Way back in a previous century, when I started a career as a cop, my off-duty gun was a blued, .357 Magnum Smith & Wesson Model 19 snubbie. The K-Frame was a near ideal size for such use, falling between the too-big-to-carry N-Frame in bulk and weight, and the too-small-to-shoot-well (for me) five-shot .38 Special J-Frame. In the days before the autopistol expansion, in areas where it was allowed, the .357 Magnum was a well-respected powerhouse in uniform, and the Model 19 was highly regarded.

Conventional policy was to practice and qualify with .38 Special ammo while carrying the full-bore magnum rounds of the day on duty. This worked just fine for many years after Bill Jordan collaborated with S&W to develop the K-Frame magnum in 1955. In the late 1970s, though, a new philosophy emerged, and the idea of shooting the same magnum loads for training and qualification at the range as we carried in the cruisers began to spread across the country.

This was good, encouraging officers to train more realistically, but it was also not good, bringing out a flaw Jordan had mentioned all along. The .357 K-Frame, despite its advanced construction over the older .38 K-Frames, was not built for a steady diet of magnum shooting. Frames stretched on occasion with high-mileage guns, end shake developed here and there, and, most notably, the forcing cones on K-Frame magnums were cracking at the bottom, in the flat section required by the yoke design, where the cone wall was thinnest.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

None of this shades the K-Frame magnums—it’s just a matter of physics and intended use at the time the gun was introduced. Firing .38s, the tried-and-true K-Frame was a stellar performer that typically ran fine for generations. This was fully in tune with the way most owners thought and shot in the 1950s and 1960s. Using magnums occasionally was fine in an era where very few people shot the hot stuff every weekend, and even with the common conventional magnum 158-grainers the K-Frame could hold up reasonably well with semi-regular use.

But magnum pressures were still hard on the design parameters, and the cracked forcing cone issue was further aggravated by the increasing popularity of the higher-stepping 125-grain JHPs that showed such a high degree of effectiveness in one-shot stops from law enforcement holsters. The 125-grainers were very efficient on the street but very hard on forcing cones at the range. It took a while for the correlation between forcing cone wear and bullet weight to be made, and the introduction of the larger L-Frame magnum in 1981 came about to address the issues inherent to the K-Frame magnums.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The L-Frame was so successful in creating a more durable .357 Magnum platform that it’s been in continuous production ever since, whereas S&W dropped the K-Frame magnums in 1999 (the blue Model 19) and 2005 (the stainless Model 66). The Model 19 is still only a used-gun proposition, but the Model 66 was reintroduced with a 4.25-inch barrel in 2014, and now in a 2.75-inch barrel in 2017.

When I left my first police department, I sold my snub-nose Model 19 during a moment of massive cranial discombobulation, and I’ve regretted it ever since. I acquired it used in 1976 and have no idea when it was built, but it was in excellent shape and a fine example of S&W at its best. I did stumble across a mint Model 66 snubbie years later and snatched it up as a more corrosion-resistant substitute if I ever decided to return to a .357 Magnum for concealed carry. The late-1980s production S&W has sat unfired since then.

All of that said, when Smith & Wesson was getting closer to shipping the new version earlier this year, I thought a head-to-head might be interesting. The company duly sent a test sample and we were off and running. The idea was to compare and note the physical differences between both guns, old and new, shoot several representative loads through each and tally up the results.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Old Meets New

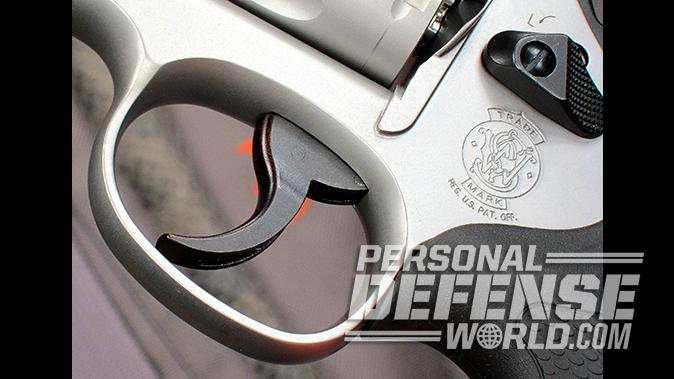

My older Model 66 looked new when I acquired it and came with a set of discontinued black rubber Butler Creek grips installed. Familiar to old S&W fans, it came with a 2.5-inch barrel, a front ramp sight with a red insert, a white-outlined micrometer rear sight, a casehardened trigger and hammer, a six-shot cylinder, and traditional front lockup achieved by the long-standing spring-loaded plunger in the ejector rod housing engaging the end of the extractor rod.

