The 1929 St. Valentine’s Day Massacre in Chicago is one of the most well-known crimes of the 20th century. It has it all: Al Capone, Bugs Moran, illegal alcohol, a gang war, and, of course, Tommy guns.

Guns of the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre

What is less-known, however, is the story of how these guns used in a crime in Chicago, Illinois, ended up in St. Joseph, Michigan, and how a fender-bender led to their recovery and the downfall of one of the most wanted men in America.

The Massacre

On February 14, 1929, a group of men from the South Side Gang were gathered in a garage owned by George “Bugs” Moran. The men were unloading a shipment of liquor when they were surprised by a group of local police. The officers ordered the men to line up against a brick wall, presumably to be searched, cuffed, stuffed into a car, and whisked away to the local police station for booking. Or, if they were lucky, these officers would be on the take and could easily be dispatched with some cash and, perhaps, a case of the illegal hooch.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Instead, the officers turned out to be imposters. They were members of Al Capone’s North Side Gang, sent to take out Moran. These “officers” watched as two other well-dressed men entered the garage, produced an array of weapons, including two Thompson submachine guns, and killed the seven men from Moran’s gang as they stood against the wall. With the deed done, the guns were handed to the “police” and they escorted the shooters outside to a waiting phony police car, acting as if they had arrested the men.

Bodies Riddled With Bullets

Six of the victims died instantly, each man averaging more than a dozen bullet holes in them; one victim – Frank Gusenburg – lingered for a few hours, despite having been shot a staggering 22 times. When asked who shot him, he remained a loyal gangster, refusing to give any details. “No one shot me,” he replied.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

Approximately 70 shots were fired from the two Thompsons in the garage. A couple shotgun blasts rounded out the carnage.

A number of men were suspected of being involved in the crime. Despite numerous eyewitness reports of what happened and rigorous questioning of some suspects, there wasn’t sufficient evidence to bring anyone up on charges.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

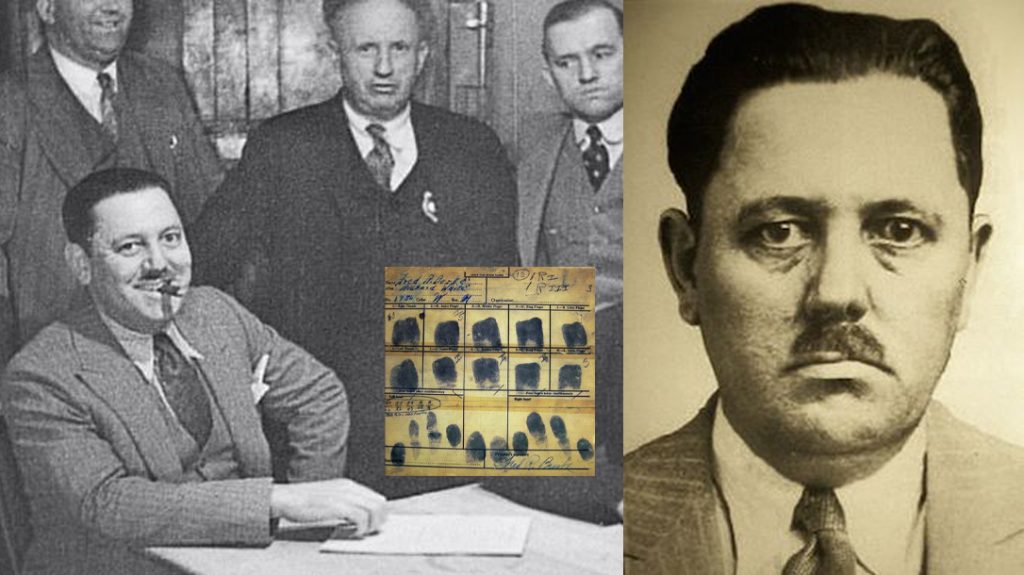

Fred “Killer” Burke is one of the gangsters who was suspected of being a gunman in the garage. But just like the others, there wasn’t enough evidence to try him for the crime. The case went cold until Burke slipped up later that year.

