One of the greatest repeating rifles of all time was introduced to an appreciative market in 1892, when Winchester brought out its brand-new, John-Browning-designed Model 1892 lever gun. Slim, trim, strong and easy handling, the 1892 chambered the same .32-20, .38-40 and .44-40 handgun calibers that Colt was offering in the Peacemaker, making the new design an instant success. Ultimately, over a million were manufactured before being dropped from production at the beginning of World War II.

The story goes that Winchester asked Browning to develop a replacement for the company’s Model 1873. Browning said he’d have a gun to look at in less than 30 days or it would be free. Within two weeks, he had a functional prototype ready to show. The basic design was actually already in existence; Browning scaled down his Model 1886 and adapted it to the smaller calibers. The result was a much stronger action than the 1873’s toggle-link lockup, a fully enclosed frame top that didn’t involve manually manipulating a sliding dust cover and an excellent trail partner to a Colt single-action pistol in a matched caliber. How could that possibly fail?

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

WWII killed off the old Model 1892. However, used domestic samples were still treasured and handed down through the generations. There was a brief fad 40 years ago when good 1892s received a conversion to .357 Magnum. Browning commissioned Miroku in Japan to build versions in both .357 Magnum and .44 Magnum that are still highly regarded today on the used market. Rossi has sold thousands of its Brazilian-made reproductions for decades. Chiappa is selling its Italian clones. The Winchester brand has been reactivated in recent years, with limited manufacture of 1892 variants back at Miroku.

The old 1892 is far from dead, and now Turnbull is offering the best of the best current 1892s in “pre-made” form.

Turnbull Restoration

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Turnbull has built a well-known name for itself doing high-grade restoration work for customers that send in firearms. The company has since expanded into offering limited editions of certain models that are factory new with upgrades that go well beyond what the manufacturers ship out in standard-production form.

Not a full-service custom gunsmith operation in a comprehensive sense of the term, Turnbull’s specialty is wood and steel restoration on certain types of firearms. This involves stripping down a stock and making it “new,” replacing old wood that can’t be salvaged with new period-correct furniture patterns. It also includes cleaning up old well-worn steel surfaces and giving them a showroom shine again.

In general, Turnbull makes Great Grandpa’s old beater into a gun that looks better than it did when it rolled out the factory door 100 years ago. Custom action work, outside-the-box features and exotic modifications are not on the menu. But if you want your old lever gun to look like it came from Winchester when its special-order department was in its prime, this is where you go. And now you can buy a ready-made Winchester classic rifle that rivals anything the original company ever put out in terms of quality and pride of ownership.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The Miroku 1892

Current Winchester lever actions are all made in limited numbers by Miroku for the Winchester brand. Regardless of your opinion of the manufacturing of these U.S. classics outside our borders nowadays, these are the best-made Winchester patterns on the market, bar none. They actually beat out the last years of the old New Haven USRAC plant that closed its doors in 2006, in terms of quality, by a fair margin. The fit and finish are typically very good, and a step above any of the other competing imports.

The decision bring the 1892 back included certain design changes, incorporated into the guns for “safety” reasons. Those include a sliding tang safety, a rebounding hammer and a two-piece firing pin. All of which purists like me dislike because of what they do to the 1892’s operation. The tang safety gets in the way of both the shooter’s thumb and tang sight mounting. The rebounding hammer, intended to prevent an accidental discharge if the rifle’s carried with a loaded chamber, applies much more spring weight.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

That extra springage is necessary to overcome the rebounding function. In the modern Miroku 1892 factory action, the mainspring has to drive the hammer much harder to overcome the resistance at the end of its travel by the lower leg of the hammer/mainspring strut for reliable primer ignition. That leg pushes the hammer back to its at-rest position off the firing pin, and wasn’t there in the original John Browning version that used a half-cock position for safety. This rebounding feature makes for a stiff action and a heavy trigger pull, and was, frankly, not a popular design modification. The Miroku levers can be hard to operate for some shooters, and their triggers are not conducive to accuracy.