This Model 66-4 generation has an un-pinned barrel, an un-pinned extractor star, a topstrap drilled for attaching optics, a rounded rear sight base front appropriate to its time of manufacture, and yes—it also has the flat forcing cone section at the bottom. The trigger is smooth-faced, the hammer spur is the middle-of-the-road semi-target width, the firing pin is located in the hammer, and the exterior metal surfaces have the brushed finish used on Smith & Wesson stainless revolvers for decades.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

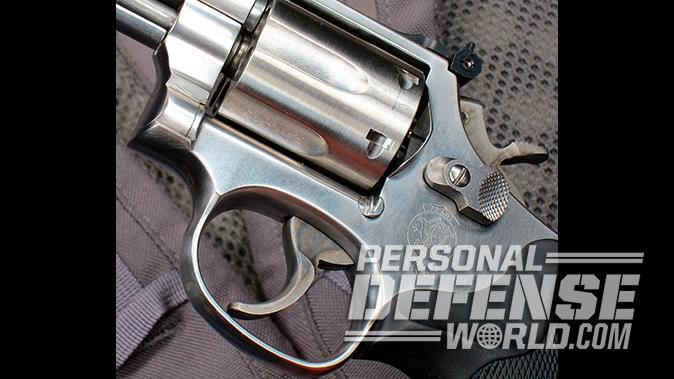

The new Model 66 shows obvious kinship. But differences crop up aside from the slightly longer barrel. The new barrel is a two-piece design—an assembly of a straight inner rifled tube and an outer shroud with a pinned red-insert ramp front sight. The grips are made of a black, lightly textured, synthetic material very close to the other revolver’s Butler Creek dimensions but made by S&W.

The fully adjustable rear sight is S&W all the way, with a rounded front tang over the drilled and tapped topstrap, but no white outline on its blade. The trigger and hammer are both MIM parts, and they share a dark black oxide finish with the thumbpiece and the visible screws. Besides the barrel length and construction, there is another significant change in front-end lockup on the new 66. The ejector rod shroud’s plunger is missing, and the longer barrel allows a longer ejector rod for better case extraction. Lockup functions have been moved from the ejector rod to a relocated plunger in the frame just ahead of the cylinder, and that plunger now engages a recess in the crane.

The gas ring in front of the cylinder has also been modified, which adds to a much tighter cylinder lockup than any S&W revolver that’s ever passed through my hands. There is enough room to eliminate the flat lower cone section of the older design, leaving full-thickness cone walls all the way round. The firing pin is situated in the frame, the hammer also uses the same semi-target width, and, interestingly, the new cylinder is fractionally longer than the older one.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The topstrap is also slightly longer, with the rear sight blade riding about 0.06 inches farther back in the frame than on the earlier 66. This is a function of a decreased arc under the hammer common to the newer-lock-equipped frames. The more subdued gray finish is a bead-blasted deal, not a chemical treatment, and of course the gun has S&W’s internal key lock.

Range Shootout

Basically, the test setup was very simple; I decided to shoot five commercial jacketed loads off the bench through both guns at 25 yards in a condition- controlled indoor range with good lighting. Accuracy was the goal, so I didn’t incorporate any speed contests or combat drills. An old MTM pistol rest was used to support each revolver.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Short-barreled .357 Magnums can produce a lot of noise and flash, and these guns were no exception. Notable muzzle flash occurred with most of the test loads, and the enclosed indoor shooting station walls bounced the concussion back into my headset and plugged ears on every shot.

The recoil of the .357 Magnum has never been an issue for me with good grips. The grips on these two guns were very comfortable with all of the test loads, even the stiffer 140-grain CorBon rounds. I’d call it a wash between the two grips; both are well contoured and slip resistant without being abrasive.

In a static, slow-fire paper shoot, the lack of a white outline on the new 66 wasn’t an issue, but I’d miss it in real-life use. Between the all-black rear sight and the not-quite-as-bright-orange front insert, the new sight picture doesn’t leap to the eye as quickly as the older one does. I’d like to see S&W correct this, especially in a gun more likely to see use for concealed carry than Saturday afternoon paper punching.

The 5-pound SA pull on the new 66 was heavier than it needs to be, but it’s tolerable. It broke clean when it did let go, and the 5-pound pull on the older snub also offered a clean break, so no advantage either way in SA triggers. The DA pulls were off my scale on both revolvers, but noticeably heavier in the new gun as measured by my meticulously calibrated trigger finger. Firing in DA mode, the nod clearly goes to the old model.

Any snubbie with a 2- or 2.5-inch barrel by any maker will usually suffer from a shorter ejector rod as compared to a full-length version in the same frame size. It’s a built-in drawback we trade for better concealability in short wheelguns that we just have to work around. An extra quarter-inch on the new snubbie’s barrel doesn’t sound like all that big of a deal, but when combined with the front locking plunger being moved out of the way, the two modifications allow a full-length ejector rod without detracting from the overall concealability of this model in any practical way. It’s definitely a plus on the side of the new model here.

