You don’t need to carry a gun to appreciate the value of a sense of alertness. Those who do “carry” know the weight of the responsibility that rides in their holster and are happy to defuse potential encounters without having to use any force at all, let alone lethal force.

A fight deterred is the best possible victory in most respects. Predators seek prey. In the words of my old friend Clint Smith, the master self-defense instructor who runs Thunder Ranch, “If you look like food, you will be eaten.” If you think about it, one definition of “predator” would be “an expert in prey selection.”

If, by not looking like prey, you keep from being attacked at all, it’s hard to imagine a better resolution. There’ll be no blood on your hands when it’s over and none of yours on anyone else’s.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Constantly Aware

In the mid-1970s, Lt. Col. Jeff Cooper created the American Pistol Institute at Gunsite Ranch in Paulden, Arizona. It was a landmark moment for law-abiding armed citizens. Not since the sailles desarmes in Louisiana prior to the Civil War had there been a private academy that taught ordinary citizens to survive and prevail in battles to the death involving lethal weapons. Col. Cooper is no longer with us, but his legacy most certainly is.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

RELATED: Stand Your Ground Laws & Legalities: 5 Real-Life Cases

A trademark of Jeff’s teaching was his famous lecture on “the color codes.” He emphatically taught the importance of constant awareness, and inspired his students to “live in Condition Yellow,” which he described as a state of relaxed alertness.

In Yellow, said the good Colonel, you were aware of your surroundings. At any moment, if someone asked you where you were, you could tell them. If someone asked you to close your eyes and describe who was physically near you—on the sidewalk, in a restaurant, wherever—you could correctly answer them. Jeff encouraged his students to keep count of how many times they spotted a friend in public first, before the friend spotted them, and considered it a point down on your own alertness scale if the friend noticed you first instead.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Condition Yellow doesn’t mean paranoia. Far from it. Cooper famously said that a well-adjusted person should be able to spend his or her entire waking life in Condition Yellow, with no adverse psychological effects. In the decades since I learned to live by Cooper’s advice on alertness, and to teach it, I’ve discovered that it’s even better than that. Being constantly alert doesn’t have any negative effects, and it provides many benefits, even if nothing dangerous ever comes across your radar screen.

Condition Yellow makes you a “people watcher.” Where before you might have rushed through the airport from your gate to baggage claim, you now find yourself sharing the vicarious joy of seeing people enthusiastically greeted by those who love them. Where before you might have moved rapidly down the sidewalk toward your destination, you find yourself glancing at the buildings around you and marveling at the work that went into making them. When you take that daily jog through the park, you stop to watch children joyously playing, and lovers walking hand in hand. Everyone tells us to “stop and smell the roses.” I think the lesson is, when you’re in the bushes scanning for thorns, you can’t help but smell the roses.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Prepare For The Worst

More than one scholarly study has shown that the human predator will move in and attack the victim he thinks is weak—and will back off it something tells him that the “victim” in his sights is alert enough to make his attack more difficult, or strong enough to hurt or kill the predator.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

RELATED: Self-Defense & The Law: Staying Alive

The lessons? The lion culls the slow victims from the herd, not the fastest ones, and certainly not the ones the lion thinks can fight back effectively. The giraffe bent down at the waterhole, the ostrich with its head in the sand—they’re begging to be pulled out of their species’ gene pools. The intended victims who are obviously alert—ready to run the predator ragged, ready to call down the wrath and the might of the entire herd, or perhaps showing signs of being prepared to deal with the predator by itself—are all deal-breakers for the would-be attacker(s).

On November 28, 1942, 492 people died in the Cocoanut Grove fire because they didn’t head for the exit until the panic began. Ninety-two children and three nuns died in the Our Lady of the Angels School fire in Chicago because they huddled in their classrooms when the smoke became evident, instead of exiting when they could have. Countless people have died in airline disasters they could have survived if they’d known how to get to the exits by feel when the lights went out and impenetrable, asphyxiating smoke filled the cabin and they couldn’t find the escape hatches.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Let them not have died in vain. The horror of what happened in that Chicago school led generations of kids through fire drills and changed the architecture and fire response protocols in America’s halls of education.

