Bill inwardly smiled at the hand he was being dealt. He already had two pairs: aces and eights. Things were going well for him, even though for the first time in years he had his back to the door instead of facing it. He didn’t expect he would need the derringer he kept hidden in his boot.

That was until Jack McCall walked up behind him and put a bullet through the back of his head. Thus ended the short but storied life of James Butler Hickock, better known as Wild Bill.

Violent Times

Life in the expanding American West could be very violent. Open carry was a common practice on the range and in towns, at least until the 1870s. Concealed carry was also common as well.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The period following the Civil War was an era of great innovation by gunsmiths across the country. The demand and need for small, concealable handguns grew, both as backup and primary defensive weapons. The call for easily concealable handguns in the expanding Western frontier by men and women alike provided a large market for the creative gunsmiths of the day.

It was also a period of changing technologies. The blackpowder and percussion caps that were common during the Civil War and initial westward expansion were giving way to pre-made metallic cartridges and smokeless powder. The old standard calibers of .40, 41 and .45 were being augmented by smaller calibers in .22, .25, .32 and .38.

To survive in an environment where things could go from calm to hazardous in a matter of seconds, people would always carry some form of protection. Most of the time, that meant a small handgun in any of the common calibers of the day, from .22 to .45.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Pocket Pistols

Pocket pistols were smaller versions of standard revolvers that folks could carry in their pockets. They carried either in their pants or more commonly in a jacket or coat. The barrel and grip would typically be shortened, with the former performing well enough for use at short ranges.

Pocket pistols were commonly carried by average citizens, maybe a storekeeper or someone who had to deal with the more unsavory members of society. Carried in an outer pocket, this type of gun was readily available if needed but not obvious due to its small size; this was the first concealed carry. Before gunsmiths actually started producing these pocket pistols, they were made by cutting down the barrels and grips on existing full-sized revolvers.

Derringers

The next evolutionary step came when Henry Deringer (note the single “R”) of Philadelphia developed a smaller handgun that was easier to conceal. His original design was a single-shot pistol in .41 Short. With its intended use as a defensive weapon to stop a bad situation before it became worse, it didn’t need to provide multiple shots—just the one to allow its user to “break contact” and get to safety.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Because of its small size and ease of concealment, it became very popular in the East by gentlemen who felt the need for small defensive handguns. It was also well liked by women who wanted an easily concealable gun that could fit in a fur muff, handbag or elsewhere. Out West, they filled the need of professional gamblers of the day and gunfighters who needed a backup gun. It was easy to employ from its hidden location in a boot top or vest pocket.

Deringer’s design was so popular, however, that it soon became copied and enhanced by dozens of other gun-makers. These gun-makers sold their guns as “derringers,” with two “Rs” in the middle of the name to avoid copyright infringement.

Without a doubt, the most successful of these new designs was Remington’s double-barreled derringer. It featured an over/under design that provided two shots instead of just one. An estimated 150,000 were produced between 1866 and 1935.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Pepperboxes