Fateful Fender-Bender

On the evening of December 14, 1929, Fred Burke was headed to the local train station in St. Joseph, Michigan, to pick up his wife, Viola Dane. While en route, he was involved in a fender-bender with Mr. Forrest Kool. Upon exiting their cars to examine the damage, Kool could smell alcohol on Burke, who said he’d compensate Kool for the necessary repairs. Burke produced a wallet full of large bills – far larger than the repairs would cost – so Kool agreed to follow him into town where one of the bills could be broken.

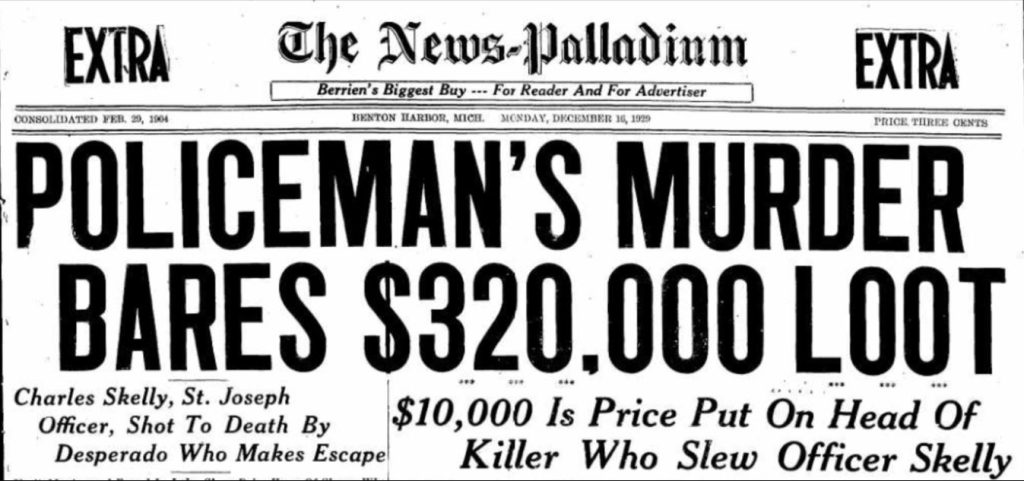

While traveling to town, Burke took off and managed to lose Kool. Flustered, Kool got the attention of Patrolman Charles Skalay, a 25-year-old officer who had been on the job for just seven months. (Charles’ family “Americanized” the name to “Skelly” upon their arrival.)

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

As Mr. Kool described the car and driver from the accident, Fred Burke just so happened to drive through the intersection where the victim and the officer were conversing. Patrolman Skelly hopped on Kool’s running board and they pursued Burke.

When they caught up with drunk gangster, Skelly approached his car and told him that they needed to talk. Burke produced a Colt 1911 pistol and fired three times, killing the young officer.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

The Smoking Guns …

Burke sped off, but he soon wrecked the car, fled on foot, and managed to escaped capture. Exactly who killed Skelly was unclear at the time, but a search of Fred’s car turned up clues as to the suspect’s identity. Papers inside listed his name as Fred Dane, which was one of his many aliases, as well as the address of a bungalow in nearby Stevensville.

Officers showed up to search the home just as Burke’s wife Viola arrived in a cab because Fred never showed up to the train station. While searching an upstairs closet, the officers found a stash of items that would soon be linked back to the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre.

The officers found two Thompson submachine guns with nine drum magazines, three stick magazines, two rifles, one sawed-off shotgun, some pistols and revolvers, more than 5,000 rounds of ammunition for a variety of firearms, tear gas bombs, three bulletproof vests, multiple disguises, more than $390,000 in bonds stolen from a bank in Wisconsin, and some well-worn copies of various detective novels.

