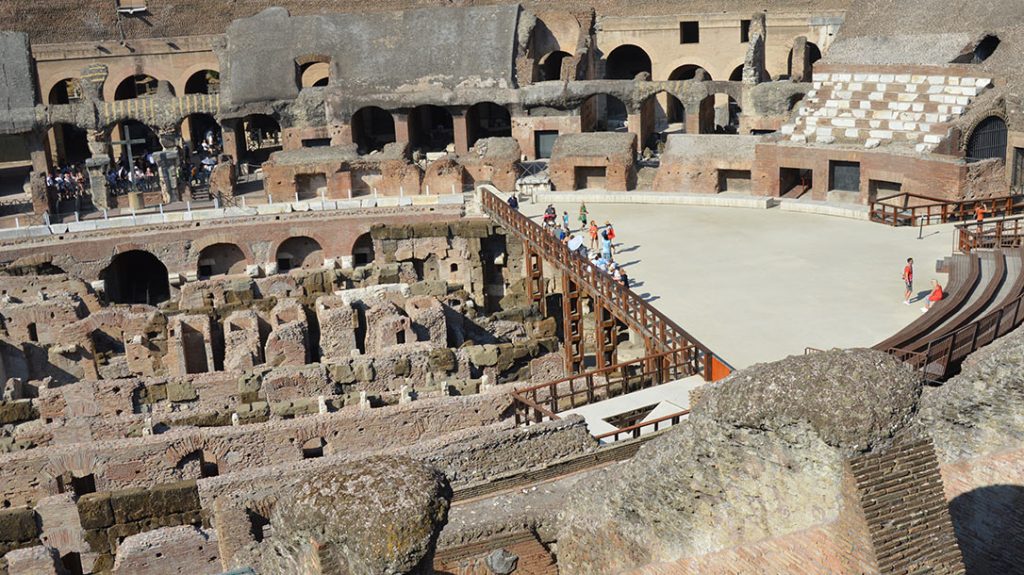

Have you ever wondered why there’s a maze of passageways in the Colosseum’s arena instead of a floor? It’s because you’re looking at the Colosseum’s hypogeum. The wooden floor burned and rotted away in antiquity, and those passageways are essentially the backstage of the Colosseum of Rome. Though in this case, it would be more accurate to call them the understage. The hypogeum was a major step forward in arena design that allowed theatrical versatility impossible with a solid floor arena.

Inside the Colosseum of Rome With The Real Gladiators

During an unexpected trip to Rome last July, I finally got a tour of the hypogeum. This is thanks to the efforts of my friend Stefan Matiu who operates Explore Italy Tours. He managed it despite my lack of pre-planning, Covid-19 restrictions, and a surprise suspension of ticket sales due to a European Union G-20 summit. You can only tour the hypogeum with a guide.

Stefan pulled a few strings to add me to one of his group tours. Additionally, he shared with me his historical analysis of the great Roman Colosseum. I wish I had the space to include it all in this story. If you plan to be in Rome, contact him to book a tour, and you’ll get to hear of the Colosseum yourself. The cost of a quality small group tour is well worth it.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

From an engineering standpoint, the Colosseum’s hypogeum was amazingly sophisticated. Before a show, its cramped spaces were filled with the massive wooden machinery to operate 60 elevators and trap doors. Not to mention waiting gladiators, caged wild animals, theatrical scenery, and the arena staff (mostly slaves).

All labored to coordinate the entrance of each element of the spectacle at the appropriate time and place by lamp light in stagnant air heavy with the stench of sweat, blood, urine, and feces.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Today, the passages are bathed in sunlight except for a small portion covered by a reproduction floor on the East end of the arena. It’s easy to forget the hypogeum would never meet modern OSHA safety standards. While not as deadly as the arena, it was an extremely dangerous place to be. A little background of the Colosseum and the Roman games will help put the significance of the hypogeum in perspective.

