Remington has been on the cutting edge of firearms and ammunition technology since it began in 1816. After the Civil War, when fixed metallic cartridges were being perfected for handguns and rifles, Remington brought to the market its own brand of ammunition. Then, in 1888, Remington and the Union Metallic Cartridge (UMC) Company, established in 1867, came under the same corporate structure. In 1912, they were combined. During the Great Depression, Remington changed hands again and purchased the Peters Cartridge Company, which had been in operation since 1887. This became Remington-Peters, and many Remington cartridges still use the “R-P” headstamp. From this slice of history it’s evident that Remington has deep roots in the ammunition production business.

Last year Remington took many of its traditional lead-bullet handgun cartridges and grouped them together in a new Performance Wheelgun line. The ammunition is fashioned from top-shelf components and uses Remington’s famous Kleanbore priming, which won’t rust or corrode your gun barrel. Some of the cartridges have brass cases while others are nickel plated. The bullets are available in lead round-nose (LRN) and lead semi-wadcutter (LSWC) configurations. Finally, each load is kept to a velocity that will optimize the performance of the bullet without producing undue fouling in your gun’s barrel.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Classic Calibers

Remington is currently offering loads in .32 S&W, .32 S&W Long, .357 Magnum, .38 S&W, .38 Special, .38 Short Colt, .44 Special and .45 Colt. As you can see, some of these cartridges are somewhat obscure or obsolete. But there are plenty of classics out there that can still run this ammo. For example, the .32 S&W was introduced in 1878 for the S&W Model 1½ revolver. It was initially charged with black powder, and the new Remington ammo mimics the performance of this load, as its 88-grain LRN bullet has a factory-rated velocity of 680 fps. Another cartridge from back in the day is the .32 S&W Long, which was developed for the S&W Hand Ejector First Model revolver that debuted in 1903. The Performance Wheelgun load again takes after the original black-powder cartridge and launches a 98-grain LRN bullet at 705 fps.

In 1874, Colt came out with its New Line series of small revolvers for the civilian self-defense market. One of the cartridges developed for these diminutive wheelguns was the .38 Short Colt. Depending on the maker, it generally had a 125- to 130-grain bullet. Following on its heels was the .38 Long Colt with a 150-grain bullet that was made for the Lightning revolver, and in 1892, it became the U.S. military service cartridge. Today’s Performance Wheelgun load follows closely the original with a 125-grain LRN bullet at 730 fps.

Digging Deeper

Another old cartridge is the .38 S&W, which appeared in 1877 for hinged-frame Smith & Wesson revolvers. It was popular for the same reasons as the smaller .32 S&W, but this cartridge saw more law enforcement use and even became the handgun service cartridge for the British Empire. It has been loaded over the years with bullets weighing from 145 to 173 or even 200 grains. Remington’s new load is rated for 685 fps with a 146-grain LRN bullet.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The .38 Special came along in 1899 with the introduction of Smith & Wesson’s double-action (DA) Hand Ejector First Model .38—more widely known as the Military & Police—which was built on the medium K-Frame. The .38 Special was an improvement over the .38 Long Colt with a slightly heavier bullet at a slightly higher velocity. Remington’s .38 Special Performance Wheelgun cartridges uses a 158-grain LRN bullet that travels at a rated velocity of 755 fps.

The .38 Special armed police for the greater part of the 20th century, but during the “gangster era” of the 1920s and 1930s, cops realized the cartridge didn’t penetrate the automobile bodies of motorized bank robbers, and the call went out for something more powerful. The .357 Magnum was unveiled in 1934, and the next year a S&W revolver designed for it came along—the N-Frame “Registered Magnum” that became known as the Model 27. It fired a 158-grain LSWC bullet, and the new Performance Wheelgun cartridges use that same bullet with a factory velocity listing of 1,235 fps.

