It is undeniable that the semi-auto pistol dominates the self-defense market today, and justifiably so. Technological and tactical improvements have produced a product that is well suited to serving its owner as a primary reactive tool to save his or her hide. But there remain literally millions of revolvers—double-action (DA) and single-action (SA)—in the homes of gun owners today. Many are classic Old West Wheel guns. Are these guns mere paperweights?

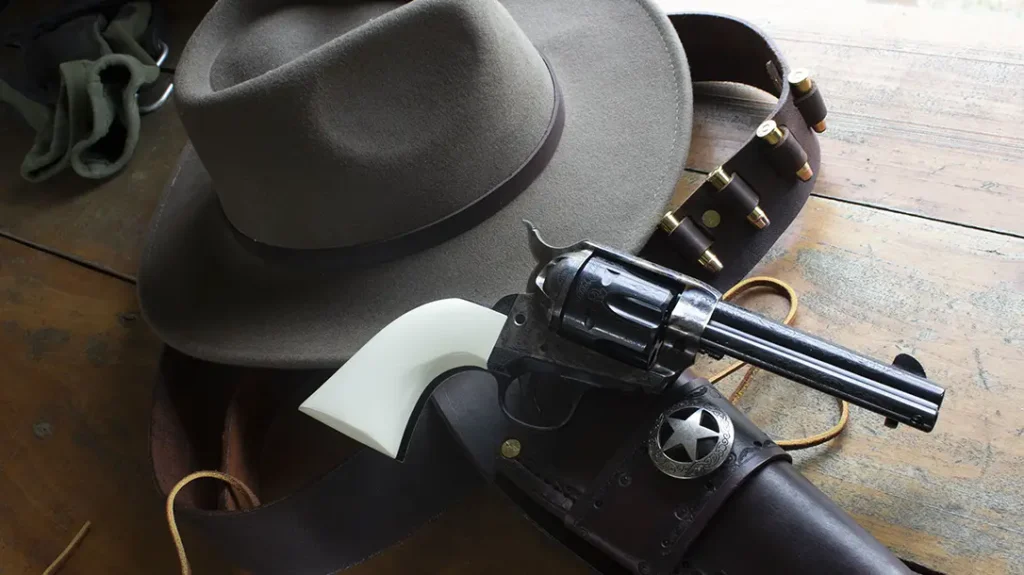

Self-Defense With an Old West Wheel Gun

Single-action revolvers, a.k.a. cowboy revolvers, have been around for over 140 years. Its popularity among gun owners continues to be very strong. Colt has tried many times to retire its iconic Single Action Army, yet the demand for these old “thumb-busters” keeps prodding the company to continue manufacturing them. And once Ruger introduced its Blackhawk single action, it has never looked back. When choosing a self-defense pistol, should single-action cowboy revolvers be dismissed out of hand? I would say no, and here’s why.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Single-Action Revolver Pros

The first advantage of cowboy revolvers is power. The solid, heavy frame of a single-action revolver can contain and control more power than most semi-auto pistols. In many urban environments that can be problematic, since overpenetration in an apartment can be dangerous to innocents, but out in rural areas that power can be effectively used to overcome barriers and longer ranges. I am a staunch supporter of large chunks of lead launched at as high a velocity as I can handle in a handgun. A 250- to 300-grain semi-wadcutter at 1,100 fps or so has measurably more range and terminal effectiveness than a 120- to 180-grain jacketed hollow point (JHP) at 950 to 1,000 fps.

The second single-action advantage is simplicity. A Old West Wheel Guns / single-action revolver is easier and simpler to operate than a semi-auto. There are no safeties—passive or active—to manipulate. Simply cock the hammer and pull the trigger. It could be argued that a DA revolver is even simpler—all that is necessary is to pull the trigger—but that doesn’t take anything away from the thumb-buster.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Improving Efficiency

I am not attempting to argue a case for the superiority of the Old West Wheel Guns / single-action revolver over the semi-auto. For multiple threats, go-fast guns are undeniably better. Also, most semi-autos are easier to conceal than single-actions. But those of us with an affinity toward the single-action are far from under-armed when we choose our otherwise antiquated design. Here are a few ways to make this revolver a bit more efficient as a self-defense pistol.