Enter The Arena

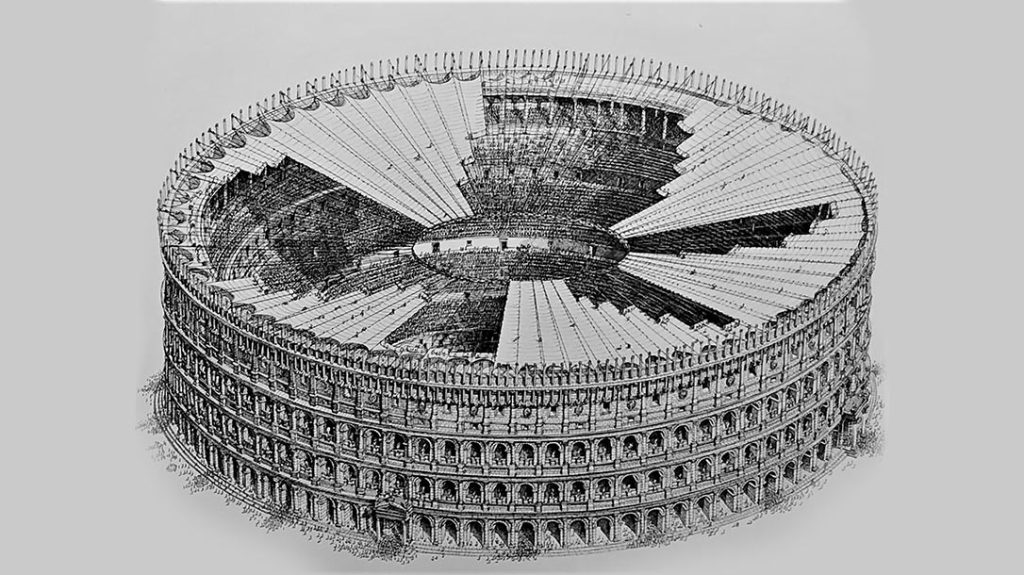

The Colosseum of Rome, originally known as the Flavian Amphitheater, was the largest arena in the ancient world. It first opened to the Roman public unfinished 1,940 years ago. Its oval footprint is 620 x 513 feet with 80 arched entrances. Two of these entrances were reserved for the emperor and two for the participants of the varied spectacles to depart, alive or dead. (There’s a reason those arches are big enough to drive a herd of elephants through.)

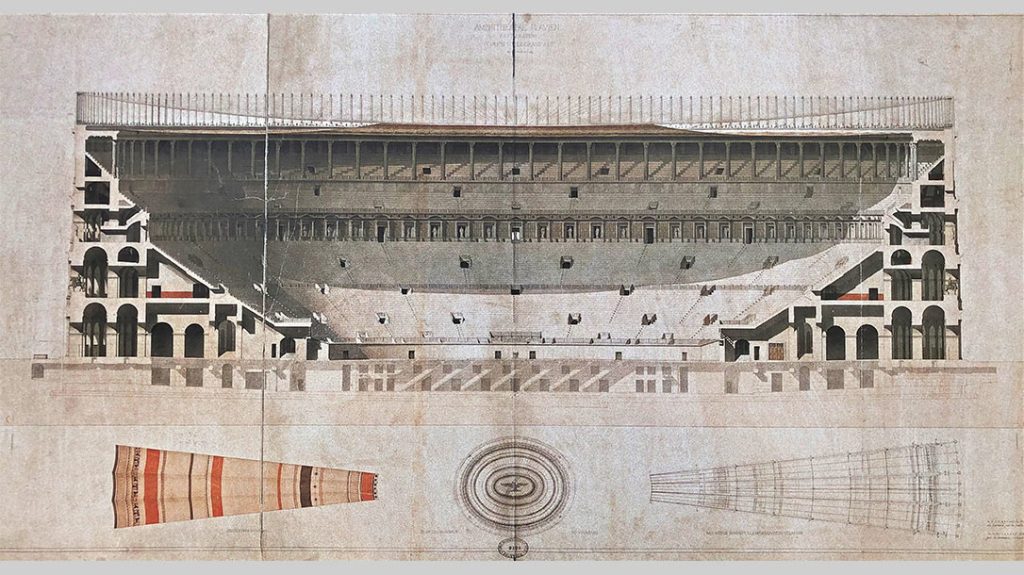

When completed, it stood 159 feet high with five tiers of seating. Based on social class, the closest seats to the 272 x163 foot oval arena were reserved for senators and distinguished men (patricians). The highest tier was for women and slaves. I am tempted to call the highest tier the cheap seats. But the fact is admission to the games was free to all Romans.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

With an estimated capacity of around 50,000 spectators (some researchers think adding a standing crowd could boost that to 70,000), it was the largest and most advanced arena of its time. It was built from the outset to host gladiatorial combats, wild beast hunts, and other bloody public spectacles that were extremely popular entertainments at the time.

It remained in use as a blood sports venue for about 440 years (until 523 A.D.). However, gladiator duels were banned in 438 A.D. by Emperor Valentinian III.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Legacy Building

Construction began in 70 A.D. by order of Emperor Vespasian, the first of the Flavian family to rule the Roman Empire. It took more than a decade to complete, and Vespasian died before the grand opening. Vespasian’s sons, Titus and Domitian, followed him in succession and completed the magnificent amphitheater that bore their surname. Except, it doesn’t.