.44 Special & .45 Colt

Some folks still liked big guns that shot big bullets. S&W created its DA Hand Ejector First Model .44—popularly called the “Triple-Lock”—and chambered it for the .44 Special cartridge. The gun and caliber were perfected in 1907. The .44 Special evolved from the 19th century .44 Russian and had a longer case but similar ballistics. Hand-loaders souped-up the .44 Special, and today it’s more popular than ever. The Performance Wheelgun cartridges use 246-grain LRN bullet for an average velocity of 755 fps.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

But the oldest of the new Performance Wheelgun rounds is the .45 Colt. It came out in 1873 for the Colt Single Action Army, aka the Peacemaker. The big single-action (SA) revolver was adopted by the U.S. Army and saw service for about 20 years. The Performance Wheelgun version of this load uses a 250-grain LRN bullet, and its velocity is listed at 830 fps.

Classic Revolvers

When I heard about this new Performance Wheelgun ammo, I was rather excited because classic cartridges like these allowed me to try them out in classic wheelguns. So I tried to come up with some revolvers that were almost as old and obscure as the ammunition itself. For the .32 S&W cartridge, I selected the Hopkins & Allen Safety Police with a 3-inch barrel and a five-shot capacity. It’s the archetypical hinged-frame revolver from the early 1900s, but its “Triple-Action Safety” kept the hammer off the firing pin unless the trigger was deliberately pulled.

For the .32 S&W Long, I chose a little-known Colt swing-out-cylinder DA called the Pocket Positive. It has a 3.5-inch barrel, holds six rounds and sports a hammer-block safety. It was introduced back in 1905.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Since the .38 Short Colt will chamber in .38 Long Colt revolvers, I decided on the Colt Model 1901. This was a military version of the Model 1895 DA that became standard issue in 1892. This wheelgun has a 6-inch barrel to give the .38 Short Colt a small velocity boost.

All that’s been said about the .32 S&W applies to the .38 S&W, as many thousands of inexpensive hinged-frame revolvers were made to chamber it. It did see more law enforcement use, especially in more urban areas, and S&W produced a small I-Frame model known as the Regulation Police .38. It typically had a 4-inch barrel, a blued finish and elongated wooden grips. This is the gun I chose to test Remington’s .38 S&W cartridges.

More Revolver Options

Owing to its popularity in the law enforcement, military and civilian markets, the .38 Special is one of the most widely used cartridges in the world. Many American companies have made .38 Special revolvers over the years, but there have also been a number of foreign makers, many of which copied U.S. arms. One such example is a near copy of the S&W Model 1899 from Fabrica de Trocaola Aranzabal y Cia of Eibar, Spain, that has a 4.5-inch barrel. This is a rather well-made revolver for its type, and it was cheaper than a real S&W sixgun, so I decided to include it in this test.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

For the .357 Magnum, I used what’s known as a “Pre-27.” This model was made around 1956. It had a short 3.5-inch barrel like those popular with outfits like the FBI.

Although I don’t have a Smith & Wesson Triple-Lock in .44 Special, I was able to get ahold of a Military Model 1926, an N-Frame that looks a lot like the older original version but doesn’t have the third locking point on the ejector rod shroud. This specimen has a 5-inch barrel and was made in 1947.

Finally, I wanted a military revolver for the .45 Colt but something other than the Single Action Army. The logical choice was the Colt Model 1909. This was a stopgap handgun sold to the military to supplement the older .45 Colt revolvers they were using when the .38-caliber Model 1892 was found lacking. This big DA Colt was built on the New Service frame and has a 5.5-inch barrel; it was made back in 1911.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