The Forcing Cone

Internet reports have detailed cases of jacket shaving and blowback with new snub-nose 66s. I started testing with the older 66 and encountered a single instance where one CorBon 140-grain JHP shaved so badly that it deposited chunks of jacket material between the top of the forcing cone and the topstrap large enough to stick out and bind up the cylinder’s rotation. I had to carefully chisel them out with a small screwdriver and hammer. That never happened again with that gun, but I did get blowback from a Hornady 140-grain FTX round that stung my cheek and drew blood from my trigger finger.

With the new S&W, the same CorBon 140-grain JHP caused four cylinder jams, again depositing jacket material between the forcing cone and topstrap that bound up rotation and had to be pried out. One CorBon round also stung my other cheek with particulate blowback. What’s up?

In discussing the results of his ammunition with Peter Pi at CorBon, he said he’s noted shaving in several .357 Magnum revolvers over the years with 140-grain JHPs, and it appears to be a known issue in some guns. He uses quality Sierra bullets in his 140-grain loads.

When I laid out the results of the testing for my longtime gunsmith, he confirmed the 140-grain jacketed bullet issue (again in some guns) going as far back as his own metallic silhouette days in the 1970s. I apparently had not fired enough 140-grainers over the years to encounter it myself, but I’ll take their word for it. (Knowing how these things sometimes get themselves misconstrued, note that I am not condemning all 140-grain jacketed bullets in all guns, just suggesting that you try a couple boxes of them for functioning before adopting one as a carry load in your particular revolver.) It appears to be a combined effect of bullet ogive, bullet velocity and forcing cone angle, so I can’t entirely blame the new gun.

But in closely examining both S&Ws, a range rod shows both have perfect alignment with the bore in all chambers, eliminating timing questions as a possible cause of the shaving as far as the guns themselves go. A K-Frame go/no-go gauge passed the older 66 with an ideal cone, but showed the new cone as a definite “no go.” On this sample it’s way too shallow, which likely contributed to the more aggressive shaving. Under a jeweler’s magnifying visor and with bright light, the cone was also visibly cut off center, with a deeper angle on one side and a markedly shallower angle across from it. The rear end was also not faced squarely, and all of this combined undoubtedly created the unusual shaving and spitting issues on this sample.

S&W apologized for the manufacturing error and offered another test gun, but time didn’t allow for a re-shoot on this one. The company did say that the new 66’s cone should not be this shallow. Production going forward should gauge to normal specs, and with a wider angle and a properly centered internal cut, I’d expect to see shaving greatly reduced across the board, if not eliminated entirely from most jacketed loads.

In Perspective

The longer barrel on the new Model 66 shorty allows better ejection, the relocated front plunger facilitates a tighter cylinder lockup, the grips are a very good design, and the SA trigger is quite passable, though the DA pull is overly heavy. The non-reflective bead-blasted finish won’t glare up your position like the older semi-shiny one could. And the gun should hold up much better to prolonged magnum ammunition use with the new forcing cone.

The new model also outshot the old one in 25-yard accuracy testing even with that bad forcing cone. And just to show the 140-grainers aren’t totally out of the running, despite the cheek-stinging blowback with that one Hornady shot, the FTX rounds pulled off excellent “combat accuracy” in both snubs.

I’d still like to see the company do better on the 66’s sights, but with an in-spec barrel and the right load, this one can do a credible job as a corrosion-resistant concealed-carry proposition around town, a trim trail gun in the high country, a light backpack blaster and a compact glovebox gun. The K-Frame magnum has always been a powerful and near-ideal carry revolver in compact snubbie form, and the tradition continues with this reintroduction.

For more information, visit smith-wesson.com.

S&W Model 66 Combat Magnum Specs

| Caliber: .357 Magnum/.38 Special |

| Barrel: 2.75 inches |

| OA Length: 7.8 inches |

| Weight: 33.5 ounces (empty) |

| Grip: Synthetic |

| Sights: Ramp front, adjustable rear |

| Action: DA/SA |

| Finish: Stainless |

| Capacity: 6 |

| MSRP: $849 |

S&W Model 66 Combat Magnum Performance

| Load | Accuracy (Vintage Model) | Accuracy (New Model) |

|---|---|---|

| Black Hills 125 JHP | 2.31 | 1.62 |

| CorBon 140 JHP | 3.00 | 3.25 |

| Hornady 140 FTX | 1.62 | 1.88 |

| Winchester 110 JHP | 3.18 | 2.43 |

| Winchester 125 PDX1 | 2.62 | 1.56 |

*Bullet weight measured in grains. Accuracy measured in inches for best five-shot groups at 25 yards.