Advertisement — Continue Reading Below

A fingerprint lifted from the house matched those on file for Burke, and the search was on for one of the most wanted men in America.

The Birth of Forensic Ballistics

The Thompsons were turned over to Dr. Calvin Goddard in Chicago, where he was pioneering the fledgling field of forensic ballistics. Goddard was an Army officer and the head of the Bureau of Forensic Ballistics, which was the first independent crime lab in the United States.

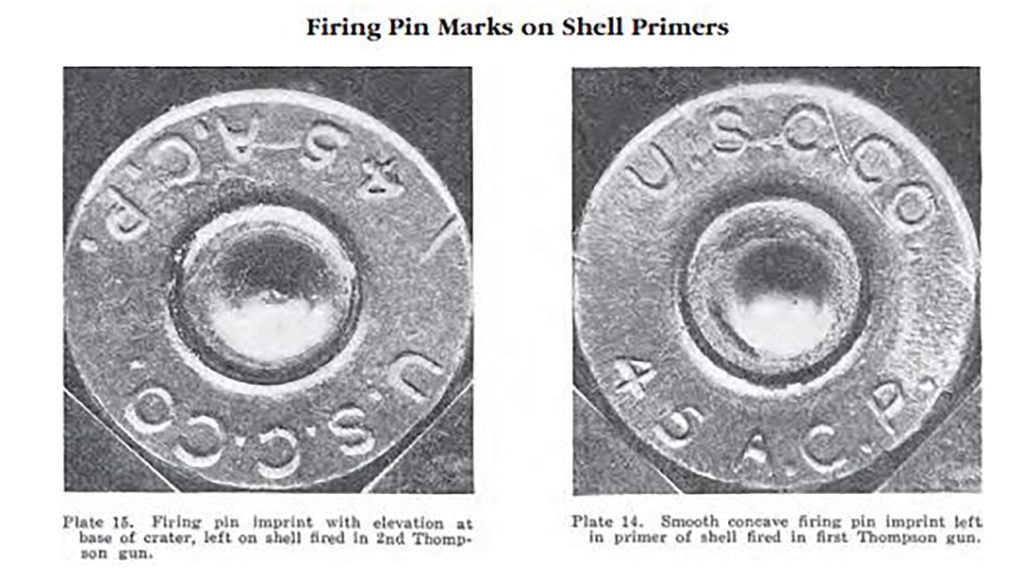

Goddard test fired the guns taken from Burke’s home in order to compare them to the bullets and spent cartridges recovered from the scene of the massacre. Using a microscope to examine the rifling marks on the bullets, the firing pin indentations on the primers, and markings on the cartridge from the extractors, Goddard was able to confirm that the Thompson submachine guns found in Burke’s closet were indeed the ones used on February 14, 1929.

The Tommy Guns

Thompson submachine gun Model of 1921, serial number 2347, was produced by Colt’s Patent Firearms Co. and delivered to Auto-Ordnance between July 18 and 23, 1921. On November 12, 1924, it was sold to Deputy Sheriff Les Farmer of Marion, Illinois. Farmer left his career in law enforcement to become a member of the St. Louis-based gang known as Egan’s Rats. Serial 2347 eventually found its way into the hands of Fred “Killer” Burke sometime before the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre.

The other Tommy gun tested by Goddard was also made by Colt’s Patent Firearms Co. and was also delivered to Auto-Ordnance on January 30 or 31, 1922, as a Model of 1921A. The barrel was later modified with a Cutt’s Compensator, re-designated as a Model of 1921AC, and was sold to Von Frantzius Sporting Goods in Chicago on October 19, 1928. It was one of three Thompsons in the shipment, each accompanied by a drum magazine.

Mr. Von Frantzius sold the gun to Mr. Frank V. Thompson, who requested arrangements be made by Mr. Von Frantzius to have local gunsmith Valentine Guch remove the serial number, which was 7580, from all parts of the gun. Mr. Guch’s work cost an additional two dollars.