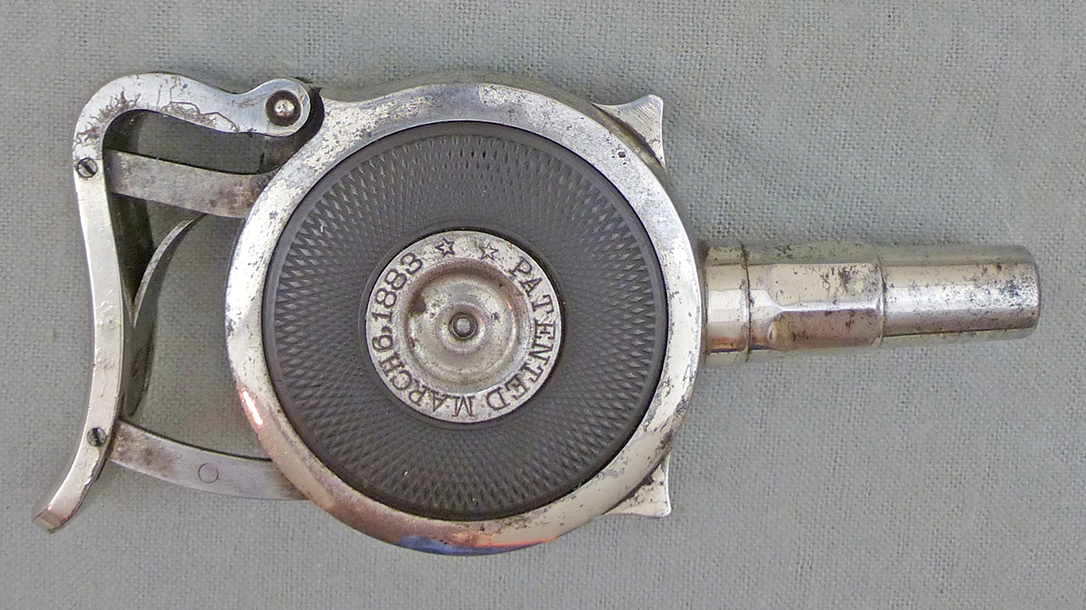

With a history that extends all the way back into the 1500s, the pepperbox (or pepperpot) last came into popularity in the late 1800s when it became a favorite concealed-carry gun of lawmen, gamblers and anyone else who needed a hidden backup. The reason for its popularity was that it was small and easily concealable. But with its multiple barrels, you had more than just the one or two shots provided by a derringer.

The pepperbox was a small handgun very similar to a modern-day revolver, except that instead of a rotating cylinder that fired through a single fixed barrel, the pepperbox had several barrels that rotated around a common axis. When fired, it was like shooting straight from an extra-long cylinder.

Although easily concealed with multiple shots at the ready, the pepperbox did have its drawbacks, including the fact that it wasn’t very accurate due to movement of the barrels. In fact, during this era, Mark Twain said, “The safest place to be when facing a Pepperbox-wielding antagonist was standing directly in front of him.”

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Gun Canes

Originally designed for use by the upper class in metropolises like Chicago or Kansas City, the cane or walking stick became a popular platform for concealing a weapon of some kind. Sword canes were already in use in both Europe and the U.S. Remington came out with a gun cane in 1866. Hiding a .22- or .32-caliber, single-shot, percussion-cap gun that used the cane as its barrel, it would fire either a bullet or shot. Other variants from competing European gun-makers came in .410 gauge or fired pistol cartridges in .40 caliber and 5mm.

Another popular design was to integrate a pistol into the handle of the cane. The handle could be removed from the cane with a twist of the hand to reveal either a knife or spike, a single-shot or pepperbox pistol, or a combination of both. This design was made by many different gunsmiths,

as it was a popular customization request.

Daggers & Razors

Most women of the period, especially those working in saloons of the day, would carry a small pistol or derringer either in a garter belt or hidden in their bosom. But for some, a gun was not a good choice, so they would carry either a small dagger, sometimes dressed up with small jewels. A switchblade was also a popular defensive accessory as it was very easy to conceal, easy to obtain and very effective to fend off the attacks of overly amorous cowboys when the need arose.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Gun Laws

Depending on who you ask, gun-control and concealed-carry laws in the Old West were either more strict or more lenient than they are today. Certainly, they were created to deal with a different set of problems than we face today. Rather than trying to protect society from folks with mental health issues or criminal intent, the laws in the Old West were put in place to help keep cowboys who might get too boisterous when they came into town or range riders with little respect for the standards of “proper society” from settling their disagreements with the business end of a barrel.

The main purpose of gun-control laws that were in place in the 1870s was not to prohibit their ownership, but to keep them out of the hands of people while they were in town. You were required to check your guns at the local sheriff’s office, the major hotel or the stables on the outskirts of town where you left your horse. You could pick them up on your way out of town. But you couldn’t have them with you where there might be gunplay as a result of too much whiskey and not enough skill at cards or dice.

Concealed Weapons Then & Now

As you can see, concealed carry isn’t a new concept. It was a common practice in the Wild West. People back then had a wide variety of choices, just as we do today. The compacts and subcompacts of the day were the pocket pistol and derringer. Today’s carry gun in an ankle holster has replaced their derringer tucked in a boot top, and pepperboxes in a coat pocket have been replaced by in-the-waistband holsters and semi-autos.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

This article was originally published in the spring 2018 issue of “Guns of the Old West.” To order a copy and subscribe, visit outdoorgroupstore.com.