Turnbull’s Take

Turnbull starts with a full breakdown of the new 1892s after acquiring them from Winchester, including removing the 20-inch, octagonal barrel from the action. The blued parts that’ll be left blued are set aside. The frame, forend cap, lever, hammer and steel crescent buttplate are all casehardened using a traditional bone-charcoal method, not a more modern (and less expensive) chemical bath process. The same way manufacturers accomplished casehardening in the good old days of long ago. While case colors created by any process can fade over time, the bone-charcoal case-coloring jobs are more durable than the chemical surface colors more commonly used today.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

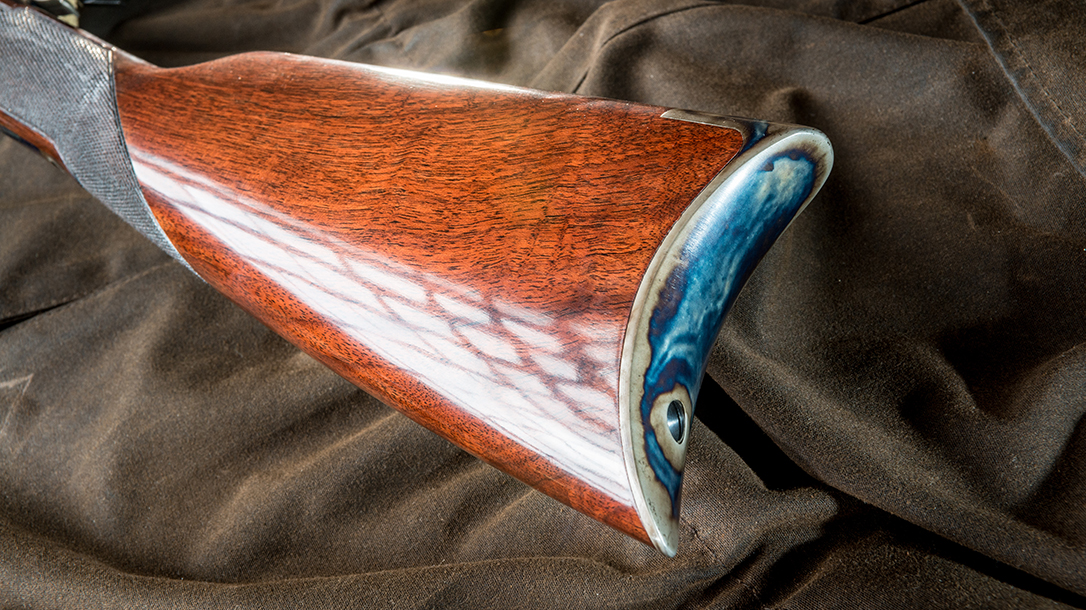

The steel parts get their beauty treatment. Meanwhile, the buttstock and forend see a refinishing with a hand-rubbed oil finish to match Winchester’s classic red shading from the past. This leaves the wood surfaces with a smooth low-gloss look, without the glossy varnish effect found on Brownings. The low-luster finish doesn’t interfere with the fine diamond checkering at the wrist and forend. The result is one strikingly handsome short rifle with a metric ton of bragging points. But things get truly interesting on the inside.

Before the frame gets its casehardening, Turnbull’s craftsmen remove the sliding tang safety. The hole is plugged and welded over, as is the trough in the tang where the thumbpiece slides. The weld is dressed and polished, the top is drilled and tapped for an optional tang sight, and the frame goes on for coloring. The lower leg of the hammer/mainspring strut is also removed, which eliminates the rebounding hammer feature. A steel insert is welded into the hammer to convert it back to John Browning’s half-cock operation before it’s also sent off for casehardening. The current two-piece firing pin is welded into one, and all of the modified parts are polished carefully before reassembly.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

As you can see, Turnbull turns out works of art, but it intends for them to be fully shootable works of art. In my opinion as a diehard traditionalist, this return to the half-cock hammer and the elimination of the tang safety are pretty much worth the price of admission right there.

