan Shooting Range in Couer d’Alene, Idaho, for a more in-depth shooting session. Prior to their Remington employment, both men were U.S. Army snipers with plenty of combat experience.

“We were the first to do the right-side folder with bolt capture for jumping,” Baradat said. “We were the first to bring the right-side folder to the game. Everybody liked it because it keeps the slick side to your body when slung.” The MSR’s buttstock is removable, too. “We wanted a foldable and a removable buttstock so we could put it in a backpack or a suitcase.” That led Remington engineers down the road to make additional changes.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

“What we submitted to the USSOCOM PSR was a lightweight buttstock,” Baradat continued. “The new design allowed us to take a pound off the buttstock. It has throw levers instead of screw dials, too. This allowed us to put set nuts in the design to retain a shooter’s stock settings,” Baradat added. “The adjustable buttplate is spring loaded, which allows the butt to be adjusted up or down just under 0.25 inches at a time.”

“Moving parts are going to wear and you’re going to get some slop in it,” Robby Johnson said. “We’ve made a screw adjustment that will tighten up the stock hinge to get the slop out of it. We made it [the stock’s moving parts] to be user adjustable. Some guys like it tight, and others like it to move freely.”

“The MSR has a titanium action that our multi-caliber barrels slip into with a barrel extension, sort of like an AR,” Baradat said. “Remington’s forged 5R barrels shoot really well, and we also use Bartlein 5R barrels. We let the customers decide which barrel they want. For USSOCOM, the barrels are FNC [ferric nitride carburization] coated—it’s also called Melonite. The action—the titanium portion—is PVD ion-bonded. The reason for having both coatings is that they provide protection from 96 hours of salt fog, per the military testing. And it increases the hardness to extend the life of the barrels. FNC ups the Rockwell hardness to nearly 70, which is really hard. We have had really good luck with barrel life, extending it by a third. The PVD on the action gives it a bit more lubricity to help feeding, letting it work better in rough environmental conditions, and it makes it easier to clean, too. It’s not a paint that will wear off.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

“The barrel nut is exposed, and has finger groves to help turning it,” Baradat said. “We like to use a torque wrench on the barrel nut for barrel changes because snipers like consistency. Without torquing it, you can’t guarantee consistency. We can attest that it will stay within a minute of angle [MOA] on and off. It will be close from one time to the next.

“The action takes a 700-footprint trigger,” Baradat stated. “For SOCOM, we worked with Tom Myers to make a solid-piece trigger housing on a two-stage trigger, with 2 pounds up front and 2 pounds at the rear. It has a really wide shoe, for gloves, so you can feel it in cold conditions. We also worked with him to make it user-adjustable with the turn of one screw. If you took the screw completely out, you couldn’t mess it up. It stays within SOCOM requirements.”

More Operator-Friendly Details

“The bolt is a tool-less assembly,” Baradat said. “The way that the bolt is married up with the action, it can run a 20- or a 27-inch barrel. We just have to change the bolt heads with the caliber. That’s a feature that we operators really like.

“For .338 LM and .300 Winchester Magnum, we use our own magazines,” Baradat said. “For .308 or small calibers, it takes an AI mag. We put a magazine block in it [the action] to make it fit the smaller .308 magazines. We can do any caliber and any barrel length shooters want—up to a 4.2-inch loaded round,” Baradat added. “We have a CIP length for our mags or we have a mag block, or spacer, that you can pull out to handle rounds that are longer.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

“On the forend, the attachment comes off from the center of the chassis,” Baradat explained. “The tube diameter we use seems bigger to most. You can put an HISS or thermal all the way around without having to stagger a light or other accessory on the forearm. Everything can go in a full circle without touching. The Picatinny rail is removable and replaceable. For SOCOM, we have flush cups on the front and the rear. Our flush cups are tested to 350 pounds of linear force. The sling is going to break at the QD swivel before it is going to pull out. To mount the accessory rails, we use time inserts. You will break the screws before the time inserts will pull out. We put cable routing guides in the forearm, too. When you are running an accessory with pressure pads, this keeps it very clean, so you can prevent the cables from being snagged. We have 20- and 30-MOA offset top rails to meet any requirement. From a cost perspective, the chassis is built from 7070 aluminum, which is not forgeable and adds to the cost. We have seen other chassis get chewed up, so we wanted to keep it as rugged as possible.”

Baradat continued explaining the MSR’s configuration, “The pistol grip is an AR-style grip. You can put any style on it you want. We use our own grip with a palm swell in it. It fills up your hand. It’s not so hard that it feels slick, and it’s not so sticky that it feels gummy. The same goes for the cheekpiece. It’s not too slick, it won’t slip when you sweat, and it’s not so rough that it will give you a rash when you shoot it. Moleskin sticks well to the cheekpiece, too. And a 0.13-inch Allen wrench is housed in the cheekpiece as well.”