The gun was packed in a crate, along with four bricks, and mailed from the sporting goods store to an address belonging to Victor Thompson in Elgin, Illinois. Victor then gave the gun to Frank on October 23, 1928. Serial 7580 was then sold by Frank to Mr. Bozo Shupe of Chicago, who is believed to have been the man who put it into circulation with the gangsters before the massacre.

Gun on the Run

Shupe was questioned by authorities in an effort to find out what happened to the gun. He refused to provide any information and was soon found murdered on Chicago’s West Side.

Because Valentine Guch had removed the serial number from the gun, Calvin Goddard had to find a way to recover any trace elements of it. To do this, he poured acid on the gun in order to raise the etching, traces of which were buried deeper in the gunmetal.

Goddard’s acid method worked. The model and serial number were indeed visible, albeit rather faint, when viewed at the right angle under ideal lighting conditions. Goddard’s goal was to identify the gun by any means necessary; preserving it for the future was not part of his goal, and so the acid he used ate away at the gun’s finish. Evidence of the acid-induced finish loss is still visible on the gun today.

The Jig is Up

Fred Burke moved to Missouri, assumed a new alias, married a woman named Bonnie Porter, and managed to steer clear of the law until March 26, 1931. A man from St. Joseph, Missouri, spotted Burke’s picture in an issue True Detective, which was a true crime magazine, and recognized him as his neighbor Richard White.

Authorities descended upon the residence of “Mr. White” and were able to surprise him while he was asleep. Upon waking, Burke briefly reached for a revolver by his bed before realizing that his attempt was fruitless. Cornered in his bedroom by a group of officers, he surrendered without a fight.

Two days later, on March 28, 1931, Fred Burke was extradited from St. Joseph, Missouri, to St. Joseph, Michigan, where he was held in the Berrien County Jail before facing trial for the murder of Patrolman Skelly.

On April 27, 1931, Burke plead guilty to second degree murder and was sentenced to life in prison. Nine years later, on July 10, 1940, he died of a massive heart attack at the age of 47. Burke went to his grave having never implicated anyone in the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre. He’s buried at the Marquette State Penitentiary under his real name – Thomas A. Camp.

The Evidence Today

Moran’s garage was torn down in 1967. The back wall, still riddled with pockmarks from the massacre, was cataloged and sold to a man who intended to sell the bricks as souvenirs. That idea failed, so they were installed in the men’s room of a Vancouver nightclub as a backdrop for the urinals. When the club closed, the wall was acquired by The Mob Museum in Las Vegas, where it is on permanent display.

Fred Burke’s home in Stevensville, Michigan, still stands. No longer a residence, it is now home to a Coldwell Banker real estate office. The staff working there are well aware of the building’s tie to history’s most infamous mob massacre.

Much of the weapons cache recovered from the bungalow in Stevensville has long since disappeared, falling victim to souvenir hunters and lax law enforcement security. However, the two Thompson submachine guns, serial numbers 2347 and 7580, are still held at the armory of the Berrien County Sheriff’s Department in St. Joseph, Michigan.

The guns are still considered to be evidence in the seven unsolved murders of the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre.

Auto-Ordnance Thompson SBR

The closest you can come today to owning a Tommy Gun like the one used on 2/14/29 is the Thompson made by Auto-Ordnance.

A subsidiary of Kahr, Auto-Ordnance offers a Thompson SBR (short barrel rifle) that is an almost exact replica of the massacre guns. The gun is machined from solid steel and then equipped with a 10.5-inch barrel and a 2-inch compensator. Rounding out the rifle’s iconic appearance is a vertical forward grip with finger grooves, a removable American walnut stock, and the option to use either stick or drum magazines.

Because of current firearm laws, the Auto-Ordnance Thompson SBR is an NFA weapon, requiring special registration and a $200 tax stamp.

For more information, visit auto-ordnance.com.