One of the most remembered attacks of the Vietnam War is the Tet Offensive. Many readers will be familiar with this event, but in general, many people do not know what it actually entailed. Not long ago, I was made aware of an amazing piece of history, an AK from the Tet Offensive that had been preserved. I will share its amazing story with you.

Background

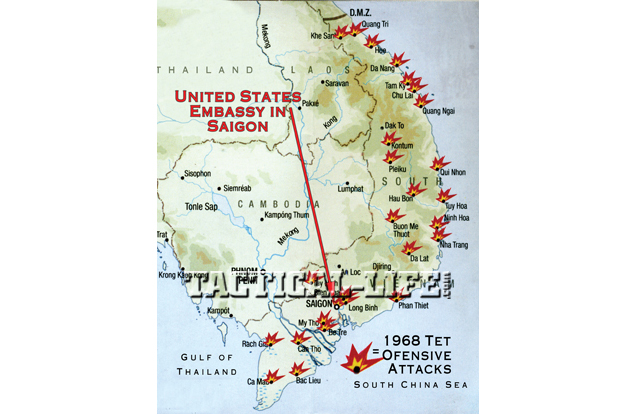

The Vietnamese word “tet” is the abbreviation for the phrase tet nguyen dan, which may be loosely interpreted as “the first day of the new period.” This is the Vietnamese New Year, a three-day celebration that is possibly the country’s most important holiday. It signifies a new beginning, leaving the old year and any of its bad luck behind. It is usually celebrated with feasting, fireworks and festivities. Even domestic work is discouraged during this time to relax and refresh. Due to the failing health of Ho Chi Minh and the belief that the Americans were making great advances and causing heavy, unsustainable losses to the North Vietnamese Regular Army (NVA), the NVA planned and carried out a surprise attack on January 31st, 1968, the first day of the lunar new year. The date was significant: The first day of Tet was typically observed as a cease-fire, so an offensive attack would catch many people off guard. During the Tet Offensive, nearly 100,000 NVA soldiers attacked several strategic targets in numerous regions. I will focus on one specific battle, the attack of the U.S. Embassy in Saigon.

Although many analysts believe the military operation itself turned out to be a failure, it is still debated and deeply believed that the Tet Offensive’s psychological effect and impact represented a significant turning point in the Vietnam War. Prior to the operation, it was beginning to look as if the war was winding down and that the U.S. would eventually cruise to victory. The Tet Offensive showed the U.S. that the North Vietnamese had a will to fight and that an increased military presence would be needed to win. This started creating doubt and concern. Even supporters of the war were quickly becoming afraid that it would then continue much longer.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

U.S. Embassy Attack

In the very early morning hours of January 31, 1968, a suicide squad numbering just under 20 Viet Cong sappers attacked the U.S. Embassy in Saigon. Entering through a hole created by an RPG-7 at approximately 2:55 a.m., they held the courtyard for almost six hours before being killed or captured. Early in the battle one VC operator was dispatched and his weapon, a Russian AK-47 (serial number EB6467 “N”), was taken from his lifeless body by Leo E. Crampsey. (Leo E. Crampsey served as the supervisory regional security officer at the U.S. Embassy in Saigon from June 1967 to March 1969 and was instrumental in defending the embassy that morning.) Crampsey states in a personal letter to Paul S. Rundle, a U.S. Secret Service special agent, that contrary to the media reports, the VC never actually made it into the embassy building. They had all been dealt with by 9:00 a.m.