If you are trying to build a legacy for yourself and your imperial lineage through public architecture, there’s a cautionary tale about how the Flavian Amphitheater came to be called the Colosseum.

The short version is you don’t put a colossal 98-foot-tall gold-plated statue of a dude in front of it. That seems pretty obvious now. But Vespasian was stingy by nature and couldn’t see scrapping a perfectly good giant statue. Even though it had the face of an extremely unpopular previous emperor who had nearly bankrupted Rome building his outlandish personal palace.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The statue previously stood in the giant vestibule of the infamous Nero’s Domus Aurea (literally Golden House). Much of the Colosseum was built on private property Nero appropriated from the citizens of Rome. Vespasian tore down half of the Domus Aurea, filled in Nero’s private artificial lake, and built the new amphitheater over it to restore the land to the Roman people.

Vespasian recycled Nero’s flatteringly and unrealistically buff giant statue of himself by adding a rayed crown (like on the Statue of Liberty). This changed it to a representation of the Roman god of the sun. By the 10th century, and probably much earlier, the Flavian Amphitheater was being called the Colosseum.

100 Days of Games

Vespasian’s frugality helped get Rome back on the road to financial stability. Likewise, his son Titus, an able general, really helped cash-flow by sacking Jerusalem. The rich plunder from this war funded much more than the new amphitheater.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

When Titus took the throne in 79 A.D., the empire was hit with a series of disasters (complete destruction of the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, plague, and earthquake).

After those trials, with money in the treasury, Titus probably felt people were ready to let the good times roll. Even though the Flavian amphitheater wasn’t quite done. In 80 A.D., before the top two tiers were finished, Titus inaugurated it with 100 days of games.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The “games” were called Menura by the ancient Romans. This Latin word refers to gifts or obligations the high classes of Roman society (patricians) owed to ordinary citizens (plebians).

In Rome, the editor (sponsor) of the Menura paid for everything as a public obligation. Often this was the emperor himself. Because events were outrageously expensive to put on, they were actually rather few in number. In a normal year, the Roman Colosseum might have been the scene of five or six Menura lasting only a few days. Most of the time, it stood empty and unused.

Let The Games Begin

We don’t know the precise schedule of events during the inaugural games, but scholars do know the general pattern they took around the empire. In the morning, the events focused on animal acts. The Ventores were professional hunters and fought with various weapons, alone or in groups, against one or many animals.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The Bestiarii were another class of animal fighters. They were usually unarmed or with just a staff and used acrobatic skills to evade attacking animals. Animals also fought each other.

To reduce the chances of dangerous animals escaping into the audience, nets with rollers on top were hung above the edge of the arena, and guards armed with bows were on alert for emergencies. During Titus’ games, it was recorded that around 9,000 beasts, wild and tame, were slain in the arena.

At midday, spectators watched public executions of condemned criminals, military deserters, prisoners of war, and eventually, though this is still a subject of debate among scholars, some early Christians.

The most popular executions involved the condemned being killed by wild beasts. Lions, leopards, and bears tearing apart the condemned were real crowd pleasers, as was trampling by elephants or buffalo.

Lacking these exotic creatures, which had to be captured and transported at great expense from the far-flung edges of the empire, wild dogs would be substituted with the victim being draped in freshly skinned animal hides.

Stepping Up the Drama

To step up the drama of executions and possibly reinforce an important moral lesson, costumes, props, and sets were used to theatrically recreate the fatal moments of well-known stories from plays, Roman religious mythology, or battles.

