In warfare, there are a few ways to get behind enemy lines. For centuries the choices were to go around them, which ate up valuable time, resources and money, or go through them, which ultimately cost too much blood. Tacticians looked to the heavens for a better way, and there was one—the paratrooper.

“We used to march them straight into battle, and now we can get 64 guys behind enemy lines with one aircraft instead of three trucks,” said paratrooper and Airborne School instructor U.S. Army Staff Sergeant Matthew Gobble, 1st Battalion, 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment.

- RELATED: Weapons Insider: FN’s Sea deFNder Machine Gun

- RELATED: Guns of the Elite: Legendary 82nd Airborne

The introduction of the paratrooper, a highly trained soldier who falls from the sky, changed the battlefield beginning in World War II. “When you look at a paratrooper, you know he’s hardcore,” said Gobble. “He’s going to be hard-charging, and your logic is, if he’s going to jump out of an airplane into combat, then his fear factor is pretty low.”

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

According to U.S. Army historical documents, the idea to drop soldiers by parachute into combat can be traced back to the U.S. Army’s General Billy Mitchell, who, following the macabre experience of trench warfare in World War I, proposed the idea and demonstrated it at Kelly Field in San Antonio, Texas. The U.S. Army said six soldiers parachuted from a Martin bomber, safely landed and, in less than three minutes after exiting the aircraft, had their weapons assembled and were ready for action on the ground.

Good idea, right? Not to us, not back then. According to U.S. Army documents, the United States officials who attended the demonstration dismissed the idea of paratroopers, although it apparently wasn’t a unanimous decision. The Germans and Soviets, however, were impressed. In fact, the Soviets moved the fastest and had paratroopers as part of military maneuvers as soon as 1930. During the early stages of WWII, the Germans used paratroopers in war so successfully it led to American military forces scrambling to catch up and implementing various stages of paratrooper training programs. As such, May 15, 1942, the U.S. Army Airborne School was officially formed and the United States military has been dropping soldiers via parachute ever since.

Going Airborne

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Today, the U.S. Army’s 1st Battalion, 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment runs the U.S. military’s Basic Airborne Course at Fort Benning, Georgia. The school is three weeks long and combines both officers and enlisted men and women from American and foreign militaries all together in the same basic training program at the same time.

“During jump week, candidates must successfully complete … five jumps from an altitude of 1,250 feet from either a C-130 or C-17 aircraft.”

The first session is known as “ground week,” where students learn the basics of being an airborne soldier. First things first, however, as every student, man or woman, and from any military branch must pass the Army Physical Fitness Test (APFT) for the 17 to 21 age group. According to Gobble, jump school takes its toll on the students mentally and physically, so peak physical fitness is essential for soldiers to make it through the school and be an effective paratrooper back with their units. In addition to being fit, students practice on a mock door, a 34-foot tower and a lateral drift apparatus during ground week. Most students who wash out of jump school do so in the first week due to the high fitness standards or not being able to grasp the training, according to Gobble.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

“Sky diving didn’t prepare me for this,” said Basic Airborne Course student U.S. Army First Lieutenant Sergio Villarreal, a Special Forces candidate required to complete Airborne School before he can continue his quest to wear the U.S. Army’s coveted Green Beret. Villarreal said despite all of the training being the same as far as how to be a paratrooper, going through the program as an officer means it’s a little bit harder because leadership doesn’t stop just because you’re in a student status. “As an officer you are learning how to do something for the first time just like everyone else, but now you’re in charge of it as well. You have to be ready first.”

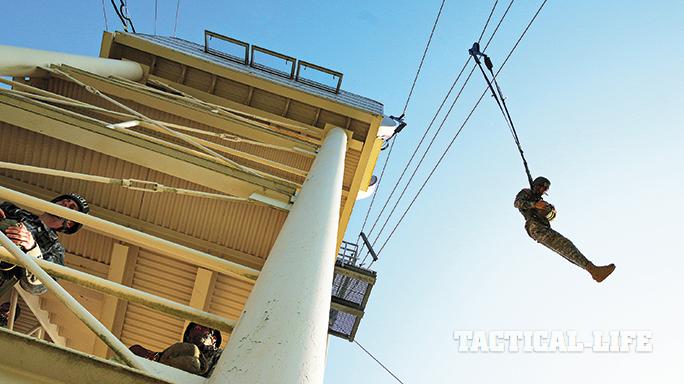

The second week is known as “tower week.” Here jump school candidates must master the Swing Lander Trainer (SLT), mass exit procedures from the 34-foot tower, how to manipulate the parachute from the 250-foot tower and continue to pass all physical training requirements to move on to prime time,

or what is known as “jump week.”

Jump Week

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

During jump week, candidates must successfully complete not one, not two, but five jumps from an altitude of 1,250 feet from either a C-130 or C-17 aircraft. Gobble said a student’s first jump will usually be his or her best jump technically because they’re too scared or nervous not to do exactly as they’ve been trained. “The first and last jumps the students make are their most dangerous,” said Gobble. “The first because they’ve never done it before and their last jump because they’re cocky,” said Gobble.

Villarreal said the last jump was the hardest for him. “Our last jump is done with a combat load, which is about 90 pounds, and it’s awkward,” he said. “On my first jump I was just glad my parachute opened and I concentrated on the basics of getting out of the plane.”

Ideal paratrooper candidates, according to Gobble, are people who pay attention to detail, learn from their mistakes and absolutely want to be here. “If you don’t want to be here it will show, and fast,” said Gobble.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The last known conventional use of paratroopers occurred in January 2013 when 250 French paratroopers from the French army’s 11th Parachute Brigade jumped into northern Mali to capture the city of Timbuktu. And, thanks to the U.S. Army’s Airborne Course, our warriors are ready to come charging from the skies at a moment’s notice if needed as well.