Since 1950, Smith & Wesson’s snub-nose J-Frame revolver series has just about defined its own genre. Of its many variations, one seems to stand above the rest in terms of performance. It is a unique blend of metallurgy and features. Let’s look a little deeper than the bare bones of how it’s described on the S&W website. My favorite of the J-Frame breed is the M&P340, which was introduced in the first decade of the 21st century. Of course, this model builds upon a decades-old tradition for lightweight, hammerless pocket revolvers, and I think the concept reached its apotheosis with the M&P340.

Beginnings

The timeline of the gun and its predecessors at Smith & Wesson runs something like this:

1887: S&W introduced its New Departure Safety Hammerless revolver, a top-break double action chambered for the short, weak, stubby .32- and .38-caliber centerfire rounds of the period. Its features are described in its “Safety Hammerless” designation. Company honcho Daniel Baird Wesson, the legend says, became concerned about children accidentally getting hold of a parent’s revolver.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

So this revolver was born. It incorporated a grip safety in the backstrap that supposedly would require an adult hand to span both that part of the “handle” and the trigger. The mechanism was designed around a very long and heavy double-action-only (DAO) trigger pull, again in the hope that a responsible adult’s hand could operate it and make it go bang but a little kid’s could not. To that end, the hammer was completely concealed inside the frame and thus could not be cocked to a lighter single-action pull. This internal hammer design led to the semantically incorrect but ever-since-enduring “hammerless” designation. Apparently, “out of sight, out of mind” was a thing even in the late 19th century.

Refinements

A hopeless attempt at “child-proofing” had been the design’s raison d’être. But what sold it to a great many buyers was the sleek silhouette of the “hammerless” design. In those days, a great many good Americans carried concealed handguns when they were out and about, and most carried them in a pants or coat pocket. An attempt to quickly draw in self-defense would often result in the spur of the exposed hammer catching on fabric and, perhaps fatally, stalling the draw. The streamlined “hammerless” shape allowed the New Departure Safety Hammerless to glide swiftly and effortlessly out of the pocket and into action. The gun remained popular well into the 20th century, but many had switched to solid-frame, swing-out-cylinder Colts and S&Ws for their small revolver needs by WWII, and after the war, S&W did not renew production of the Safety Hammerless.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Next Steps

1952: The great combat shooting authority Rex Applegate had linked up with S&W in the postwar years, and sold the company’s guns among other materiel in Latin America. While there, he carried a Safety Hammerless in .38 S&W under his shirt. The time came when he was attacked by a crazed man with an edged weapon. It took all five of the feeble .38 Short rounds in the cylinder to stop the assailant in the nick of time. Rex approached S&W and asked the company to resurrect the Safety Hammerless in the format of the conventional outside-hammer, five-shot J-Frame in .38 Special, which the company had introduced two years before.

S&W did just that and offered an Airweight version with a then-novel aluminum frame. Because 1952 was the year in which S&W celebrated its 100th birthday, the revolver was dubbed the Centennial. In the late 1950s when the company went to numerical model designations, the Airweight Centennial became the Model 42 and the all-steel version became the Model 40.

Recent Developments

1974: In little more than 20 years, times had changed. Snub-nose .38s were generally carried in holsters instead of pockets, so the snag-free hammerless design seemed less important. Those who wanted that feature could get the shrouded-hammer Bodyguard design that came out shortly after the Centennial, which left a stubby hammer tip that could be thumb-cocked. Because most users found it took work to hold a very small, light revolver steady against a relatively long and hard trigger pull, the single-action capability seemed important. Centennial sales dropped way below Bodyguard sales, and in 1974, S&W discontinued the “hammerless” guns.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

1990: Steve Melvin had become CEO of Smith & Wesson, and had wisely reached out to a broad spectrum of gun experts. He learned that the discontinued Centennial had become a sought-after cult gun among those experts, including Wiley Clapp and many more. He decided to reintroduce it, making it for the first time in stainless as the Model 640. Sales instantly exploded, and the Airweight 042 and current 442 (blued and nickeled) and 642 followed. The Centennial swiftly became a bestseller. It would be chambered for a broad range of cartridges, including the .22 LR, .22 Magnum, .32 Magnum, .327 Federal, .356 TSW, 9mm, and of course, the .38 Special and .357 Magnum.

My Own M&P340

In January of 2005, I was on the range for the SHOT Show Media Day. Shooting champion, instructor and gunsmith Ernest Langdon was working for S&W at the time, and he introduced me to the new M&P340. I fell in love with it, mainly for its sights, and ordered one. In the years since, it has been by far my most-carried backup handgun. Here’s why.