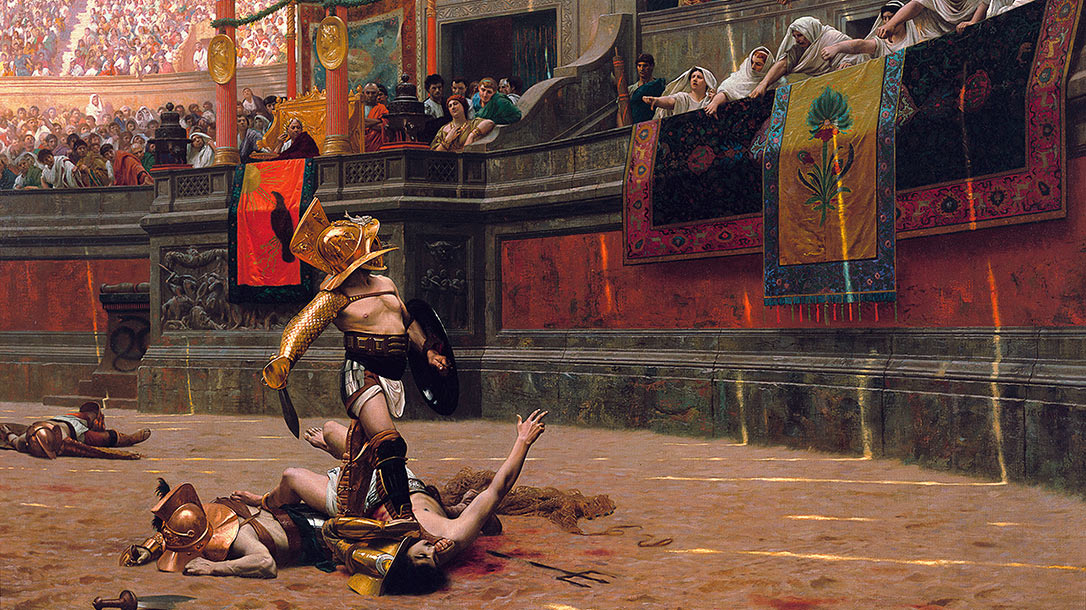

The afternoon was devoted to gladiatorial combats. Following very strict rules and strenuously referred, these always potentially lethal battles were fought between two or more highly trained slaves who were expected to maintain professional dignity, fight, and possibly die with honor.

Few citizens or freedmen chose the profession because to do so amounted to voluntary enslavement. In Roman culture, strength, courage, discipline, honor, endurance, and martial skill were paramount manly virtues. As such, gladiators were uniquely positioned to become grand popular heroes.

Quite a number did, earning their freedom and some even amassing a personal fortune on the way. Under normal circumstances, this could take quite some time. Research suggests the typical gladiator fought in only two duels a year. Correspondingly, only one in 10 duels ended in death.

Below The Scenes

While all the previously described butchery was unfolding on the arena floor, hundreds of slave “stagehands” toiled in the hypogeum below to create the surprise, suspense, and what we would now call “movie magic” to increase the theatrical appeal of the games. Consider what it might have taken to get a single lion to suddenly pop up in the arena.

In the planning of the games, the equivalent of stage managers worked out all the human and equipment resource allocation. Not to mention timing and communication requirements to get the lion in the arena at the right time and place.

Keep in mind that long before the show, a trainer prepared the recently captured lion, not normally inclined to attack and eat men, to be extremely aggressive toward them. The “trained” lion had to be transported to the Colosseum of Rome. There it was guided underground into a tiny, caged-off alcove, barely big enough to contain it.

I imagine that was similar to trying to get a house cat into a pet carrier. But the cat weighs 400 pounds and hates you. During Titus’ games, we’ll assume 90 animals were killed each day. This required the slaves who stocked the hypogeum with wild beasts to do this risky task 90 times a day.

All the animals weren’t predators, of course. However, they were all agitated and angry and as dangerous as they were ever likely to be. Any mistakes made in handling the animals could have fatal results.

Releasing the Animals

At show time, in proper turn, we’d expect the slave animal handlers to somehow release the lion from its cage and guide it to the right position under the arena floor for release.