From when I first started flying, and as a frequent flyer for decades since, I’ve made it a practice to scan the safety card before I even buckle my seatbelt. I look around to memorize where the exits are, how they work and, in case we go down in water, whether the flotation device is the seat cushion or a life vest under the seat. And I always check to make sure the flotation seat will in fact come free, or that the vest is indeed in place. I taught my children the same mantra as soon as they were old enough: “Wing exit, three seats forward, left. Lift in, throw out.”

RELATED: Live in Condition Yellow – Always Be Aware of Your Surroundings

I haven’t needed it yet, but it has been good to know where everything is, and to have a plan in place. And whenever I buckle the seatbelt, I always unbuckle and then refasten it—partly to make sure the thing will release and partly to remind my hand what to do.

This principle works in automobiles, too. I still mourn the loss of my now-departed friend Raul Cantero, a Castro-regime survivor of Cuba who reestablished himself in Miami as a fine trainer of security personnel and law-abiding armed citizens. Raul was involved in more than one shootout in his life.

One of those occurred when he was on a ride-along with a high-ranking cop friend in a suburb of Miami. Raul had gotten into the patrol car and started chatting with his friend, the cop. Then the shootout went down. The cop bailed, Glock in hand; Raul, perhaps the best shot there, drew his Smith & Wesson and fumbled for the door handle to get out to engage—and realized he couldn’t find the door handle. He was not where he could fire through the windshield. The cops took care of business before he figured out how to open the door. He shared that lesson with me and with his many students, and now in his memory I share it with you. When you get into any vehicle, after you close the door, make sure you can open it again. Memorize the door handle location and operation, and the unlocking mechanism location and operation!

Aerial Disaster

Flash-forward to January 26, 2013. My buddy John Strayer and I went aloft in a helicopter with pilot Graham Harward to hunt hogs from the air with .44 Mag revolvers in Okeechobee, Florida. Before we took off, we were given a safety briefing regarding the heavy-duty seat harnesses. A nice person strapped me in and told me how to release the strap. Then, of course, I released the strap. I wanted my hands to know what to do if the worst happened, even though we weren’t expecting it.

Less than 10 minutes into the flight, the worst happened. We were tracking a hog that had run into a copse of trees, and as we flew over the trees to catch the oinker coming out the other side, the engine failed. In a few seconds we lost altitude, and the rotors hit the treetops. In an instant, autorotation was out of the question—we no longer had rotors. It turns out helicopters don’t have much of a glide path.

The helicopter crashed nose down and upside down. As soon as movement stopped, my hand followed the plan, releasing the safety belt. I was the first out of the aircraft, crawling backward through the shattered Plexiglas. John came out next, and together we extricated the pilot. We all got out alive. Planning helped.

So did training. I had been on the starboard side of the helicopter, with the pilot in the middle and John on the port side. John had spotted the first pig, so it was his; I went into photographer mode with my own .44s still holstered while John held his at low-ready, with his trigger finger indexed on the frame of his S&W Model 29 revolver. When we went down, it was too fast to allow for reholstering. John rode the aircraft into the ground with brutal impact—his hand and gun were driven through the Plexiglas nose of the aircraft—and his finger never got near the trigger. He still has the scars on his hand from where the ragged edges of the Plexiglas filleted his finger down to the bone. That, my friends, is a lesson in trigger finger discipline.

As if that weren’t enough for one brutal morning, there was one more lesson reinforced in that incident. In days of old, it was common for crime prevention instructors to tell you to keep the strap of your purse or your camera around your neck so the “snatcher” couldn’t easily pull it away from you. That turned out to be a penny-wise and pound-foolish tactic. The guy who jerked your purse or camera off your shoulder left you without a purse or camera, but the same mugger who did so when it was around your neck still got your camera or purse, but now left you with a severe neck injury.