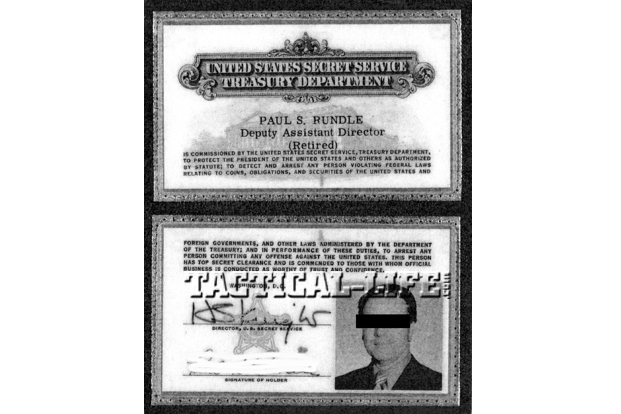

Enter Rundle

Paul S. Rundle served from 1965 until 1978, when he retired as the deputy assistant director of protective forces. During this time his duty was to protect several U.S. presidents and vice presidents (including their families) and many presidential/vice presidential candidates. During the 1968 presidential elections, Rundle’s assignments included acting as agent in charge of the Republican Convention in Miami, Florida, and as agent in charge of protection detail for Retired General Curtis LeMay, who was the current vice presidential candidate and a highly decorated World War II hero with legendary military experience. Rundle accompanied General LeMay to Vietnam (the only candidate from any party to visit Vietnam and talk face-to-face with the troops). In October 1968 on a preliminary visit occurring several days before LeMay arrived, Rundle was met by his good friend Leo E. Crampsey. During these days and to address travel plans and security concerns, Rundle visited Saigon, Nha Trang, Bien Hoa, Long Binh, Cam Rhon Bay the Mekong Delta and Da Nang. Rundle then met with LeMay, accompanying him throughout his visit. Rundle’s love for firearms did not go unnoticed by Crampsey during this trip, so prior to Rundle’s departure from Saigon, Crampsey presented him with the AK-47 he had captured during the embassy attack. Rundle returned to the U.S. with his prized AK on General LeMay’s private airplane, and when he got home, he cleaned and test-fired the gun. It has lain silent ever since. It was amnesty registered with the Director of Alcohol and Tobacco Tax Division on a Form 4467.

Over 40 Years Later

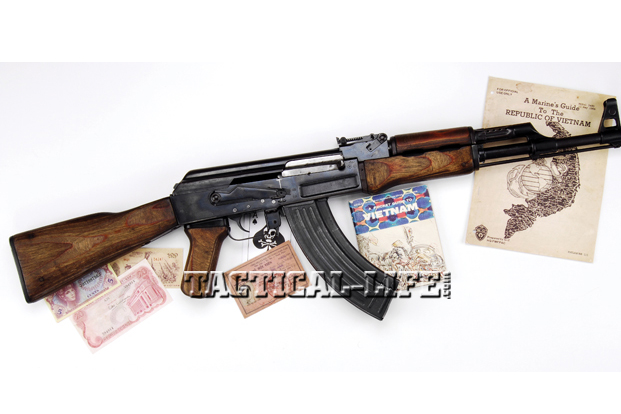

There is something else you should know about Rundle’s AK: The gun along with a collection of private letters, forms and photographs to authenticate its story, was sold to a private collector at the Fall 2009 Firearms Auction at James D. Julia Auctions in Fairfield, Maine. As soon as I learned of this, I asked if I could share this amazing piece of history with readers and photograph the gun and the supporting documentation. After getting the thumbs up, it was time for me to get to work—this was one rifle I couldn’t wait to get into. Strictly as an “amnesty-registered Soviet AK-47,” the gun was amazing—the opportunity to fieldstrip and photograph this specimen was an honor—but having so much supporting documentation and original photography to match made it all the better. The rifle, manufactured at the Izhmash plant, is an early version Russian model with a milled steel receiver. The barrel is 16.25 inches, and the furniture is wooden, including the stock, forend and pistol grip. The gun appears completely original as issued and does not show signs of any factory reworking. All its serial numbers match, including those on the receiver, the top cover and the wooden stock.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Considering that the weapon was captured during war and that its life during storage is a mystery, the weapon is in remarkably good condition, including its bright, shiny bore. Even by today’s stringent collector’s guidelines, the rifle’s original finish appeared to be at “85%+” with just a small amount of gray patina along the lower-left edge of the receiver. There was a small, eighth-inch gouge on a portion of the receiver ejection port and the adjoining bolt carrier. This may have been caused by an attempt to “deactivate” the firearm (if so, it failed miserably because the AK cycles very smoothly when operated by hand), or it could just be a battle scar obtained from its use as a military firearm. All the gun’s markings, such as the Russian Cyrillic letters and proof marks, are clean and crisp, making the pedigree easy to obtain for such a scarce rifle that is seldom found in the U.S. As a long-time collector, enthusiast and student of military firearms, I feel the single most important part of this AK-47 (in terms of the current laws related to machine guns) is its amnesty registration, which shows the owner’s foresight. Had this not been done, the weapon could have remained undiscovered, its story untold, and ended up under a torch or in a scrap pile along with the many similar firearms we have already lost. Properly registered, this AK-47 is available for individual ownership forever more. ★

Check out this article about Viet Cong Weaponry: 14 Small Arms From the Vietnam War

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below