First Shots

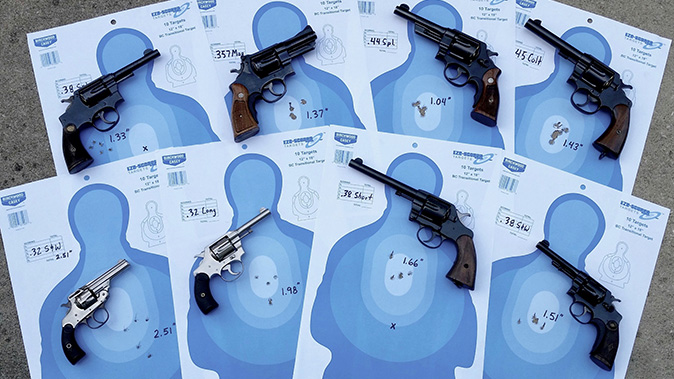

My protocol for this ammunition test was to shoot each of the Performance Wheelgun loads at 10 yards. Bear in mind that most of these classic revolvers have fixed “service” sights that vary from one model to the next. Some are fairly large and easy to see while others are rather diminutive and require a measure of squinting. Using a bench and sandbag rest, I fired three 5-shot groups in SA mode with each revolver and test load. I also chronographed each type of ammunition and fired 10-shot groups off-hand at 10 yards in DA mode.

From the get-go, none of these revolvers shot badly, especially considering the youngest in the group is 61 years old. The trigger pulls varied from horrible to smooth and crisp. For the most part, the revolvers shot to the point of aim. This might also be a testament to the quality of the Remington Performance Wheelgun ammo. Two exceptions were the Colt Model 1901, which shot high—mainly because it was sighted for 150-grain bullets instead of these 125-grainers—and the Spanish M&P knock-off, which shot about 2.5 inches to the left of point of aim.

I also had two rounds that failed to fire: one in .32 S&W and one in .38 Short Colt, but I couldn’t discern if it was the ammo or the gun that caused the problem.

More Range Results

The best five-shot group, measuring just 1.04 inches, was achieved with the S&W Military Model 1926 in .44 Special; it also had the best group average at 1.33 inches. Close behind it was the big Colt Model 1909, which scored a 1.43-inch group with the .45 Colt cartridges. In all but one case, the factory velocity specifications were lower than what was actually achieved in testing.

Again, the barrel lengths varied from 3 to 6 inches, and most of the factory ammo was shot through a chronograph using un-ported test barrels.

The rest of the revolvers kept their shots in the X, 10 and 9 rings. The sights on some of the guns were also a challenge, but for the most part, the vintage revolvers were easy to control in rapid fire and performed better than expected. The .357 Magnum in the 3.5-inch-barreled S&W bucked and roared a bit, and the big 250-grain .45 Colt load was interesting to say the least. But I wouldn’t hesitate to carry several of these guns for defensive use.

Still Making Hits

I had a very fun day shooting these “Golden Oldie” revolvers and some of the obscure older cartridges like the .32 S&W or .38 Short Colt. With Remington’s Performance Wheelgun ammunition, you can finally get your old six-shooter out and burn some powder with it.

I’d judge the loads safe with most of these old guns as long as they are in good condition. If you’re not sure, have a gunsmith check the handgun out first. Also be aware that the ammunition can be confusing. The .38 S&W and .38 Special are not interchangeable, but you can use the .38 Short Colt in a .38 Special. Some older .32 revolvers may also have issues, too. So again, if in doubt, go see a gunsmith. I do believe that this Remington ammunition lives up to its billing as being consistent, accurate and reliable.

Remington Performance Wheelgun Ammo

| Load | Velocity | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| .32 S&W 88 LRN | 533 | 2.51 |

| .32 S&W Long 98 LRN | 723 | 1.98 |

| .357 Magnum 158 LSWC | 1,152 | 1.37 |

| .38 S&W 146 LRN | 596 | 1.51 |

| .38 Short Colt 125 LRN | 631 | 1.66 |

| .38 Special 158 LRN | 708 | 1.33 |

| .44 Special 246 LRN | 717 | 1.04 |

| .45 Colt 250 LRN | 822 | 1.43 |

*Bullet weight measured in grains, velocity measured in fps by chronograph and accuracy measured in inches for best five-shot groups at 10 yards.

For more information, visit remington.com.