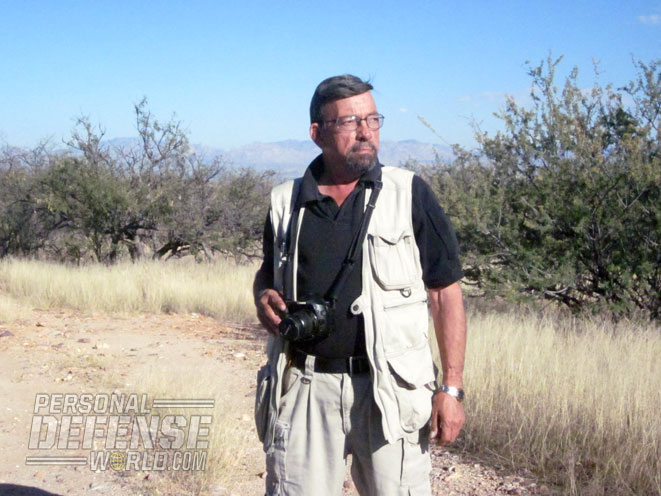

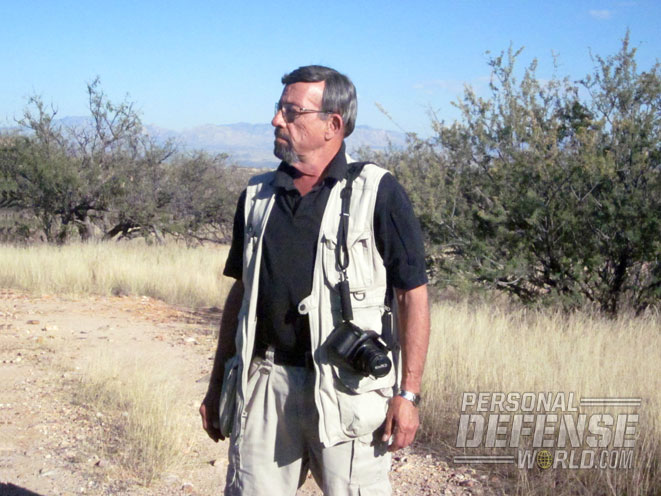

Before we went aloft in the helicopter, I knew even the most expensive camera was relatively cheap compared to a broken neck. I slung the strap over my left shoulder, the camera resting on my left thigh, when we went up. To keep from dropping it out of the helicopter, I ran the strap through the left shoulder epaulet of my EOTAC field jacket. The camera had been in my hand when I saw we were going to crash. There was time to flip it to my left, between the seats, before I brought my hands up into “crash position” to protect my eyes. One of the first things I realized when I crawled out was that the Canon SLR was still harmlessly attached to me. It was undamaged, more than I can say for my ruined eyeglasses and blood-stained clothing, but more to the point, it hadn’t bounced around inside the cabin during the violent impact and fractured anybody’s skull. And, the strap wasn’t where it could break my neck in the savage impact of the crash.

Keep Your Head Up

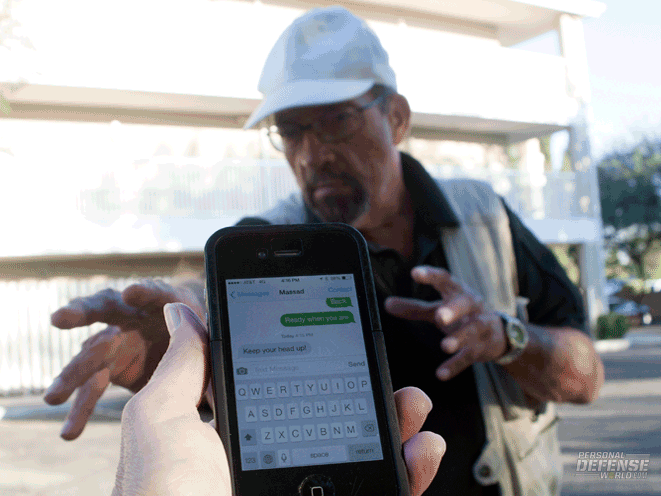

Hearing is a critical part of our danger-sensing input. It’s amazing how many people walk around wearing earbuds or the headphones that the buds replaced. These are not only literally earplugs that block ambient sound—they fill your head with sounds that further occlude perception of nearby danger signals. It’s the auditory equivalent of wearing blinders. As we focus our attention on the song or audio book we’re listening to, it’s human nature to pay less attention to the other senses.