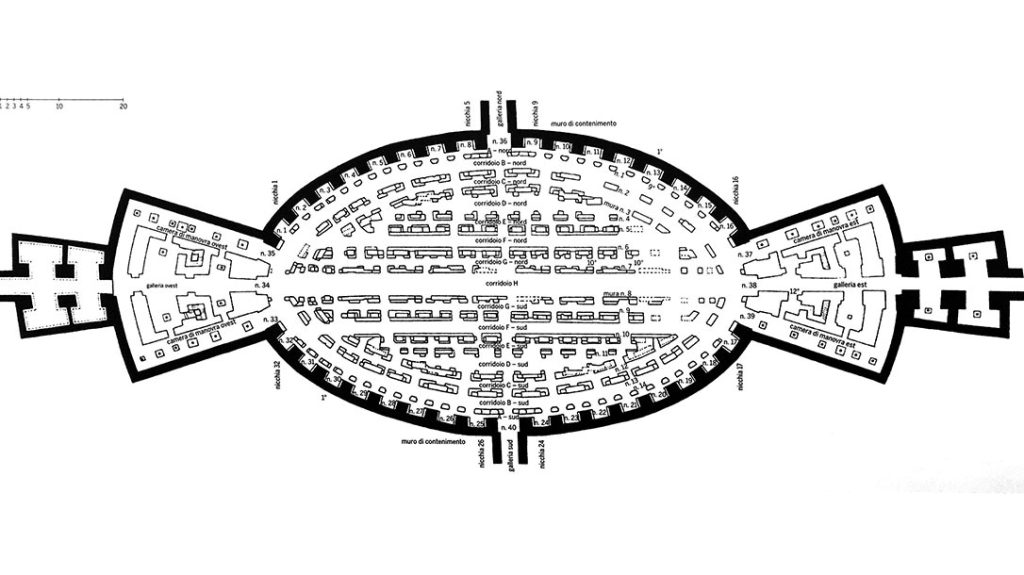

Let’s presume the lion was in the upper level of double-decker caged alcoves around the perimeter of the hypogeum (Corridor A on the map). If the lion’s release was to be on the rim of the arena directly above, that might have been as simple as installing a ramp from the cage to the trapdoor. Then simultaneously open the cage and trapdoor when the signal comes.

We would expect the lion to instinctively run toward freedom. If the lion needed to appear some distance from its cage, scholars speculate it was transferred to a portable wooden cage and moved to the appropriate lift.

Impressively Complex Mechanical Apparatus

The mechanical apparatus used to get anything onstage from the hypogeum were impressively complex. Likewise, they must have required a great deal of training to operate efficiently.

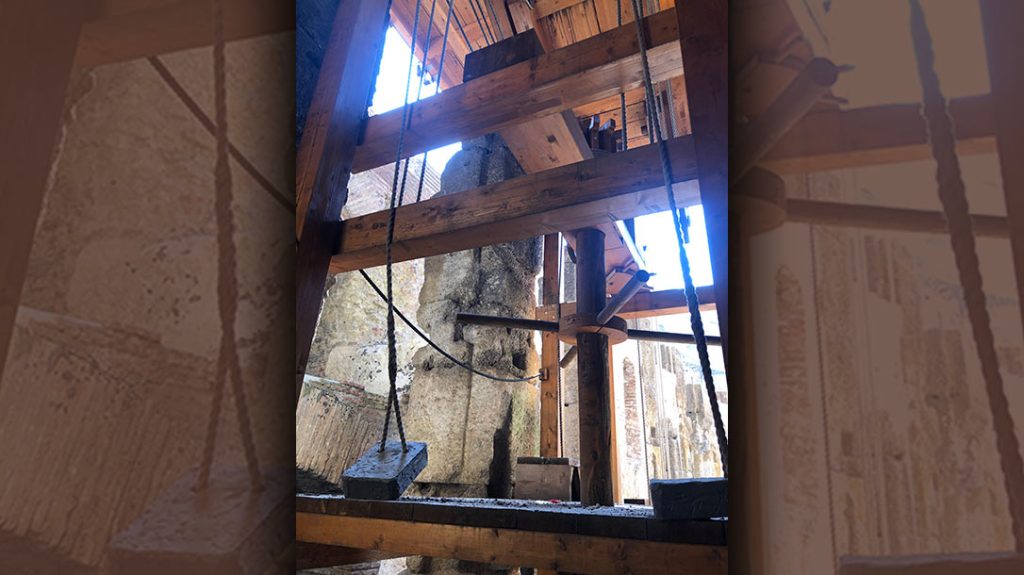

Based on careful research, a reproduction of one of the hypogeum’s 60 lifts was built in situ. Slaves quickly orbiting the central axis of the double-decker capstans pushed the handles around and around. This raised the big counterweights needed to abruptly open the trap doors in the arena floor and propel the lifts upward through the openings…causing the lion to seemingly spring from nowhere.

An operation like this relies on lots of strong ropes and pulleys. These would have to be constantly inspected and maintained in the moist underground environment. Working the hypogeum’s stagecraft machinery and controls was probably like handling the rigging of a clipper ship sailing at night. Each slave had to know what each rope and lever did, where it was, and how to operate it. All in the stifling darkness while waiting for his cue.

The hypogeum had to be a noisy place with the heavy footfalls of gladiators in mortal combat. Not to mention the shouts of tens of thousands of spectators above combined with the growls and roars of animals. Add to that the creaking machines and ropes and the grunts of laboring men below.

Ruins And Ruminations

All that remains of the original hypogeum lifts are the bronze bushings for the capstans in the corridor floors and the slanting grooves cut into the walls that were tracks for large platforms used to hoist scenery up or down as needed.

The Colosseum spectacles wowed their audiences with never-before-seen stagecraft that warranted being written down. That’s how we know about it today. The engineering, planning and coordination that made it possible required organizational skills that are best described as simply…Roman.