“The muzzle brake on this weapon is a flat-baffle AAC Titan,” Johnson said. “That marries with an AAC Titan suppressor that weighs 19 ounces. We changed up our baffle stack to decrease the point-of-impact shift when added. One good thing about AAC working with Remington Defense is that they have all the new technology and we get to work with the government. When we make some tweaks to improve it, the improvements go back into the commercial suppressors.”

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

MSR On The Range

When we arrived at the Idaho range, weapons were assembled and targets were placed at 100 yards. Initially, we set up the MSR with its 27-inch barrel chambered for .338 Lapua Magnum. We rigged a Pact chronograph at 15 feet to record velocities. Johnson, a 33-year-old former U.S. Army sniper, Purple Heart recipient and member of the Army Marksmanship Unit, was much more familiar with the MSR and eminently qualified. To give the MSR a fair shake, I asked Johnson to fire a few groups for comparison.

Since the rifle had not been zeroed, I fired at the 100-yard steel gong while Johnson watched through his spotting scope. Watching the bullets impact in the grass below the target, I made adjustments to bring it closer to point of aim. By the third shot, I was ringing steel. Further adjustments refined the point of impact. A couple of shots were fired at 200 yards, and again, adjustments were made. I moved out to the 400-yard mark and fired. The first shot struck just above the right corner of the 6-inch target. After the last adjustment, I hammered the steel target three times in succession in what appeared to be dead center.

We let the gun cool for 10 minutes before moving back to the 100-yard targets. I selected Barnes Bullets’ 300-grain Open Tip Match (OTM) loads made for Remington Defense. The first five-shot group was the day’s best, a 0.29-inch group. Shortly thereafter, I fired a 0.49-inch group. Johnson fired the next group, which measured 0.81 inches. Perhaps the tremendous heat generated by the .338 Lapua Magnum cartridge was opening up groups. The average velocity for this load was 2,692 fps.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The second load tested was Black Hills’ 300-grain Match. I fired a five-shot group that measured 1.21 inches, and then Johnson fired a 1.15-inch group. I got back on the gun and fired two 5-shot groups with Black Hills 250-grain loads. The first group measured 1.18 inches, and the second group measured 0.99 inches. The 300-grain loads averaged 2,785 fps, while the 250-grain load averaged 2,944 fps.

The last .338 Lapua Magnum load tested was Federal’s 250-grain Gold Medal Match. The first group measured 1.14 inches, and the second group measured 0.98 inches. Johnson got back on the gun and was able to fire a 0.84-inch group. This load’s average velocity was 2,881 fps.

Next we had a chance to see the weapon’s switch-barrel capability. Johnson quickly swapped the barrel and bolt head, but paused, realizing the barrel had never been cleaned after proof-testing at the factory. He grabbed his cleaning equipment and set to work. “Dewey helped us out by creating a custom bore guide that seals either a .338 or .308 bore,” Johnson said. Once he was finished, I had about three minutes to fire a few groups with two different brands of ammo. I loaded up with Remington’s 190-grain match loads, and the first five-shot group, after a fouling shot, measured 0.33 inches. Firing as quickly as I could find the bullseye, the next group came in at 0.76 inches. The chronograph recorded a 2,978-fps average.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

With seconds remaining before the park ranger would announce, “Cease fire,” I loaded up with Hornady’s 190-grain Superformance. Two rapid-fire five-shot groups measured 1.12 inches and 1.2 inches. The average velocity was a blistering 3,143 fps.

Field Evolution

While primarily designed to sell to the U.S. military, Remington has seen commercial success with the MSR. “We sold it to the National Park Service,” Baradat said, “so they can reduce their shot signature. As we evolve the parts on this system, all the parts will be interchangeable. All of the rail sections, with the exception of the top rail, are swappable between our other weapons with the RACS System [Remington Arms Chassis System].”

Throughout the afternoon, Johnson shared his experience with the MSR during the shooting phase of the military trials. While other PSR manufacturers elected to use contract shooters to showcase their systems, Remington gave Johnson the nod. In addition to his combat sniping experience, Johnson is one of the top competitive shooters in the country. Even though the trial protocol allowed each manufacturer to throw out their largest group fired, it wasn’t necessary for the MSR. All of the 1,000-yard groups came in under 1 MOA, which was the trial limit. A weapon system that can switch barrels and shoot sub-MOA at 1,000 yards speaks for itself. With the MSR, Remington has a winner in more ways than one. For more information, visit remingtondefense.com or call 800-243-9700.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below