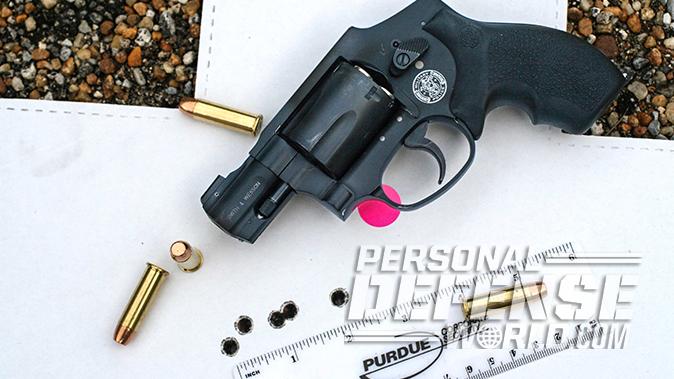

Fast-Targeting Sights: The M&P340 has a tritium XS Sights Big Dot up front, and the rear notch is deep and wide as J-Frame fixed sights go. In close, the Big Dot comes on target as fast as Express sights. The correspondingly large rear notch allows sufficiently precise alignment for on-demand headshots from off-hand at 25 yards.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Power & Recoil

.357 Mag Power: This pistol weighs just under 14 ounces, which makes firing full-power Magnum loads painful and difficult to control. However, if I wanted to load it with Magnums, I could. Remember the ammo droughts of 2008 and 2012? The .38 Special, still one of the most popular calibers, was among the first to disappear from gun shop shelves, but .357 Magnum rounds were distinctly easier to come by. That can be a critical thing under some circumstances. My favorite (and usual) carry load for the M&P340 is Speer’s 135-grain .38 Special Gold Dot +P. That load is not always readily available everywhere, and my fallback carry round for the M&P340 is Remington’s all-lead, 158-grain semi-wadcutter +P ammo.

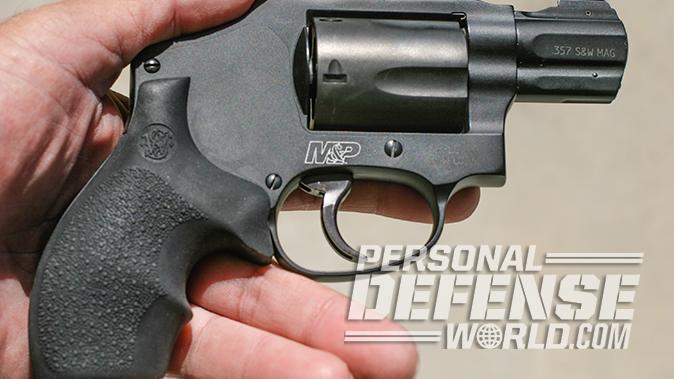

Recoil Control: Though it’s a tad lighter than the .38 Special Model 642 Centennial Airweight stainless, the M&P340 has nowhere near the kick of an 11-ounce .357 Magnum Model 340PD or the .38 Special AirLite Model 342. Yet it doesn’t sag a trouser pocket or weigh down an ankle as much as the heavier, all-steel J-Frames. Like all Centennial models, the high “horn” shape at the back of the frame allows shooters to obtain a higher grip. This reduces muzzle rise.

Tank-Tough

Durability: The M&P340 brings to the table a well-crafted mix of metallurgy. scandium alloy makes it as light or a bit lighter than a similarly sized aluminum-framed .38 Special Airweight, but it’s rugged enough to handle .357 Magnum ammo and a steady diet of .38 Special +P rounds, while the five-shot cylinder is made of PVD-finished stainless steel. The two-piece barrel is also shrouded to protect the ejector rod. Careful inspection reveals a steel shield embedded in the topstrap of the frame, just above the barrel/cylinder gap. This protects the frame from the flame-cutting effect of high-pressure Magnum ammunition.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Over the years, I’ve shot my Airweight J-Frames a lot with the hot +P ammo I carry in them. I’ve had a Model 38 Bodyguard Airweight from the 1970s rebuilt at least twice, once as a direct result of two boxes of Federal .38 Special +P+ ammo that stretched the aluminum frame’s cylinder window to the point where excessive headspace was causing misfires. As time went on, S&W incrementally strengthened its J-Frames. An early 1990s production Model 442 Airweight made it through 15 years of regular qualifications with +P ammo. Then it went in for re-timing.

By contrast, this M&P340 has now gone a full decade of frequent 50- to 100-round qualifications with +P ammo, and some full-power Magnum shooting, and has not had to be touched by an armorer yet. It’s a tough little gun.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Accessory Availability: Because the round-butt J-Frame has long been so popular, there are many grips and other accessories available for it. Over the years, my M&P340 has worn several different grips. Lately, it’s worn a set of Crimson Trace’s LG-350G Lasergrips. These offer a powerful green laser and are shaped to absorb recoil very well.

Worth The Price

As this is written, S&W’s MSRP for the M&P340 is $869. By contrast, the excellent little Model 642 Centennial Airweight in .38 Special carries an MSRP of only $469. The extremely high cost of the M&P340’s scandium accounts for a good part of that price difference, as well as the highly effective sights.

Is the difference worth it? That depends on the individual. For me, the sights were the biggest draw at first, but the revolver’s added durability has become a huge selling point. There have been enough J-Frames for a gun collector to specialize in and gather a substantial herd of them. But for my money, the Smith & Wesson M&P340 gets my vote for “best of breed.”

S&W M&P340 Specs

- Caliber: .38 Special/.357 Magnum

- Barrel: 1.88 inches

- OA Length: 6.31 inches

- Weight: 13.8 ounces (empty)

- Grip: Synthetic

- Sights: XS tritium night

- Action: DAO

- Finish: Matte black

- Capacity: 5

- MSRP: $869

This M&P340 review was originally published in “Pocket Pistols” #186. To subscribe, visit outdoorgroupstore.com.