Naturally, it all begins with the presentation. You will, of course, be shooting two-handed whenever possible. The major difference between what you may already be doing with a semi-auto or a revolver is that the thumb of the support hand will have the additional duty of cocking the single-action revolver.

If you have been shooting single-actions for some time, this may seem a bit strange. However, a few minutes with an empty gun on the range will demonstrate clearly that when you use the strong-side thumb to cock the revolver, it becomes a more complicated operation. Unless you have hands the size of an outfielder’s glove, you will have to move the grip of the revolver in your hand to reach the hammer spur and then move the gun back to a comfortable shooting position. By using your strong-side hand to firmly control the revolver in the firing position, the support hand will be in a more natural position to simply raise that thumb and cock the hammer.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

An additional benefit of using the support hand to operate the hammer means that you can get follow-up shots off more quickly. If you don’t believe me, watch a cowboy-action shooter sometime. Well-practiced shooters can get five aimed shots off in less than three seconds using this two-handed method.

Faster Reloads

The principal difference between single-action cowboy revolvers and more modern firearms is in reloading—both emergency and tactical. If your single-action is a post-’73 Ruger or one altered to utilize a transfer bar, it is safe to charge all six chambers. Normally, shooters eject all the empty cases and then recharge them with loaded rounds.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Develop the habit of loading a chamber right after you eject a spent case. It’s a lot faster, and it keeps you in the fight. The Colt and its clones require more attention since they are not safe to carry with all the chambers charged. This is a moot point if you’re in the middle of a fight, but at some point you will holster the revolver, and at that point, you must ensure the hammer is not resting on a live primer. Those of us who have been shooting single-action Colt-style revolvers for some time have learned to load one chamber, skip one and load the remaining four. Bring the hammer back to full-cock and you will always lower it on an empty chamber.

Gunsite

The late Ed Head, an instructor at Gunsite and a master with just about any firearm, once told me of a new wrinkle in loading single-actions. “I had Colt make me up a Single Action Army in .45 ACP,” he said. When I asked him why that chambering, he quickly replied, “Because I have a lot of ammo and brass.” Ed found that the most convenient way to carry spare ammo for that gun is to carry them in a 1911 magazine. That way, when you are ready to reload, you simply thumb a cartridge from the top of the magazine like a Pez candy dispenser and load it directly into the cylinder.

For the rest of us shooting more traditional cartridges, we need to give careful consideration as to how we carry spare ammo. Traditional belt loops look cool but are very inefficient. Putting a half box of ammunition on your belt is a great way to ensure the belt falls off your butt. I know this from personal experience, and it isn’t a pretty sight, especially when the gun belt takes your pants along for the ride. Carry no more than two cylinders full of cartridges on your belt; a leather box that dumps six into your hand from the bottom is quicker and more efficient than loops.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Low-Light Considerations

Most confrontations occur in low light. I have yet to see any Old West Wheel Guns made with a Picatinny accessory rail, so the prudent shooter will learn and develop a number of methods to utilize an auxiliary light. There are several flashlight techniques—offset, cigar, and crossed wrists are the most popular—and no one technique is perfect all the time. Prudent shooters learn to employ all of these depending on the situation.

But here’s a very important caveat to remember: All revolvers have a gap between the cylinder and the rear of the barrel, and all will eject fire, hot gasses, and some burning particles from that gap during firing. If some part of your hand is in that pathway, expect a painful distraction to occur—anything from a stinging concussion to a nasty laceration, depending upon the ferocity of the cartridge. Should you allow your light source to interfere with that path, it’s possible that ricocheting ejecta could end up in an unfortunate location, like your eyes. Practice and train accordingly.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Old West Wheel Guns: Always Ready To Ride

Make no mistake, I am not advocating that we all give up our semi-autos and replace them with the old guns. But I will say this: A Ruger Blackhawk in .44 Special has a more or less permanent home in my truck. And when I’m on my four-wheeler on the back of my property or aboard a horse playing trail bum on some lonely piece of desert, most of the time there is another .44 or a .45 Colt single-action dangling from my belt. My intent may be for some simple backcountry loafing, but it would be a mistake to “tread on me.”

This post was updated on Feb. 28, 2026.