RELATED: Be Aware: Situational Awareness Tactics To Spot Threats

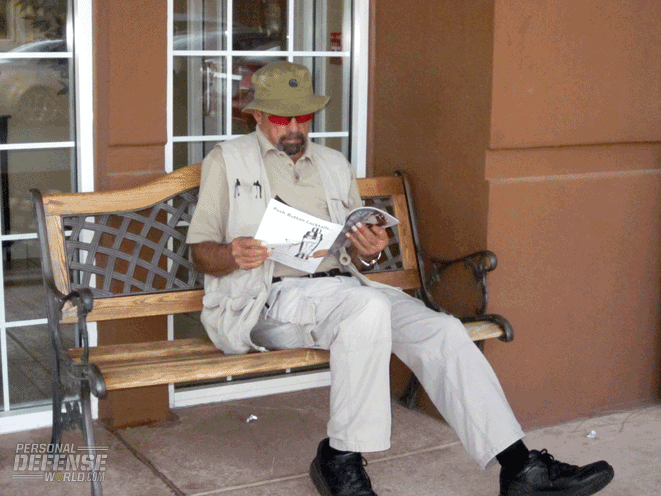

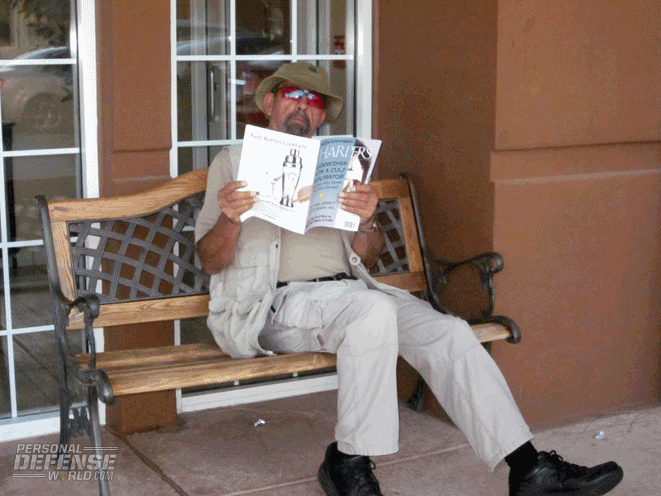

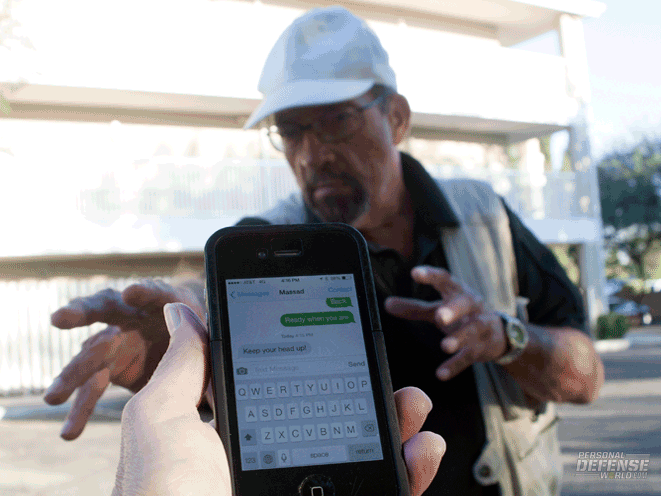

In the same way, we tend to read our newspapers, books, magazines and i-devices by lowering our head to them. Keep your head up, and bring the reading matter to your eyes! Having your head down equates to being an ostrich with your head in sand. Keeping your head up is similar to the alert gemsbok with its spear-like horns, making the lion realize he can die impaled on them.

To continue the metaphor, some predators see elevators as waterholes: a place where the prey can be easily trapped and cornered. Keep your head up. If at all possible, get into a corner; it covers your back. Keep your hands in the front of your body, where you can fend off a rapid assault. Stay alert. Stay aware. Stay safe.

This article was originally published in COMPLETE BOOK OF HANDGUNS 2014. Subscription is available in print and digital editions below.