How It Shoots

On an 82-degree day in June, with my regular 50-yard shooting spot unavailable, I took the Turnbull Model 1892 and six commercial .45 Colt loads to a backup site that had me shooting into the sun on a cloudless day with 10-mph winds behind me. Not the best conditions for accuracy testing with buck and bead sights. After working out the elevation for 50 yards on the rear sight (the third step on the elevator, incidentally), the Winchester pulled off some respectable five-shot groups. I expect those groups to be tighter under better conditions.

Some lever guns can be picky about what they feed, but this 1892 wasn’t one of them. The .45 Colt is an easy-shooting caliber in a rifle, and with the right ammunition, it can be very versatile, too. The gamut runs from plinking fun through competition, hunting and even home defense. This Turnbull beauty can find a place in any of those roles.

Two lead flat-nose (LFN) “cowboy” loads for CAS from Winchester and Black Hills cover the competition role for those who don’t reload, two JHPs for more serious purposes against man or beast from Winchester, and two lead semi-wadcutters (LSWCs) for hunting or defense from Winchester and Federal all fed perfectly, covering a good range of uses for the short rifle. I wasn’t concerned about the JHPs, but LSWCs can induce conniption fits in some actions, but both the Remington and the Federal loads sailed right on through like recycled prairie grass through a buffalo.

The sights consist of a tall brass bead out front and a low buckhorn at the rear, with no white-painted diamond under the rear notch. That popular white diamond seen on many buckhorn-equipped lever guns today is a pet peeve of mine—it’s more of a distraction than shooting aid for me, so I’m glad to see it missing on this rifle. A potential downside for some shooters fine-tuning to a specific load is that the rear buckhorn also omits the small sliding dual-notch plate used for making tiny elevation adjustments. At the typical distances most would be shooting a .45 Colt lever action, I doubt it’ll be much of a handicap, though.

The graceful and stylish crescent buttplate always has immense eye appeal but doesn’t impress my shoulder in heavier calibers. Designed to be held out on the upper arm (as opposed to the usual hollow of the shoulder) when firing, it works for hunting but slows me down for rapid-fire strings and just doesn’t feel right. Between the weight of the rifle at 6 pounds unloaded and the mild thump of the .45 Colt loads, it was tolerable when held in the conventional shoulder spot, but I would not use it there in a .44 Magnum counterpart. Be warned if you’re not already clued in on crescent buttplates.

The only real criticism I had on this rifle was a mild one, but one I’d like to see addressed: The still way-over-sprung action. Turnbull doesn’t alter the unnecessarily strong mainspring when it does its Browning reversion. That leaves a spring designed to counter the rebounding hammer still in place where that much energy is no longer needed. What that does is retain the stiff lever cycling and the heavy trigger pull of the factory setup.

The trigger broke on my test sample at a very clean 6.75 pounds. Clipping about three coils off that mainspring would bring it down a couple pounds without risking ignition failures, while also reducing the amount of effort it takes to cycle the lever. I discussed that with a Turnbull rep; if they don’t start doing that on these guns, it’s easy to do on your own. Again, a mild gripe on a beautifully made rifle.

The Turnbull Model 1892 is available in .45 Colt with a straight wrist (my preference) or in .44 Magnum with a pistol-grip wrist.

These beauties are not cheap at $2,500. However, that merely reflects a premium price for a premium rifle, considering everything that Turnbull puts into them and everything you get out of them. With its rounded frame and compact dimensions, the 1892 is a joy in the hand on foot. It also makes a natural saddle gun. A pleasant shooter for 125 years, it’s one of John Browning’s best designs. There’s a reason all those Hollywood Westerns included 1892 Winchesters wherever they could, and now you can find out for yourself with this high-grade deluxe edition from Turnbull. Once you get one in your hands, you’ll forget all about that price tag.

For more information on the Turnbull Model 1892, visit TurnbullRestoration.com.

Turnbull Model 1892 Specifications

- Caliber: .45 Colt

- Barrel: 20 inches

- OA Length: 37.5 inches

- Weight: 6 pounds (empty)

- Stock: Walnut

- Sights: Bead front, buckhorn rear

- Action: Lever

- Finish: Blued, casehardened

- Capacity: 10+1

- MSRP: $2,500